Hey, you. I have a question for you. Don’t think too hard before you answer. Ready? Here goes.

Where do identity attacks come from?

Maybe your gut reaction to that question is to answer with a country, state, city, or continent. You’d be right, but only sometimes. In fact, if you only consider the geographical location of an attack as the relevant location, the United States actually accounts for most of the origin points for identity attacks.

Maybe your gut reaction is that they come from VPNs, TOR exit nodes, and proxies. Again, you’d be right, but only sometimes. Later in this post, you’ll see the numbers for how many identity attacks originate from these technologies (spoilers: it’s more than double the rate of geographically relevant origins).

But even if you answer “they sometimes come from locations, like a country or city, and sometimes from a technology, like a VPN” then you are mostly correct but still wrong. This was the exact situation I found myself in at the start of the events that precipitated this blog post.

The point that I’m getting at is that the identity space is multidimensional. If you only consider the two axes of geographical location and technologies like VPNs, you’re playing checkers. The modern identity adversary does not play checkers. They don’t play chess, either. They play Go. If we don’t move fast, our asses get encircled.

Figure 1: The game the identity adversary plays

So to even the playing field, I want to pass along some hard-fought wisdom about where identity attacks truly come from. Let me tell you about one of the hardest lessons that we have learned when trying to define the dimensions of the playing field of identity attacks and how we regained the upper hand. It all starts with a concerning trend that I noticed and a hearty challenge of my previous assumptions.

Co-occurrence & the art of detection negative space

I routinely analyze the Huntress Managed Identity Threat Detection and Response (ITDR) product data as part of my daily duties as a product researcher. I’m responsible for the innovation and efficacy of ITDR, and it’s crucial to follow the product data to answer for both of those responsibilities. It was earlier this year, while running some routine data analyses, that I noticed something quite odd. But I can’t tell you the odd thing just yet. (Stick with me.)

To explain this odd thing, I must first explain the concept of signal co-occurrence. Signal co-occurrence is the term I use to describe when individual detection systems trigger for the same identity at disparate parts of the attack chain. Examining which detectors trigger alongside other detectors, especially when the two detectors aren’t in the same area of the attack chain, can be extremely useful for measuring detection system efficacy.

