The story so far

In Part 1, we learned that Impacket's LDAP reconnaissance tools use OID-based filters that get transformed into bitwise operations in Event ID 1644 logs, breaking our string-matching detection rules.

Part 2 revealed how whitespace variations in LDAP filter formatting can cause identical queries to log differently, creating another detection blind spot.

Now, in Part 3, I'm going to share a different kind of story. Not about a problem I was actively investigating, but about something I'd been walking past in my logs for weeks. Something I wasn't even looking at because I was so focused on filters and attributes.

It started the day I finally noticed a field called "SDFlags."

The thing I wasn't looking at

After Parts 1 and 2, I'd been laser-focused on LDAP filters and attributes. I was building detection rules based on filter patterns, tracking which attributes attackers queried, correlating searches. Event 1644 logs were my home.

But I was only looking at specific parts of those logs:

-

Filter field - This is what I analyzed in Part 1

-

Attributes field - This is what mattered for detection rules

-

Visited/Returned entries - For understanding query scope

Then one day, while scrolling through logs, something finally registered in my peripheral vision:

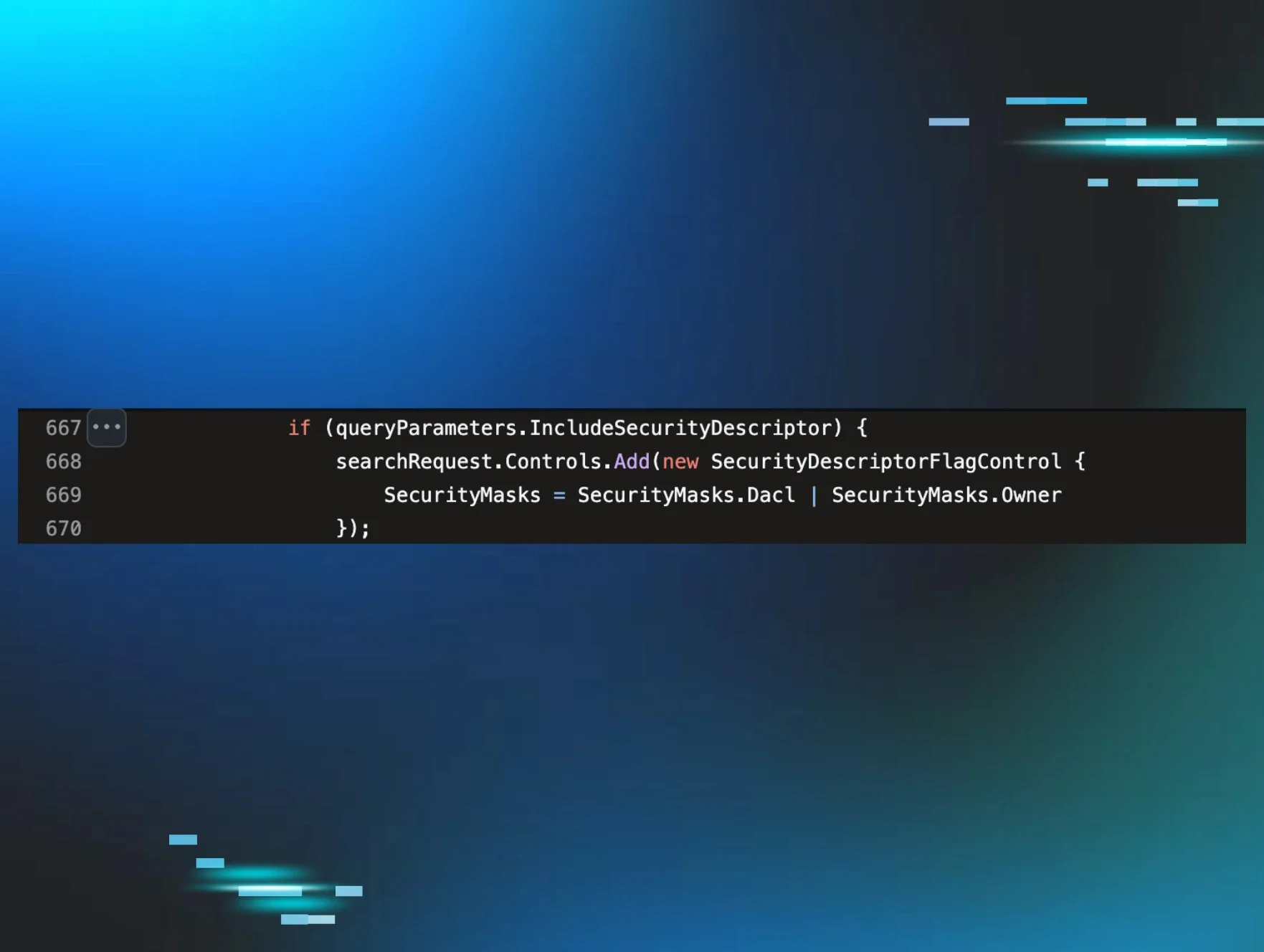

Figure 1: SharpHound group enumeration query captured in Event ID 1644, showing SDFlags:0x5 (Owner + DACL) and the characteristic sAMAccountType filter for all group types.

SDFlags: 0x5

I'd seen this field dozens of times before. But I'd been so focused on the filter and attributes that my brain had just... skipped over it. It was log noise. Extra metadata. Not what I was looking for.

Until the day I actually saw it.

"What is SDFlags?"

The first investigation: When does it appear?

Once I noticed SDFlags, I couldn't unsee it. I started looking for patterns:

# When does SDFlags appear?

Get-WinEvent -FilterHashtable @{

LogName = 'Directory Service'

ID = 1644

StartTime = (Get-Date).AddDays(-7)

} | Where-Object { $_.Message -match 'SDFlags' } |

Measure-Object

