Summary

In early February 2026, Huntress responded to an intrusion where threat actors leveraged compromised SonicWall SSLVPN credentials to gain initial access to a victim network. Once inside, the attacker deployed an EDR killer that abuses a legitimate Guidance Software (EnCase) forensic driver with a revoked certificate to terminate security processes from kernel mode, a technique known as Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver (BYOVD).

The attack was disrupted before ransomware deployment, but the case highlights a growing trend: threat actors weaponizing signed, legitimate drivers to blind endpoint security. The EnCase driver's certificate expired in 2010 and was subsequently revoked, yet Windows still loads it, a gap in Driver Signature Enforcement that attackers continue to exploit.

Technical analysis

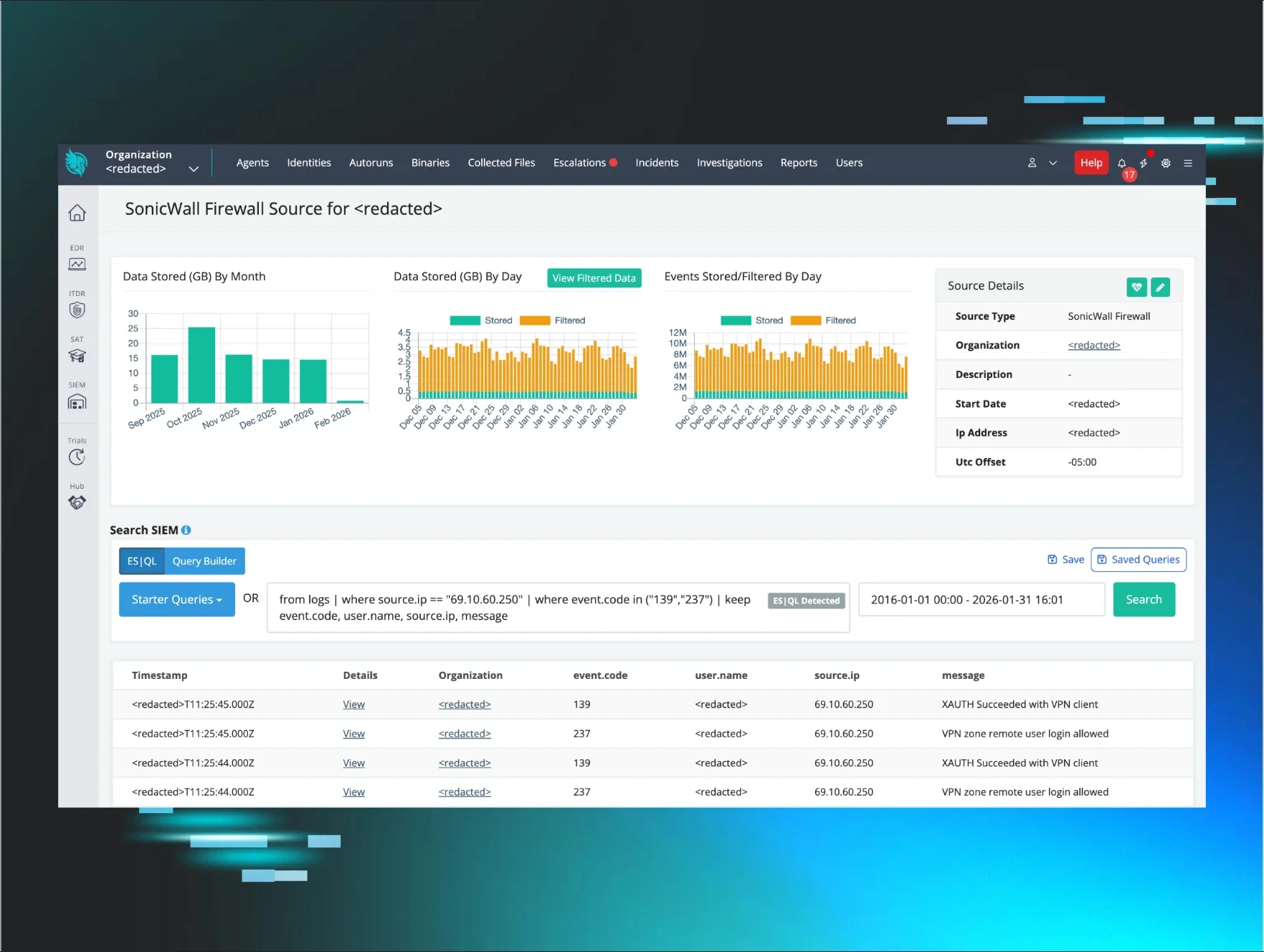

Huntress Managed SIEM ingested SonicWall telemetry from the victim environment, which proved critical in detecting and piecing together the intrusion timeline. Analysis of VPN authentication logs revealed the threat actor successfully authenticated to the SonicWall SSLVPN from a malicious external IP address in February 2026.