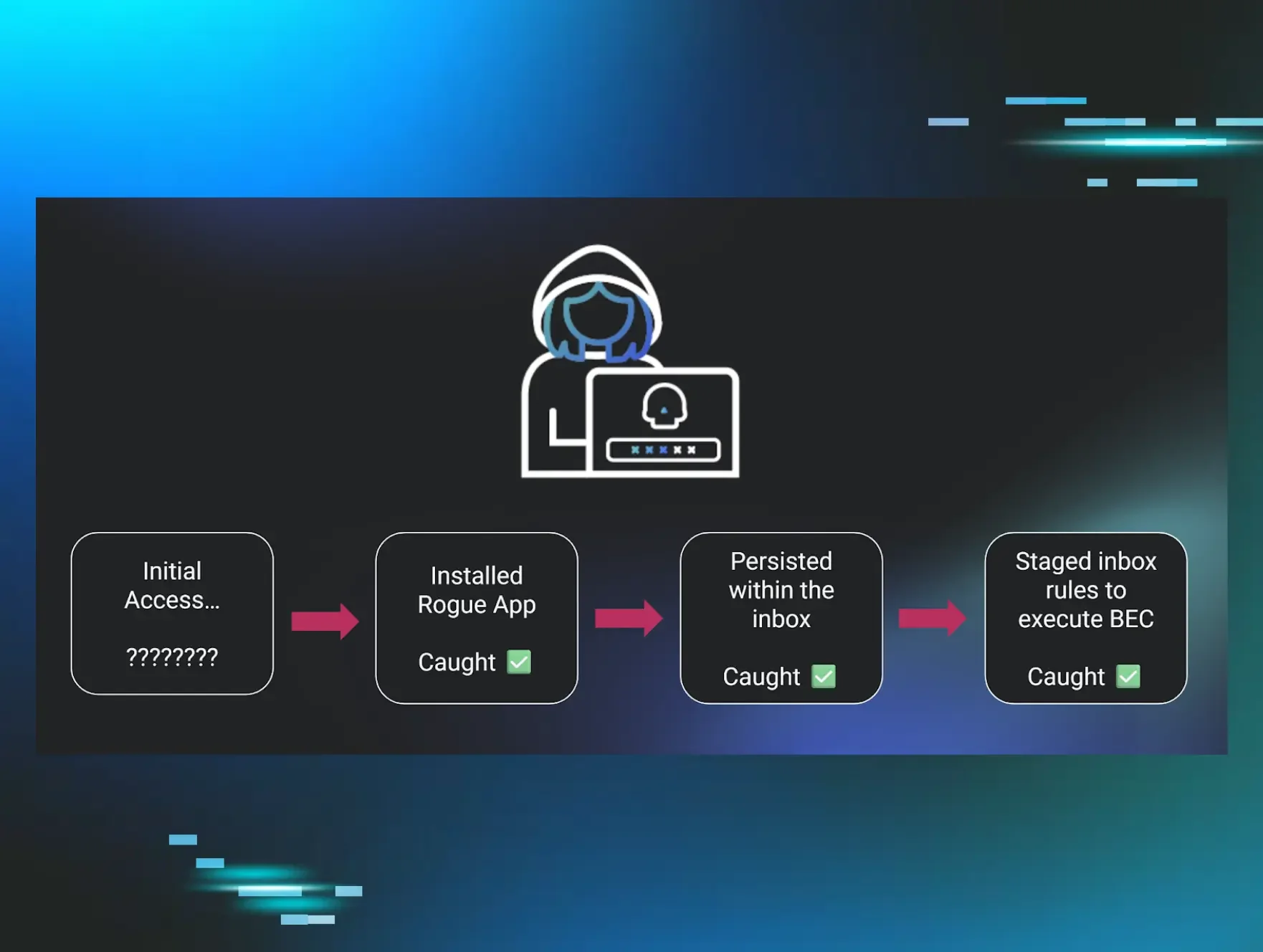

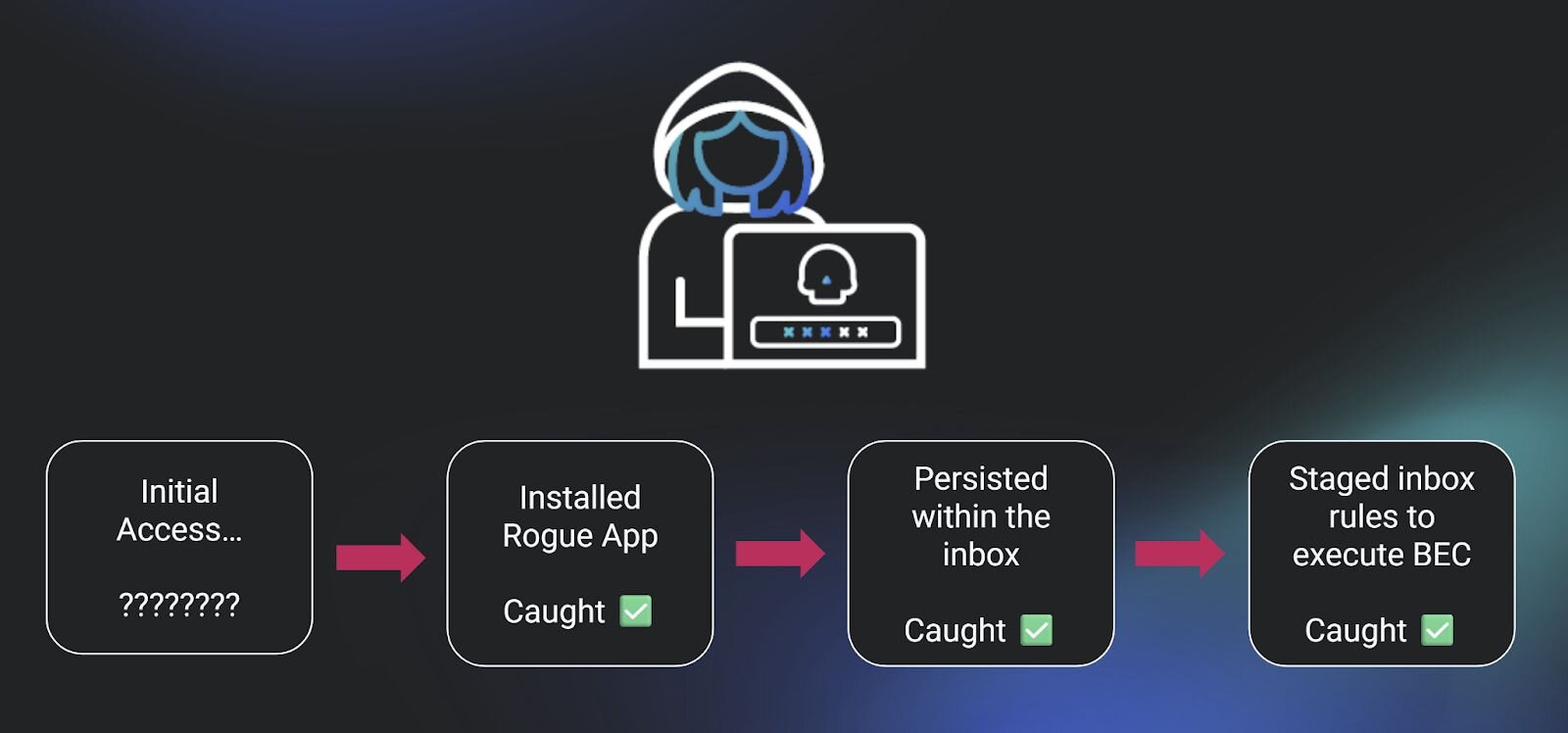

If three alerts trigger for the same identity within the same timeframe across different parts of the attack chain, what’s the outcome? We can reasonably conclude that our detection system works well in layers. An alert for a suspicious login, followed by an alert for the installation of an application, followed by an alert for a suspicious inbox rule, means that the layers that correspond to different parts of the attack chain are working to spotlight each step in an identity attack. This is signal co-occurrence in action.

Figure 2: Representation of three stages of an attack chain, where we alerted for each stage

Studying co-occurrence to determine product efficacy is one use of this concept. But the more interesting use is to determine the negative space of detection. Where does our product fall short in identifying attacker tradecraft? What are we not seeing alongside the confirmed alerts within the same attack?

With the context of negative detection space, the graphic above takes on a totally different meaning. An astute reader may be asking, “Shouldn’t there also be some kind of initial access in the example graphic above?”