# Result: 127 events with SDFlags in the past week

# What attributes are requested when SDFlags appear?

Get-WinEvent -FilterHashtable @{

LogName = 'Directory Service'

ID = 1644

StartTime = (Get-Date).AddDays(-7)

} | Where-Object { $_.Message -match 'SDFlags' } |

ForEach-Object {

if ($_.Message -match "Attribute selection:\s*\r?\n(.+?)\r?\n") {

$matches[1]

}

} | Group-Object | Sort-Object Count -Descending | Select-Object -First 5

# Result: 100% of SDFlags queries include "nTSecurityDescriptor"

Pattern discovered: SDFlags ONLY appears when queries request the nTSecurityDescriptor attribute.

Okay, so SDFlags and nTSecurityDescriptor are connected. But what IS nTSecurityDescriptor? And why should I care?

This was turning into a deeper investigation than I expected.

Following the OID: What is SDFlags?

I took the OID from the "Controls" field and searched: 1.2.840.113556.1.4.801

Microsoft's MS-ADTS specification, Section 3.1.1.3.4.1.11: LDAP_SERVER_SD_FLAGS_OID

From the spec, this control is used to specify which security descriptor information to return.

So it's filtering what data gets returned. But filtering WHAT exactly?

The bitmask values:

-

0x1 = OWNER_SECURITY_INFORMATION

-

0x2 = GROUP_SECURITY_INFORMATION

-

0x4 = DACL_SECURITY_INFORMATION

-

0x8 = SACL_SECURITY_INFORMATION

So 0x5 = 0x1 + 0x4 = Owner + DACL.

Why SDFlags matters: The SACL permission problem

Here's something I didn't understand at first: why do tools need to use SDFlags at all?

The answer is permissions. As FalconForce explains in their SOAPHound blog post, when you query nTSecurityDescriptor without SDFlags, Active Directory tries to return all four components by default (Owner, Group, DACL, and SACL). But most accounts don't have permission to read the SACL.

Here's the catch: when AD can't return all requested components, it returns nothing.

SDFlags solves this by letting you specify exactly which components you want. By requesting only Owner + DACL (0x5) or just DACL (0x4), tools avoid the SACL permission issue and successfully retrieve the security descriptor data.

This is why attack path tools must use SDFlags. Without it, the queries fail silently for non-privileged accounts.