Notably, the logs also captured a denied portal login attempt from 193.160.216[.]221 just one minute prior; the account lacked privileges for portal access from that location. The attacker then successfully authenticated via VPN client from a different IP 69.10.60[.]250.

Figure 1: Huntress SIEM dashboard showing successful authentication events from threat actor’s IP

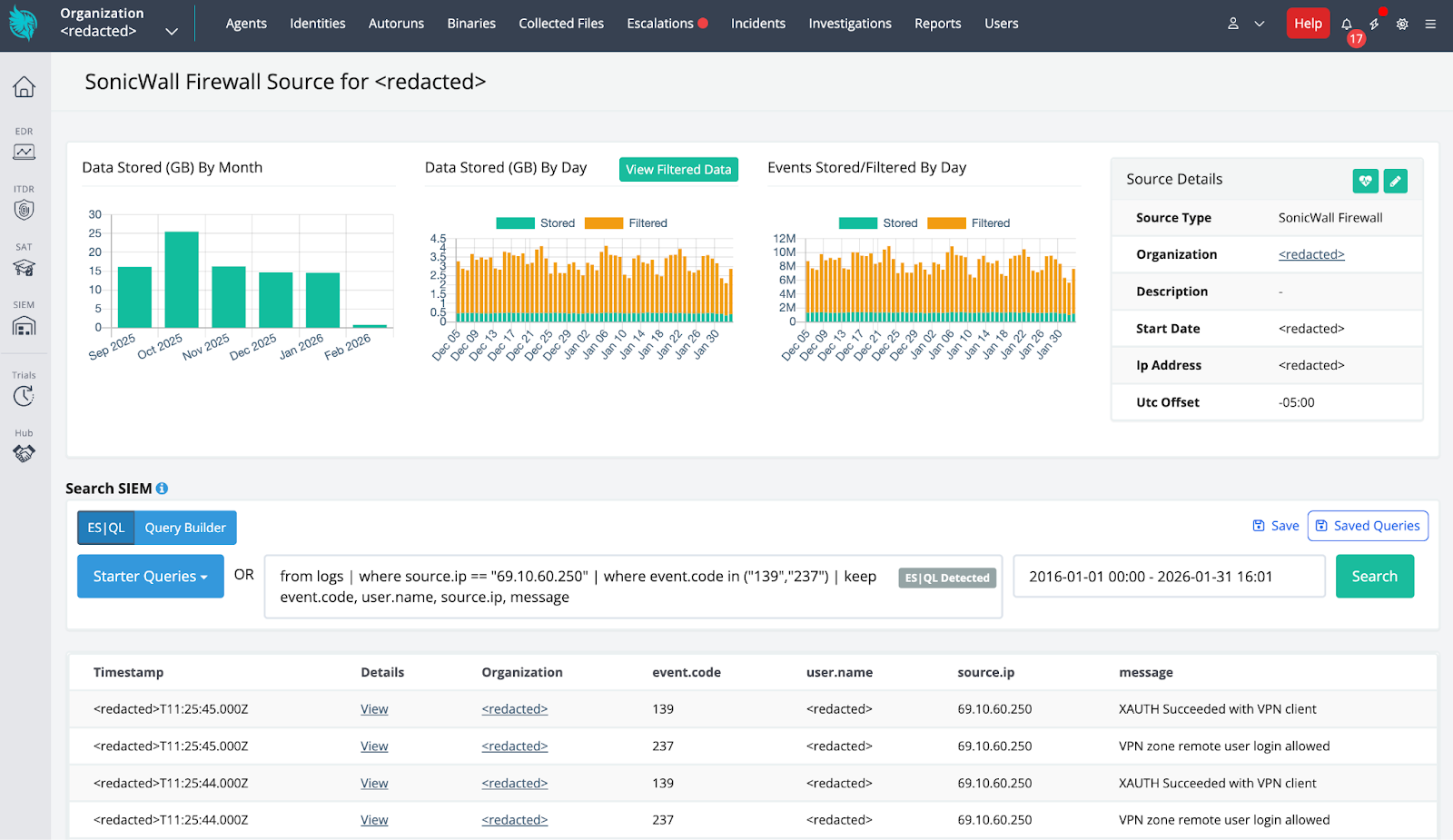

Correlation between SIEM telemetry and endpoint visibility allowed Huntress to quickly identify the threat, quarantine affected systems, and provide the client with actionable remediation recommendations.

Figure 2: SIEM correlation with EDR detection

Discovery

Once authenticated, the threat actor conducted aggressive network reconnaissance. SonicWall IPS alerts captured ICMP ping sweeps, NetBIOS name request probes, and SMB-targeted activity, including SYN flood behavior at rates exceeding 370 SYNs/second.