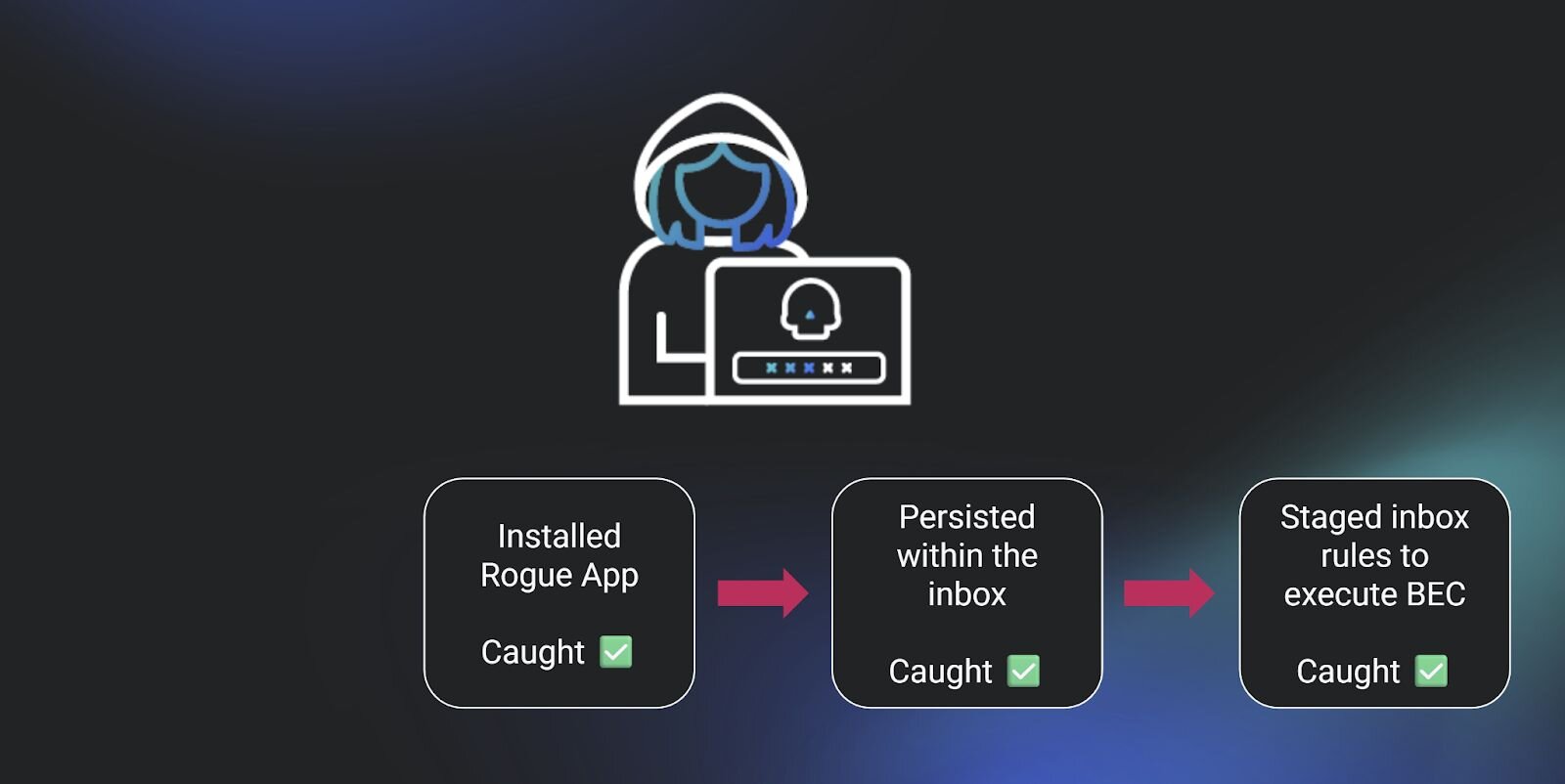

You’re right. See the nice, big empty space to the left of “Installed Rogue App” in that graphic? I think it’s time to explain the “odd thing” I was referring to earlier.

Earlier this year, an increasing number of positive confirmed attacks that were co-occurrent across Huntress-protected identities lacked an initial access alert. We started to see an alarming number of true positive alerts, which included the creation of inbox rules, the installation of a rogue application, the execution of a mass outbound spam attack, and other post-exploitation tradecraft. Each instance of these co-occurrent signals was attributed to one identity, within the same session, in roughly the same timeframe. And for every single one of them, we had no idea how the attacker gained initial access.

Figure 3: Pictured here, my actual nightmare

In all of these examples, we still caught the threat actor during their post-exploitation. Some would say that it only really takes one good alert to stop an attack in progress, so perhaps we could interpret this as a success in spite of missing the initial access method.

Not me.

Figure 4: Me, when this was happening

Yes, I’m glad we caught the threat actor, but I actually interpret this as a detection failure. If you missed the point of initial access in one instance of an attack, you can't assume that was the only instance where you missed it. Your detection system has gaps if you can’t recount the attack chain in each of its phases. Maybe this means attackers are shifting their tradecraft. Maybe this means your detection systems are short on telemetry. It’s hard to tell exactly until you roll up your sleeves and dig into the data.

So earlier this year, I went to work to answer the question: What initial access methods were we missing, and why was our established detection system for initial access failing us?

Location in the identity space

Identity telemetry is scarce. We generally have to go a long way with a little data when it comes to proving malice during identity attacks. And perhaps the best indicator of interest for identity telemetry is the point of origin for identity activity—none other than the IP address. But using IP addresses to prove malice is much more complicated than it would initially seem.

For some background, ITDR was developed to hard-counter initial access tradecraft in the summer of last year when we released our Unwanted Access capability. Unwanted Access directly combats credential theft, session token theft, and other forms of account takeover by analyzing login telemetry. We developed the product to analyze and identify discrepancies for anomalous locations, unexpected VPNs, token reuse, and other forms of initial access.

Crucially, we split the threat model into two distinct areas: location and tunnels. “Location” here means geographical location indicated by an IP address. A login from a residential IP address located in Germany, for example, could be anomalous if the protected identity doesn’t travel often and is located in the United States. This addresses the classic identity detection challenge of identifying anomalous locations and stopping an account takeover when it originates from an unexpected location.

“Tunnels” represents a much more interesting and nuanced detection space. When proxies or VPNs are in use, the notion of geographic location of an IP address essentially goes out the window. This makes sense when you think about it. Assume you observe a login from an IP address based in Germany. If taken at face value, one would be tempted to call this “a login from Germany,” but if that IP address is a registered VPN exit node, can we really say that the user behind that login (malicious or otherwise) is truly “logging in from Germany”? Of course not. Yet that is one of the most common ways that I’ve seen other solutions handle the concept of anomalous logins for identity, and it’s where I see other solutions fail the most.

So right from first principles, we built ITDR to handle the two classes of “location” differently. Is there a VPN or proxy associated with the IP in question? Disregard the location. No VPN or proxy association? Treat the implied geography as relevant. The country, state, region, or continent implied by the IP address for a VPN login event is irrelevant. The relevant fact is the VPN itself, the provider of that VPN, and whether that VPN is routinely used by the identity or not.