Down the rabbit hole: What even is nTSecurityDescriptor?

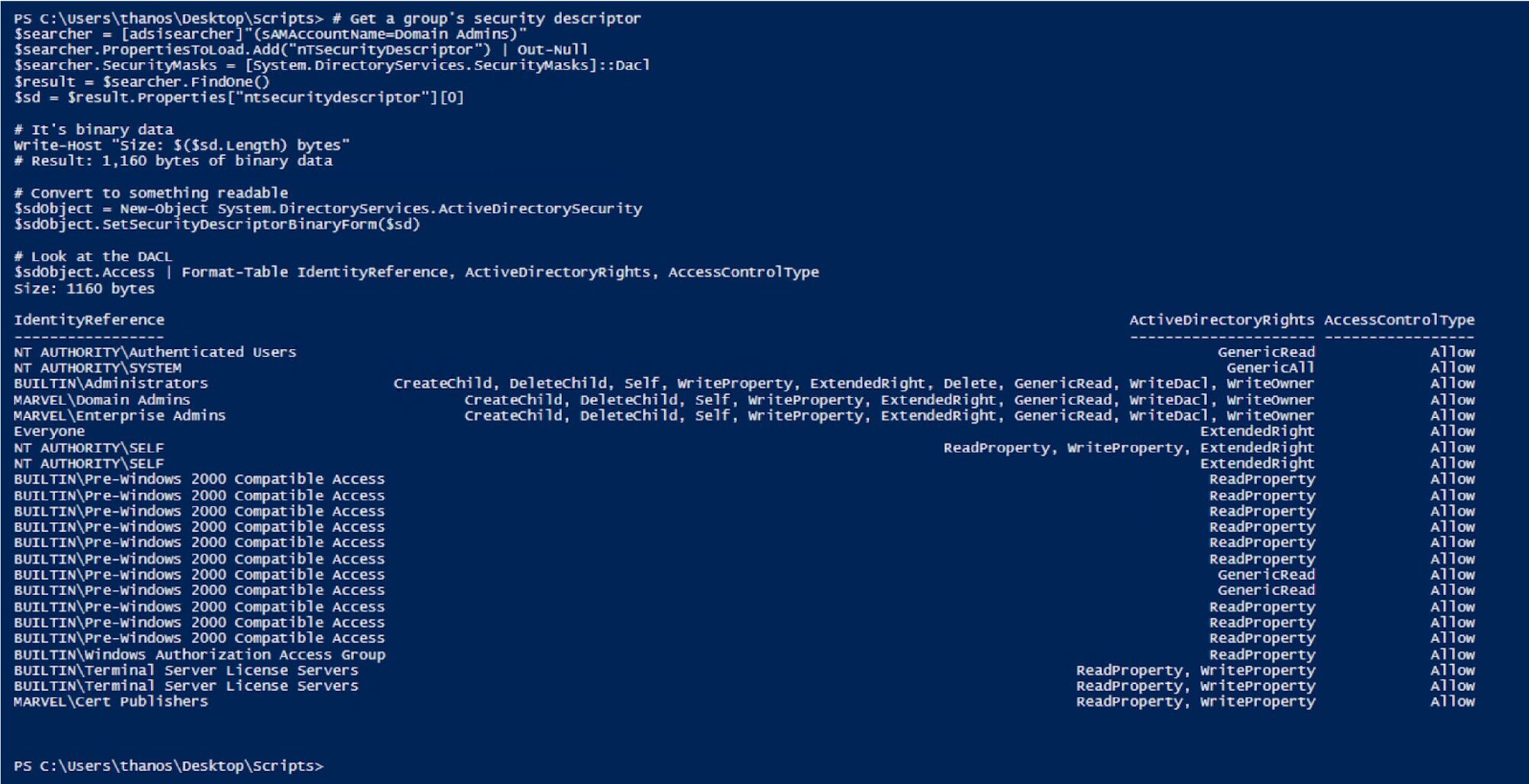

I went back to Microsoft documentation and found MS-DTYP Section 2.4.6: SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR. The structure contains four components: OwnerSid, GroupSid, DACL (Discretionary Access Control List), and SACL (System Access Control List).