Execution

EDR killer

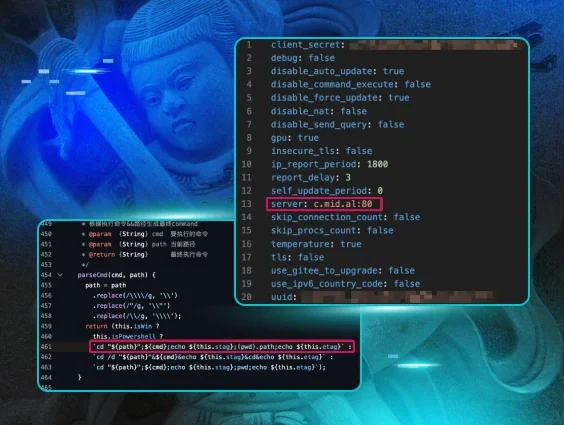

The binary is a 64-bit Windows executable that deploys a kernel driver to terminate security software processes. It masquerades as a legitimate firmware update utility.

Embedded BYOVD

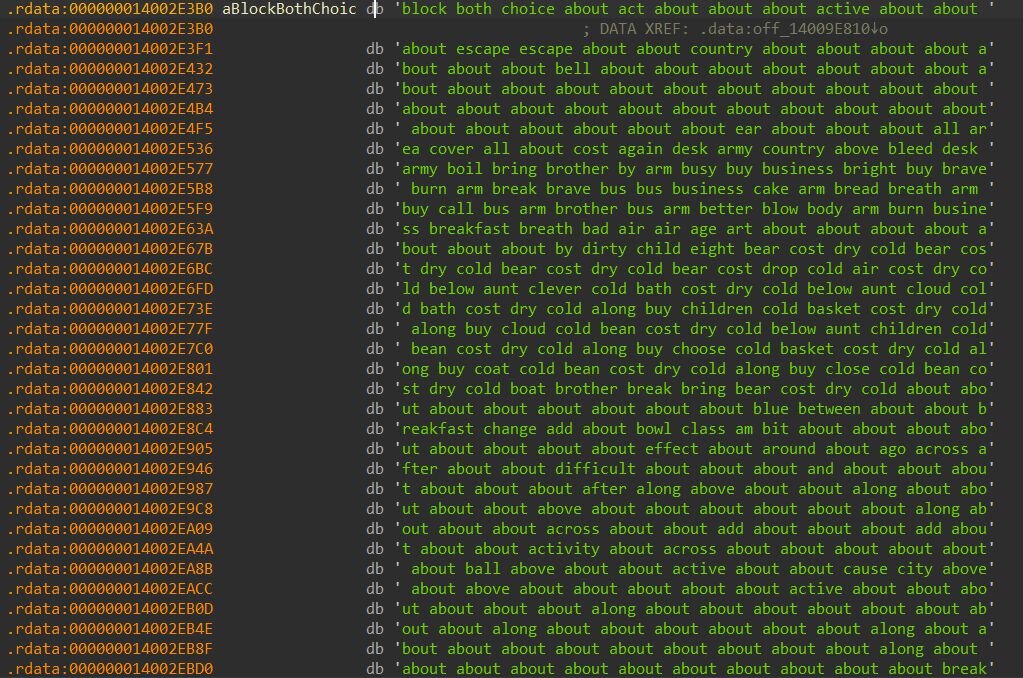

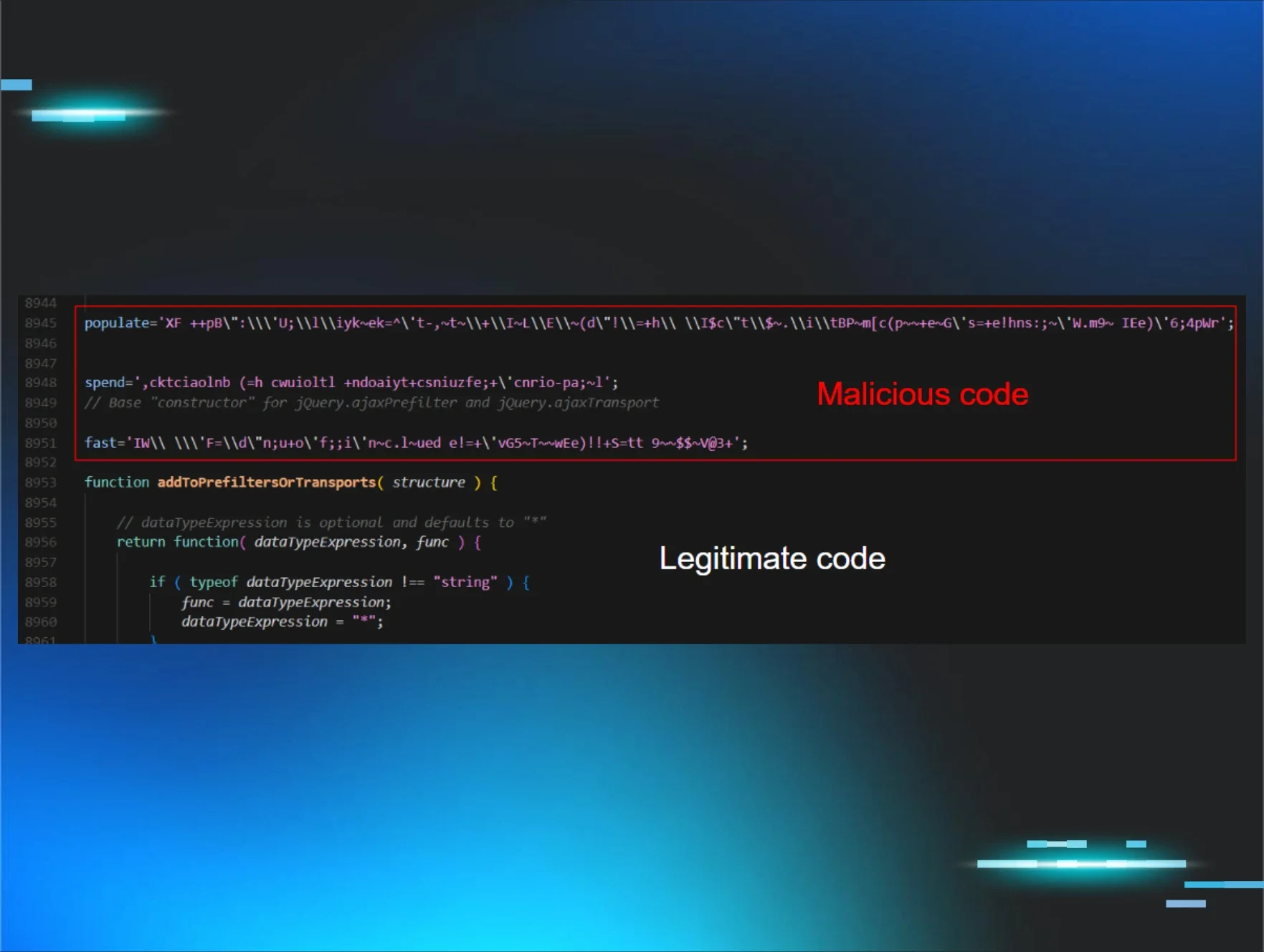

The EDR killer binary leverages a custom encoding scheme to conceal its embedded kernel driver payload. Rather than storing the driver as raw bytes or using traditional encryption, the malware developers opted for a wordlist-based substitution cipher that transforms each byte of the driver into an English word. This technique is particularly effective at evading static analysis tools, as the encoded payload appears to be nothing more than innocuous English text scattered throughout the binary's data section.