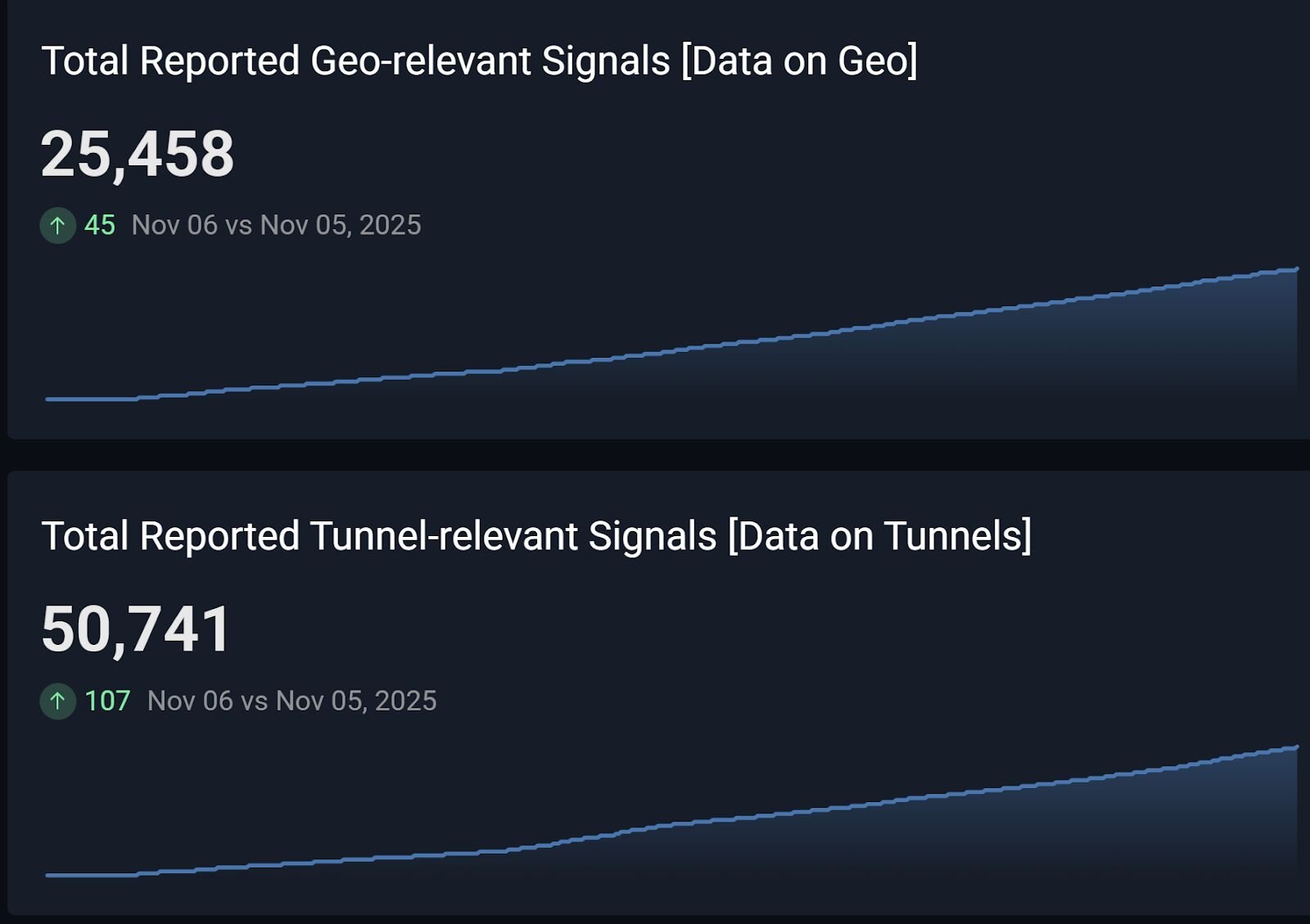

This strategy is far from perfect, but it has proven to be extremely effective. We even see tunnel-related incidents occur at double the rate of geographically relevant IP addresses. If you treat all IP address “locations” by their implied geography, you completely miss this nuance.

Figure 5: We observe and report tunnel-related incidents at roughly twice the rate of geographically relevant incidents

(Side note, forgive the diatribe. This is precisely why “impossible travel” isn’t a sound detection strategy. Approaching detection by measuring implied velocity between two points on Earth misses the nuance of the technologies involved. You can “teleport” from Spain to Suriname at the click of a button if you use a VPN. Much of this “impossible travel” is just a benign attribute of the intricate ways in which authentication occurs in the identity space. Sessions move around a lot. Like, a lot, a lot. I could, and probably will, write an entire other blog post about this topic someday!)

In short, Huntress Managed ITDR was killing it when it came to finding account takeovers when a VPN or proxy was in use and when a VPN or proxy wasn’t in use. So imagine my surprise when we could not account for a concerning number of initial access methods. What was going on?

Not location, not tunnel, but a secret third thing

There is, we eventually discovered, a third type of “location” when it comes to IP addresses and the origin points for account takeovers. And it’s a bit more subtle than the other two.