I needed to see this in action. Lab time:

My lab Domain Admins group had standard, expected permissions - System, Administrators, Domain Admins, and Enterprise Admins with GenericAll, plus some well-known SIDs with ReadProperty.

But here's what hit me: I could see the permissions.

nTSecurityDescriptor contains:

-

Who has access (IdentityReference)

-

What they can do (ActiveDirectoryRights)

-

Whether it's allowed or denied (AccessControlType)

In my lab, everything was configured correctly. But in a production environment with years of changes, manual modifications, and inherited permissions? You might find:

-

Help Desk with WriteProperty on Domain Admins (can add members)

-

A regular user account that owns a privileged group (can modify permissions)

-

Service accounts with GenericAll on administrative groups

-

Contractors with extended rights they shouldn't have

This is what attack path tools need to discover. Without querying nTSecurityDescriptor, you can't see these permission relationships. You'd know:

-

What groups exist

-

Who is a member of what

-

But NOT who has permissions to modify those groups

That last piece - the permissions data - is what makes attack path discovery possible.

The "aha!" moment: This is how BloodHound works

I immediately thought about BloodHound. I'd run it in my lab before and it showed me attack paths. But I never really understood HOW it found those paths.

Now it made sense.

What BloodHound needs to find attack paths:

-

Who are the users? (basic LDAP query)

-

What groups exist? (basic LDAP query)

-

Who is a member of what? (member attribute)

-

WHO HAS PERMISSIONS ON WHAT? - This is nTSecurityDescriptor!

Without nTSecurityDescriptor, you can't see:

-

That a help desk group can modify privileged groups

-

That User X owns Group Y (and owner can always modify permissions)

-

That a service account has GenericAll on administrative objects

-

That seemingly unrelated users have password reset rights

This is THE critical piece of attack path discovery. You need the permission relationships, not just the membership relationships.

I went back and looked at SharpHound queries in my logs. Every single one requested nTSecurityDescriptor.

SharpHound DCOnly collection:

Attributes: nTSecurityDescriptor, sAMAccountName, objectSid, ...

SDFlags: 0x4

SharpHound group enumeration:

Attributes: nTSecurityDescriptor, sAMAccountName, objectSid, member, ...

SDFlags: 0x5

SharpHound cert template enumeration:

Attributes: nTSecurityDescriptor, distinguishedName, name, ...

SDFlags: 0x5

They ALL query nTSecurityDescriptor. Because without it, you can't map who has the ability to compromise what.

Understanding SDFlags: Why different values?

Now that I understood what nTSecurityDescriptor was, I had another question: Why does SDFlags appear at all? And why do the values differ?

After watching SharpHound in action, the pattern was clear: whenever it requested nTSecurityDescriptor, it used the SDFlags control. The Microsoft documentation says SDFlags lets you specify which security descriptor components to retrieve: Owner, Group, DACL, or SACL.

I looked through my logs and found two distinct patterns:

Pattern 1: SDFlags=0x4 (DACL-only)

When I saw it:

-

General user enumeration

-

Computer object queries

-

Domain object enumeration

-

Trust relationship queries

What they're asking: "Who has permissions on these objects?"

Example from logs:

Filter: (samAccountType=805306368) # Computer accounts

Attributes: nTSecurityDescriptor, sAMAccountName, dNSHostName, ...

SDFlags: 0x4

For computers, ownership doesn't usually matter for attack paths. You just need to know "does anyone have GenericAll or AllExtendedRights?"

Pattern 2: SDFlags=0x5 (Owner + DACL)

When I saw it:

-

Group enumeration (100% of the time!)

-

Certificate template queries (100% of the time!)

-

High-value object enumeration

What they're asking: "Who has permissions on these objects AND who owns them?"

Example from logs:

Filter: (|(sAMAccountType=268435456)(sAMAccountType=268435457)...) # Security groups

Attributes: nTSecurityDescriptor, sAMAccountName, objectSid, member, ...