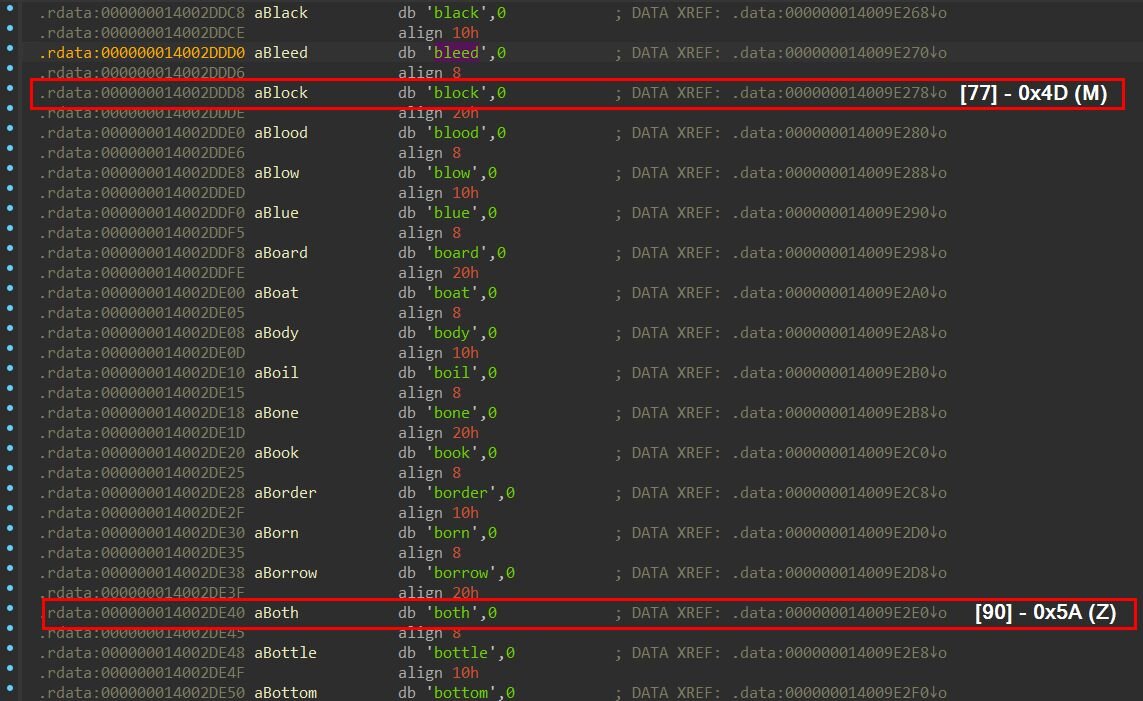

At the heart of this encoding scheme lies a 256-word dictionary embedded within the binary. Each word in this dictionary corresponds to a specific byte value; the word's index in the array equals the byte it represents. For example, "about" sits at index 0 and decodes to 0x00, “block” at index 77 decodes to 0x4D (the ASCII value for “M”), and “both” at index 90 decodes to 0x5A (ASCII “Z”). The encoded driver payload itself is stored as a 384,528-byte string of space-separated English words. When decoded, these words translate back into the original kernel driver.

Figure 4: Wordlist-encoded driver payload

The decoding routine implements a straightforward lookup algorithm. It initializes a string parser to tokenize the encoded blob word by word, then iterates through each extracted word. For every word encountered, the function performs a linear search through the 256-entry wordlist, comparing the current word against each dictionary entry until it finds a match. Once matched, the word's index becomes the decoded byte value, which is appended to an output buffer.

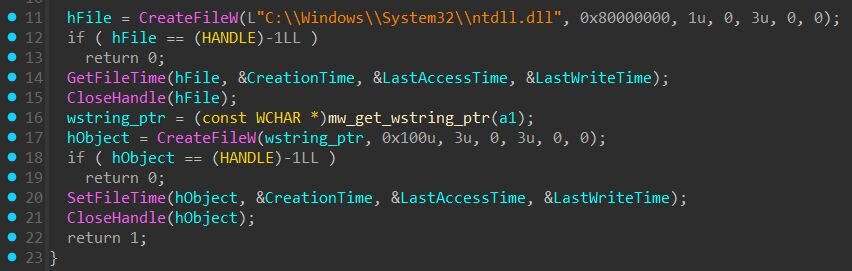

The first few words of the encoded payload demonstrate this transformation clearly: "block both choice about" decodes to “4D 5A 90 00”, the infamous MZ signature of a DOS executable header. This confirms the decoded output is a valid Windows PE file. The decoded driver is then written to “C:\ProgramData\OEM\Firmware\OemHwUpd.sys”, after which the binary applies anti-forensic measures: setting the file attributes to hidden and system to conceal it from casual directory browsing, and copying timestamps from the legitimate ntdll.dll to make the malicious driver blend in with system files.

Figure 5: Timestomping: The binary copies timestamps from ntdll.dll to the dropped driver to blend in with legitimate system files

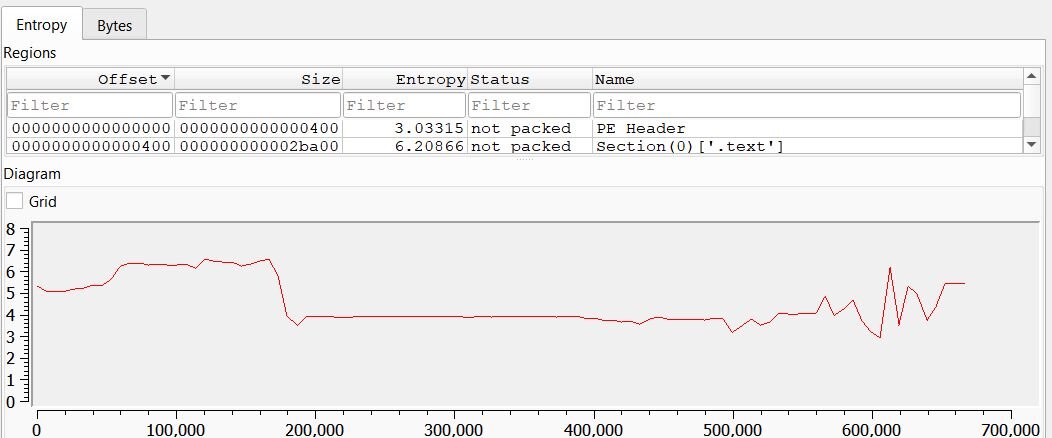

This encoding approach offers several advantages for the attacker. Traditional string-based detection fails because the payload contains no suspicious API names, file paths, or binary signatures in its encoded form. Entropy-based analysis designed to detect packed or encrypted malware can be ineffective here; the wordlist-encoded payload registers around 4 bits/byte, well below the 7-8 bits/byte threshold that typically flags suspicious encrypted or compressed content.