Our threat intel provider, Spur, tags and labels IP addresses based on their attributes. Their data is our primary mechanism for determining if an IP address is using a proxy, VPN, TOR exit node, or another technology. One such tag is the infrastructure tag. The infrastructure tag is routinely null, but sometimes shows a value like “SATELLITE”, “AIRPLANE-WIFI”, or “MOBILE.” These values represent the kind of infrastructure furnishing the IP space. The ones I just listed are self-explanatory. But there’s one additional infrastructure tag that caught my attention: “DATACENTER”. This, as it turns out, would be the key to unlocking this mystery.

Figure 6: I can hear the hum of progress by looking at this image (Source)

Yes, datacenters. Those citadels of steel and silicon that now power most of the digital world. Datacenter-furnished IP space is nothing new, but the way these IPs present in identity telemetry when you can observe eight million identities in action every day is extremely interesting.

Here’s one such observation: Most VPNs and proxies operate in datacenter IP space. But there are instances of IPs with no associated VPN exit node, proxy exit node, TOR exit node, or any other attribute representing a technology that are tagged as Datacenter IPs. So we have a sort of rectangle/square situation going on where most VPNs and proxies are run on top of datacenter infrastructure, but not all datacenter infrastructure hosts VPNs and proxies exclusively. This makes sense when you think about how Microsoft Azure datacenters do a lot more than just host VPN exit nodes, but many VPN providers probably host their tech in cloud space.

Here’s another observation: much like when a VPN or proxy is in play, the physical location of the datacenter is irrelevant. There are several reasons why this is the case. For one, anyone can spin up cloud infrastructure, authenticate to that cloud host, and then use it as a pivot point while they access identity resources. This could be as simple as using a cloud-based Linux host as a SOCKS proxy pivot or as complicated as Azure Virtual Desktop. Does it matter where the datacenter is physically located? Essentially, no. Similarly to the VPN and proxy paradigm, a login from a datacenter located in the US is not “a login from the US.”

When we stepped back and re-assessed how datacenter infrastructure changes the notion of “location” in the identity space, it became clear that we had missed a serious detection opportunity: datacenter IPs with no additional attributes. In other words, we were already detecting logins from datacenter IP space when the IP in question was also tagged as a VPN or proxy, but failing to identify when the IP in question had no additional attribute.

So this should be a closed case then, right? All authentications from datacenter IP space are anomalous and can be reported, right? This should be an easy gap to close, right??? Right??!!

Not even close.

Ten million authentication events later

The amount of identity telemetry that originates from datacenter infrastructure is mind-boggling.

I’m looking at the dashboard for all Huntress-protected identities right now as I write this. Filtering for the last 14 days of data and only against successful authentication events, there are 10.2 million events to sort through. That is an absurdly large detection surface area to work with. We’ll need to get creative.

Let me illustrate how tricky this detection space can be with an example of a major mistake that I made early on. Last year, I formed a hypothesis that token theft in datacenter IP space would be easy to prove by examining events within the same session where one event originated from datacenter IP space and another event occurred from an IP that was not tagged as a datacenter. This hypothesis works wonders for catching token theft from VPNs, proxies, and anomalous locations, so I imagined it would be equally as effective. This hypothesis led to building a detector that routinely created more than one thousand alerts per day where almost none of them were of value to the SOC. To put that into perspective, the equivalent detectors that identify token theft from anomalous locations and VPNs create a fraction of that alert volume per day and are all routinely true positives.

My hypothesis proved to be useless at surfacing evil, but invaluable at proving that benign events bounce around in datacenter IP space a lot.

So, it’s back to the drawing board.

If analyzing sessions that use datacenter IP space is useless for detection and the geographical location of a datacenter IP is not relevant, is there another way to subdivide this problem space? Yes, there is.