SDFlags: 0x5

This makes sense when you think about attack paths. In a misconfigured environment, you might find something like this:

Group: "Domain Admins"

Members: captain, thor, thanos

DACL (what SDFlags=0x4 shows):

- "Help Desk" has WriteProperty (can add members)

Owner (what SDFlags=0x5 additionally shows):

- "loki" (regular user!) owns the group

Attack paths:

-

Path 1: Anyone in Help Desk can add themselves to Domain Admins

-

Path 2: loki owns group, modifies DACL, grants self WriteProperty, adds to Domain Admins

Without the Owner information (0x5 includes it, 0x4 doesn't), you'd miss Path 2 completely!

This is why SharpHound uses 0x5 for groups. Ownership of groups is a critical attack path that's often misconfigured.

Whether SDFlags is used for performance, convention, or just how the developer wrote the code doesn't really matter for detection purposes. What matters is the pattern:

-

Legitimate admin tools: Query nTSecurityDescriptor WITHOUT SDFlags

-

SharpHound: ALWAYS uses SDFlags when querying nTSecurityDescriptor

That difference makes it detectable.

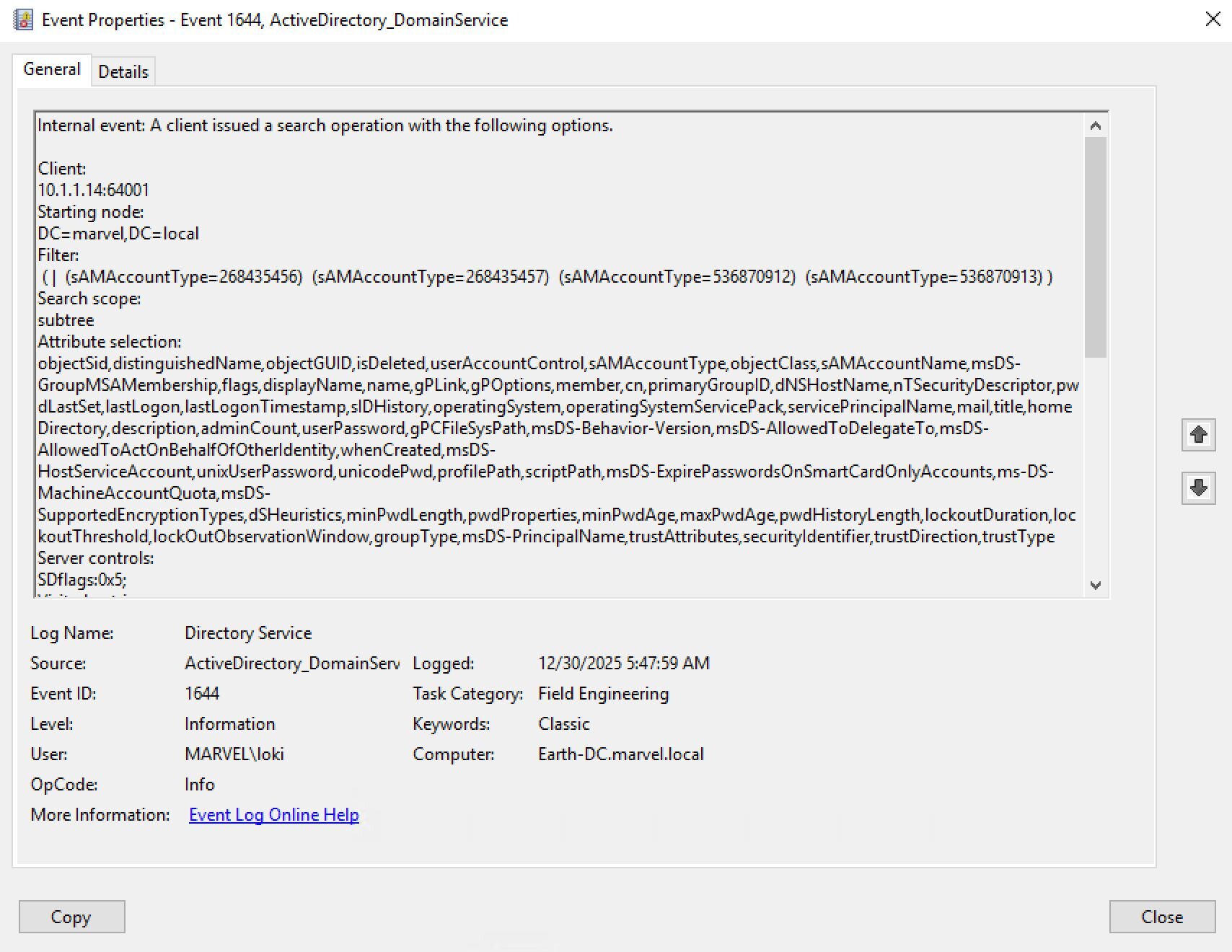

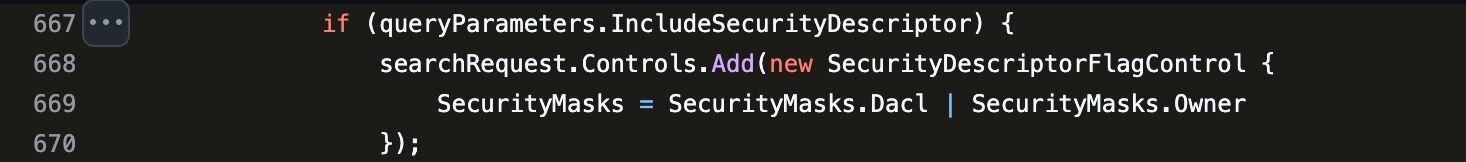

Confirming in the source code

Nasreddine Bencherchali reviewed the SharpHound source code and found exactly where SDFlags is implemented, sending me the relevant links to confirm what I was seeing in the logs.

The flag is set in SharpHoundCommon's LdapConnectionPool.cs. In my testing, different Collection Methods produced different values: 0x4 for general enumeration and 0x5 for groups.

Figure 3: LdapConnectionPool.cs showing SDFlags set to Dacl | Owner (0x5) when requesting security descriptors.

In my testing, different Collection Methods produced different values: 0x4 for general enumeration and 0x5 for groups.