Figure 6: Entropy of the svchost.exe binary (Source: DiE)

Target identification

The binary maintains a list of 59 target process names that are hashed at initialization using FNV-1a (seed 0x811C9DC5). During runtime, it enumerates running processes via CreateToolhelp32Snapshot, converts each name to lowercase, computes its FNV-1a hash, and compares against the pre-computed target hashes. This allows fast integer comparison rather than 59 string comparisons per process.

The kill loop runs continuously with a 1-second sleep interval, ensuring any security process that restarts is immediately terminated again.

The EDR killer targets 59 processes spanning major endpoint security vendors:

Notably absent from the kill list? Huntress. While the EDR killer targets nearly every major EDR and AV vendor on the market, the Huntress agent was not among the 59 processes targeted for termination.

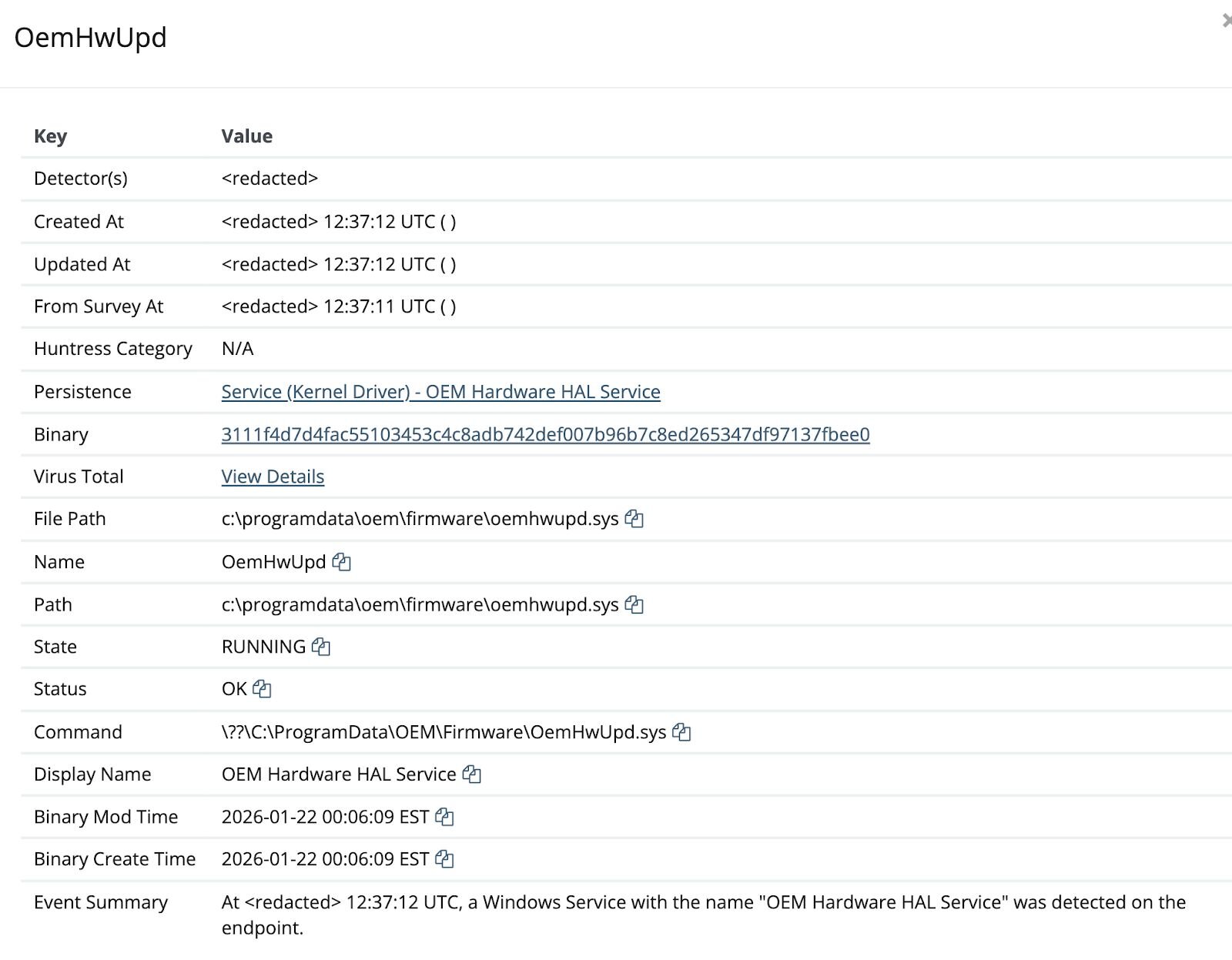

Persistence

Once the kernel driver is decoded and written to disk, the binary establishes persistence by registering it as a Windows kernel service. This allows the driver to be loaded into the kernel and survive system reboots.

