Everyone loves a good life hack, right? I’ve found that one such hack for those in cybersecurity is the NIST Cybersecurity Framework.

When the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) first released their cybersecurity framework (now known as the NIST CSF) in 2014, it was looked to as a “gold standard” for how organizations should organize and improve their cybersecurity program. Many choose to emulate the NIST CSF since it’s the simplest one to implement and follow. But don’t let the previous sentence fool you. The NIST CSF is also complex when you really get into the weeds.

While the NIST cybersecurity framework serves several purposes, its primary goal is to reduce cybersecurity risk to an acceptable level for an organization. I’d say the close second is to provide a common language for all organization stakeholders to use to maintain clear and consistent messaging. It keeps everyone aligned and informed on the direction the organization wants to take regarding its cybersecurity posture.

If nothing else, I hope that you finish this blog knowing that it is imperative you implement a framework for guidance and refining the technological stack you’re using.

In addition to having the NIST CSF as a guiding light, it also aids in identifying gaps in your knowledge. We simply don’t know what we don’t know, and often that’s due to not having experienced certain learning opportunities in our day-to-day activities. While the NIST CSF is not a one-size-fits-all framework, it’s meant to provide guidance and complement an existing risk management program—and in the absence of one, the framework should be leveraged to initiate one.

What is the NIST Cybersecurity Framework?

The NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) is a set of guidelines designed to help organizations secure their critical infrastructure and improve their ability to identify, prevent, detect, respond and recover from cyber incidents. Today, it is embraced by many to help manage their organization’s cybersecurity risks and provide a common language to leverage between technical and non-technical teams.

While other standards and guidance have existed for many years, the need to create the NIST CSF specifically came from Executive Order 13636 Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, which was signed in February 2013. Since then, versions 1.0 and 1.1 of the framework have been released, with v1.1 being the most recent which was released in April of 2018. The NIST CSF will likely see an update soon, as they have indicated the goal of updating at least every three years.

So if the framework was created to address critical infrastructure, does that mean all organizations cannot benefit from it? Not at all.

Within the documentation, it clearly calls out the framework can and should be used by any organization in any sector.

“While the Framework has been developed to improve cybersecurity risk management as it relates to critical infrastructure, it can be used by organizations in any sector of the economy or society. It is intended to be useful to companies, government agencies, and not-for-profit organizations regardless of their focus or size.”

Essentially, all organizations should be using it to some extent to help guide them through the process of securing their assets. If I had to elevator pitch the NIST CSF, I’d say it’s a framework that provides a standardized common language for organizations to identify, assess and mitigate cybersecurity risks—resulting in an increased cybersecurity posture. Its value is found in the simplified approach of helping organizations continuously iterate to uncover and address evolving cybersecurity risks.

Want some help evaluating your existing stack against the NIST CSF? Watch our on-demand webinar, Leveraging A Proven Framework to Evolve Your Stack, for some expert insight!

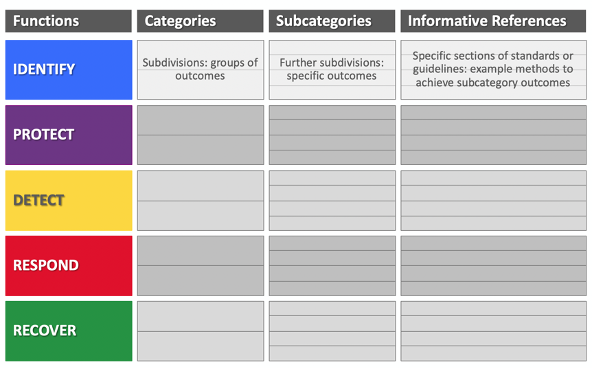

So, what’s in the NIST CSF? It is composed of the Framework Core (Figure 1), which includes the Functions, Categories, Subcategories, and Informative References. For the sake of this blog, we’re going to review the five functions and some of the categories within each function.

Figure 1: Framework Core

Identify (ID)

The Identify (ID) function is critical. Not to say that all functions aren’t of equal importance, but if this one is not executed meticulously, you may fail to provide proper controls throughout the remainder of the CSF. Essentially, you can’t protect what you don’t know exists. This function aims to identify all the “things” in use to run the organization. Here’s how NIST defines the ID function:

“The data, personnel, devices, systems, and facilities that enable the organization to achieve business purposes are identified and managed consistent with their relative importance to organizational objectives and the organization’s risk strategy.”