The detection opportunity

After finally noticing SDFlags and understanding what it meant, I realized I'd been walking past a near-perfect detection signature.

SDFlags usage is extremely rare in legitimate operations.

I checked our environment:

-

Legitimate admin tools: Rarely use SDFlags in my testing (they query specific objects, not mass enumeration)

-

Backup software: Doesn't use SDFlags (doesn't need permission data)

-

Monitoring tools: Don't use SDFlags (don't need security descriptors)

The only things I found using SDFlags:

-

SharpHound (attack path tool)

-

My own testing (after learning about it)

That's it.

The detection pattern:

Mass LDAP enumeration (100+ objects)

+ nTSecurityDescriptor attribute

+ SDFlags control (0x4 or 0x5)

= Attack path discovery in progress

|

Tool |

Filter Pattern |

SDFlags |

Attributes |

|

SharpHound |

Group sAMAccountType |

0x5 |

nTSecurityDescriptor, member, ... |

|

Custom Scripts |

Varies |

Rare |

Varies |

|

Legitimate Admins |

Specific DN |

Typically none |

Basic attributes |

Even better, I could differentiate tools: the combination of SDFlags=0x5 + group enumeration is HIGHLY specific to BloodHound/SharpHound.

Validating the pattern

To confirm this, I ran SharpHound in my lab with different collection methods:

Test 1: DCOnly (SharpHound.exe -c DCOnly):

Event 1644 logs showed:

-

Multiple queries with SDFlags: 0x4 (users, computers, domains)

-

Multiple queries with SDFlags: 0x5 (groups, cert templates)

-

ALL queries requested nTSecurityDescriptor

Test 2: Group Collection (SharpHound.exe -c Group):

Event 1644 logs showed:

-

Consistent SDFlags: 0x5 for ALL group queries

-

Filter: (|(sAMAccountType=268435456)(sAMAccountType=268435457)...)