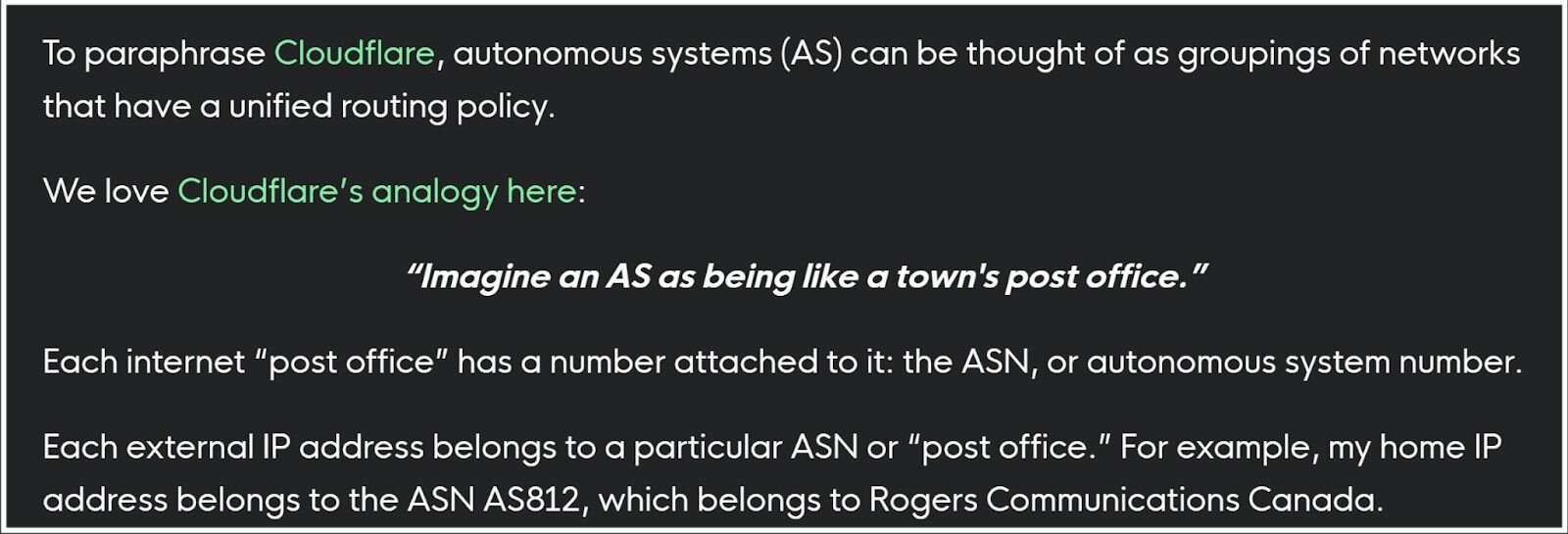

As it turns out, you can’t just build a datacenter and start handing out leased IP space. All IP addresses must be registered and organized under an Autonomous System (AS). My colleagues have written on using AS as a primary threat hunting datapoint, and I can’t think of a way to describe the concept better than they did in that article, so I’ll just post it here!