The binary first checks if a service with the same name already exists; if so, it deletes the old service before creating a new one. It then registers the driver with the Service Control Manager using carefully chosen names designed to blend in with legitimate OEM software:

Service Name: OemHwUpd

Display Name: OEM Hardware HAL Service

Description: Manages hardware abstraction layer compatibility

Binary Path: C:\ProgramData\OEM\Firmware\OemHwUpd.sys

Service Type: Kernel Driver

Start Type: Demand Start

Driver Signature Enforcement

Since Windows Vista x64, Microsoft has required all kernel-mode drivers to be digitally signed by a trusted Certificate Authority. This policy, known as Driver Signature Enforcement (DSE), prevents unsigned or tampered drivers from loading into the kernel. When a driver is loaded, Windows verifies that the digital signature is cryptographically valid and chains back to a Microsoft-trusted root certificate.

However, there's a critical gap in this verification process: the kernel does not check Certificate Revocation Lists (CRLs). While Windows can verify that a signature is mathematically valid and was issued by a trusted authority, it cannot determine whether that certificate has since been revoked by the issuing CA. This limitation exists for practical reasons: drivers load early in the boot process before network services are available, and CRL checks would significantly impact boot performance. Even when a CRL is manually imported into local certificate storage, the kernel bypasses this check entirely.

The EnCase driver exploited in this attack perfectly illustrates this gap. Its signing certificate expired in January 2010 and was subsequently revoked, yet Windows still accepts the signature because the cryptographic verification succeeds. From the kernel's perspective, the signature remains valid.

Microsoft's blocklist approach

Rather than implementing CRL checking, Microsoft introduced the Vulnerable Driver Blocklist, a hash-based deny list that prevents specific known-bad drivers from loading. Since the Windows 11 22H2 update, this blocklist is enabled by default when Hypervisor-Protected Code Integrity (HVCI) or Memory Integrity is active. The blocklist is updated with each major Windows release, typically once or twice per year.

This approach offers precision that certificate revocation cannot: blocking individual driver hashes avoids the collateral damage of revoking an entire certificate, which could break legitimate software from the same vendor. However, it's inherently reactive; a driver must first be identified as vulnerable, reported to Microsoft, and added to the blocklist before protection takes effect.

The certificate for the “EnPortv.sys” driver that the TA deployed has been expired for over 15 years and was subsequently revoked, yet Windows accepts it because the kernel only validates the cryptographic chain, not expiration or revocation status.

Once loaded, the driver exposes an IOCTL interface that allows usermode processes to terminate arbitrary processes directly from kernel mode. This bypasses all usermode protections, including Protected Process Light (PPL) that typically guards critical system processes and EDR agents.

Despite the invalid certificate status, Windows loads this driver because:

-

The July 29, 2015, exception: Starting with Windows 10 version 1607, Microsoft required all new kernel drivers to be signed via the Hardware Dev Center. However, to maintain backward compatibility, Microsoft created an exception: drivers signed with certificates issued before July 29, 2015, that chain to a supported cross-signed CA are still permitted to load. The EnCase driver's certificate was issued on December 15, 2006, well before this cutoff.

-

Valid timestamp: The driver contains a timestamp from Thawte Timestamping CA (a VeriSign service). When code is signed with a timestamp, Windows validates the signature against the time the signature was created, not the current date. Because the driver was timestamped while the certificate was still valid (before January 31, 2010), the signature remains valid indefinitely, even though the certificate has since expired.

-

Trusted certificate chain: The signature chains through VeriSign Class 3 Code Signing 2004 CA to Microsoft Code Verification Root, which Windows trusts for kernel-mode code signing.

Once loaded, the driver exposes an IOCTL interface that allows usermode processes to terminate arbitrary processes directly from kernel mode. This bypasses all usermode protections, including Protected Process Light (PPL) that typically guards critical system processes and EDR agents.