-

Always included nTSecurityDescriptor

Test 3: Comparing to legitimate admin activity

I asked our AD admins to perform common tasks while I monitored Event 1644:

Legitimate activity:

Admin using ADUC to check "Domain Admins" members:

Filter: (distinguishedName=CN=Domain Admins,CN=Users,DC=corp,DC=local)

Attributes: member, description

SDFlags: [None]

Admin using PowerShell to get group members:

Filter: (sAMAccountName=Server Admins)

Attributes: member, sAMAccountName

SDFlags: [None]

SharpHound activity:

SharpHound group enumeration:

Filter: (|(sAMAccountType=268435456)(sAMAccountType=268435457)...)

Attributes: nTSecurityDescriptor, member, sAMAccountName, objectSid

SDFlags: 0x5

Returned: 847 groups

The difference is obvious:

-

Legitimate: Specific DN, basic attributes, no SDFlags

-

Attack tool: Mass enumeration, security attributes, SDFlags present

Building detection rules

After understanding what SDFlags means and confirming the pattern, I built detection rules based on this investigation.

In my testing, SharpHound consistently used SDFlags 0x4 and 0x5. Other attack path tools may use different values, which we'll explore in Part 4.

Note: The following are detection logic excerpts showing the key selection criteria. Field names use Elastic Common Schema (ECS). Adjust for your SIEM. The Source filter matches remote IP:port connections, filtering out local DC operations.

SharpHound group enumeration (SDFlags 0x5):

detection:

selection_base:

event.code: 1644

selection_filter_samtypes:

winlog.event_data.LDAPFilter|contains|all:

- '(sAMAccountType=268435456)'

- '(sAMAccountType=268435457)'

- '(sAMAccountType=536870912)'

- '(sAMAccountType=536870913)'

selection_scope_subtree:

winlog.event_data.SearchScope: 'subtree'

selection_sdflags_owner_dacl:

winlog.event_data.SearchFlags:

- 'SDflags:0x5;'

selection_src:

winlog.event_data.Source|re: '^(\d{1,3}\.){3}\d{1,3}:\d{1,5}$'

condition: selection_base and selection_filter_samtypes and selection_scope_subtree and selection_sdflags_owner_dacl and selection_src

Key takeaways

-

Sometimes the most valuable signals are the ones you're not looking at yet. I was so focused on filters and attributes that SDFlags didn't register until one day it finally did.

-

nTSecurityDescriptor is THE critical piece for attack path discovery. Without it, tools like BloodHound can't work. This makes it a reliable detection point.

- SDFlags reveals intent. The combination tells the story:

- One object + nTSecurityDescriptor = Admin checking permissions

-

Mass objects + nTSecurityDescriptor + SDFlags = Attack path discovery

-

Owner information matters for groups. SDFlags=0x5 (vs 0x4) specifically requests Owner data, which is why SharpHound uses it for group enumeration. Group ownership is often misconfigured and creates attack paths.

-

Legitimate admins don't use SDFlags. In our production monitoring, only SharpHound and security research tools used it. Baseline your environment before deploying.

Conclusion: Pay attention to what you're ignoring

I'd been looking at Event 1644 logs for weeks. Analyzing filters, tracking attributes, and building detection rules. And the whole time, SDFlags was right there in the logs. I just wasn't seeing it.

The day I finally noticed that field, everything changed. What started as "Wait, what is that?" became:

-

Understanding how nTSecurityDescriptor works

-

Realizing this is THE foundation of attack path discovery

-

Recognizing the detection opportunity in SDFlags

-

Building high-confidence detection rules

-

Finding a pattern that only appears during attack path enumeration

This is what detection engineering actually looks like: Not just analyzing what you're focused on, but occasionally stepping back and asking, "What else is in these logs that I'm not paying attention to?"

The next time you're deep in an investigation, take a moment to look at the fields you've been skipping over. You might find the detection opportunity you didn't know you were looking for.

Thanks to Jonathan Johnson, Charlie Clark, Anton Ovrutsky, Matt Anderson, Tyler Bohlmann, Lindsey O'Donnell-Welch, Michael Haag, Nasreddine Bencherchali, and Adam Bienvenu for their help in reviewing this post.