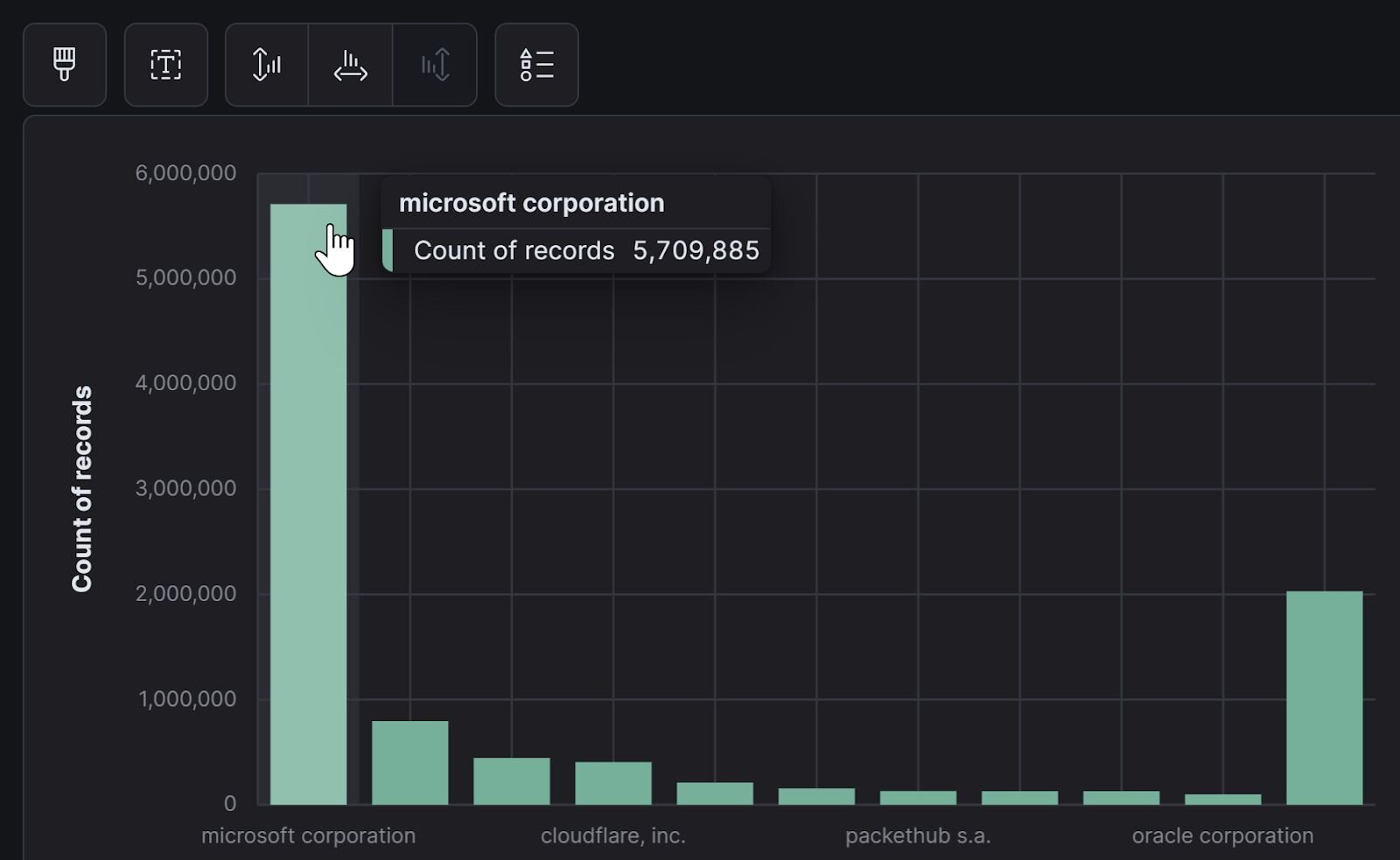

What do the 10 million authentication events look like when grouped by AS? There’s a power law distribution at play where more than half of those events originate from Microsoft datacenters. The remaining top 10 AS organizations are not surprising and include CloudFlare, Google, ZScaler, Amazon, and a few other heavy hitters.

What’s missing from this graph, however, are the names of the insane amount of other Autonomous Systems that exist out in the world. Microsoft has the lion’s share of activity, but there are hundreds upon hundreds of other organizations in this telemetry.

We can subdivide the problem by examining an identity’s events through the lens of their AS organization. This is the cornerstone of our strategy: AS becomes the “country” for a login from a datacenter IP if that IP has no other attribute like a VPN or proxy.

But that’s not the only way to approach the detection problem. Additionally…

Super sus AS

Not all AS are built the same. Microsoft has different payment options, compliance requirements, and business practices than something like “1337 Services GmbH.” Many of these AS lease out IP space and conduct businesses in a way that I’d professionally describe as “sus af bruh.”

One excellent example from my research is Latitude.sh, a bare-metal provider based in Brazil. Latitude leases cloud assets out and accepts anonymous cryptocurrency as payment. This is, of course, attractive for cybercriminals.

We can safely conclude that some AS have a higher potential for abuse and fraud than other AS based on their country of origin, laws in that country, acceptance of cryptocurrency, and other similar factors. It’s not fair to say that all authentication from a provider like Latitude.sh is malicious all of the time, but it’s defensible to describe it as at least worthy of investigation.

With this information in hand, I drafted plans to implement a detection system that classifies identity logins from datacenter infrastructure, compares the events to a baseline of previous datacenter activity, and flags authentication from datacenter IPs that belong to an AS with a higher abuse potential. The Huntress ITDR engineering team and I worked through the summer to bring this system into existence. It went live in August 2025, and here are the outcomes.

The outcomes

By subdividing the problem space, we turned 10 million plus events into a manageable haystack of a few hundred events per day to analyze. To date, we’ve reported over 3,400 instances of datacenter authentication events that met criteria for investigation. Of the 3.4k reports, about 3.2% were rejected. This is a strong performance compared to the baseline of identity detection efficacy, which usually hovers around a 4-5% rejection rate.

Most importantly, this has severely cut down on the number of examples where the ITDR product completely missed the initial access method but later caught post-exploitation tradecraft.

Figure 9: I can sleep at night again. For now.

Conclusion

So…where do identity attacks come from?

If you only interpret “location” to be geographical, you miss a huge part of the overall picture. Even if you interpret location to include the tech that an adversary might use, like a VPN, you’re still missing nuance. Today, we’re seeing hackers move away from VPNs in favor of VPS, where they can rent datacenter IP space that blends in among the deluge of benign datacenter identity activity.

We need to alter our strategy in the defensive space when it comes to the point of origin for identity attacks. “Location” in the identity space includes the geography implied by an IP address, the technology fingerprint of that IP address, and the underlying infrastructure that facilitates the IP address. The way we handle each of those types of “location” makes all the difference when it comes to closing visibility gaps.