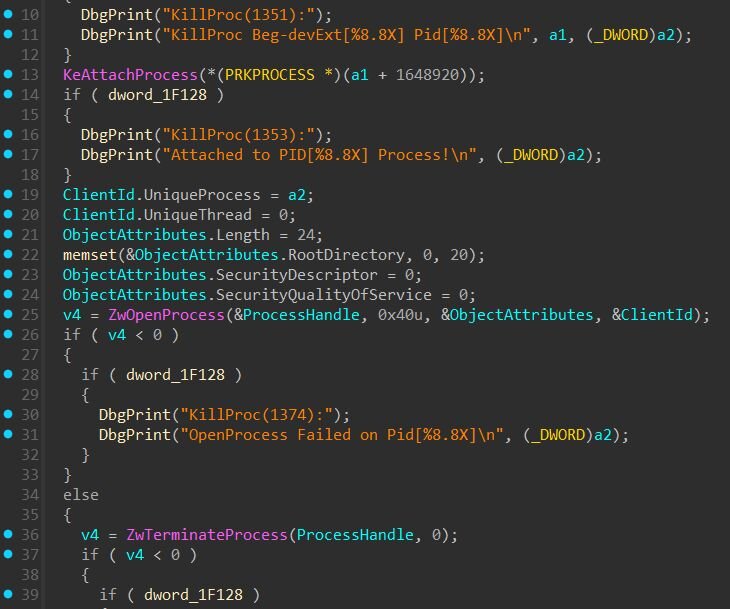

The EnCase forensic driver (EnPortv.sys) exposes 18+ IOCTL functions designed for forensic acquisition, including process termination (KillProc), DKOM process hiding (HideProc/UnhideProc), kernel-mode file deletion (DeleteFile), physical memory access (OpenPhysicalMemory/ReadPhysicalMemory), process memory reading (PidMemory), and VAD enumeration (GetVadList).

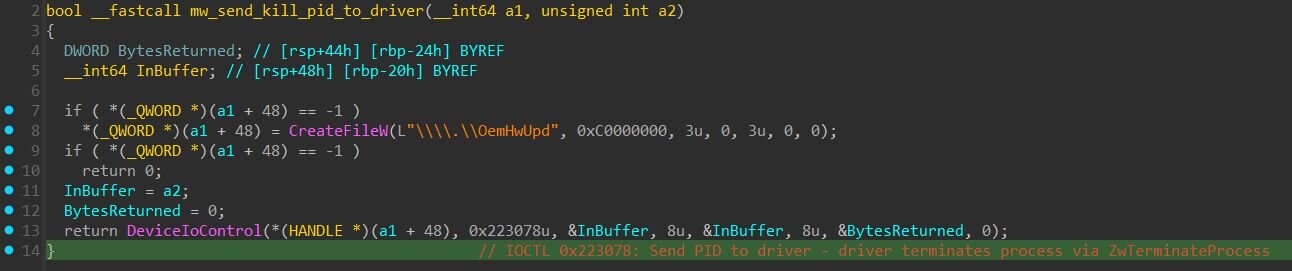

Out of all these capabilities, the threat actors in this incident only used IOCTL 0x223078 (KillProc) to terminate EDR processes. The usermode component opens a handle to the driver's device (\\.\OemHwUpd) and sends target PIDs via DeviceIoControl. The driver, executing in kernel mode, calls ZwOpenProcess with PROCESS_TERMINATE access followed by ZwTerminateProcess. When kernel-mode code calls Zw* functions, the wrapper sets PreviousMode to KernelMode, signaling that parameters come from a trusted source, Windows skips the security validation it would enforce on usermode callers.

Figure 8: Usermode component sending target PID to kernel driver via IOCTL 0x223078 (Source: svchost.exe)

Figure 9: KillProc implementation (from driver)

Conclusion

This intrusion demonstrates how BYOVD attacks have become a standard component of the modern ransomware playbook. By repurposing a legitimate forensic tool signed over 15 years ago, threat actors can bypass Driver Signature Enforcement, and gain kernel-level capabilities to terminate any security process on the system.

The attack chain with compromised VPN credentials, EDR killer deployment follows a well-established pattern seen in ransomware precursor activity.

Recommendation

- Enable MFA on all remote access services - the initial compromise was possible because the SonicWall SSLVPN account lacked multi-factor authentication

- Review VPN authentication logs for anomalous login patterns and denied access attempts preceding successful authentication

- Enable HVCI / Memory Integrity - ensures Microsoft's Vulnerable Driver Blocklist is enforced

- Alert and monitor services with names mimicking OEM/hardware components created outside normal software deployment

- Deploy Microsoft's recommended driver block rules via WDAC to block known vulnerable drivers

- Enable ASR rule "Block abuse of exploited vulnerable signed drivers" to prevent applications from writing vulnerable drivers to disk

Indicators of compromise

|

Item |

Description |

|

C:\ProgramData\OEM\Firmware\OemHwUpd.sy |

Driver Path |

|

OemHwUpd |

Service Name |

|

OEM Hardware HAL Service |

Service Display Name |

|

69.10.60[.]250 |

Threat actor IP |

|

193.160.216[.]221 |

Threat actor IP |

|

3111f4d7d4fac55103453c4c8adb742def007b96b7c8ed265347df97137fbee0 |

EnCase driver (OemHwUpd.sys) |

|

6a6aaeed4a6bbe82a08d197f5d40c2592a461175f181e0440e0ff45d5fb60939 |

EDR killer binary (svchost.exe) |