The list below outlines the Identify function’s categories:

- Asset Management (ID.AM): 6 subcategories

- Business Environment (ID.BE): 5 subcategories

- Governance (ID.GV): 4 subcategories

- Risk Assessment (ID.RA): 6 subcategories

- Risk Management Strategy (ID.RM): 3 subcategories

- Supply Chain Risk Management (ID.SC): 5 subcategories

Let’s take a deeper look at the Asset Management (ID.AM) category. It’s comprised of 6 subcategories, as noted above, and I bet most of you reading this use or administer a tool that can address some of the needs within.

For example, your RMM is exceptionally powerful if you truly harness its functionality and capabilities to their max potential. It can certainly be used to address ID.AM-1 (Inventory physical devices and systems) and ID.AM-2 (Inventory software and applications) for devices where it can run.

Beyond that, the information collected (once verified, of course) can be used to affect and provide valuable information for the decision-making process in the other categories/subcategories. But that will require some deep diving into the CSF for you to determine.

The remainder of Identify is very much focused on governance, risk and supply chain risk management. For those, I recommend reviewing the related informative references outlined within the CSF.

Protect (PR)

The Protect function of the CSF is aimed at the development and implementation of the necessary controls to limit or contain a cyber-related incident. Here is the definition NIST gives us for Protect:

“The Protect Function supports the ability to limit or contain the impact of a potential cybersecurity event.”

Due to the nature of cyber threats today, we tend to see a heavy focus on this area in terms of dollars. This is just a result of the world we live in. Everyone wants to do everything possible to prevent a cyberattack, but the truth is that overspending within this function leaves little to no room for investment within the remaining functions for when a successful cyberattack is carried out.

As an example, if I put 80% of my available budget in Protect, I’m foregoing controls or tools within the other functions that could be of significant benefit to me when an attack is successful.

The list below outlines the PR function’s categories:

- Identity Management, Authentication and Access Control (PR.AC): 7 subcategories

- Awareness and Training (PR.AT): 5 subcategories

- Data Security (PR.DS): 8 subcategories

- Information Protection Processes and Procedures (PR.IP): 12 subcategories

- Maintenance (PR.MA): 2 subcategories

- Protective Technology (PR.PT): 5 subcategories

You are probably familiar with a number of tools and controls within this function. Most of them likely fall into the Awareness & Training (PR.AT) and Protective Technology (PR.PT) categories. Common tools within Protect usually include security awareness training platforms, email security platforms, antivirus, firewalls (IPS and DLP), access controls (physical and logical), least privilege, network segmentation, and this list could run on forever. With such an exhaustive list, it’s easy to see why so much spend goes to this function.

To provide base coverage within this function, you would want the following solutions at the very least: timely patching (cannot stress this enough), next-gen antivirus (NGAV), MFA, least privilege, network segmentation, firewall w/ IPS, email security, and data encryption (at rest and in transit). That’s a lot, I know. To get a better idea of where to focus the efforts, you can use the CIS Controls v8’s Implementation Group 1 (IG1).

Detect (DE)

The purpose of the Detect function is to ensure the timely detection of cybersecurity events. And according to the NIST CSF, Detect is defined as:

“Develop and implement appropriate activities to identify the occurrence of a cybersecurity event.”

It’s important to note that a “cyber event” is not equal to a cyberattack. As the CSF would put it, a cyber event is “a cybersecurity change that may have an impact on organizational operations (including mission, capabilities, or reputation).” For example, an event can be something as simple as failed login attempts or newly discovered (detected) devices/software on the network.

Here’s a view of the main categories in the Detect function:

- Anomalies and Events (DE.AE): 5 subcategories

- Security Continuous Monitoring (DE.CM): 8 subcategories

- Detection Processes (DE.DP): 5 subcategories

This is yet another function where you can likely leverage your RMM, especially for Windows devices. What can you detect with your RMM? For starters, Windows security events are of vital importance for the detection of potential attacks.

My favorite resource for this is Ultimate Windows Security’s security log page. It’s kind of lengthy, so I’ve outlined some events you may want to consider monitoring for if you aren’t already:

Event ID 1102 – Audit log cleared

What better way to cover tracks than to delete the event viewer security logs? Doing so triggers this event.

Event ID 4625 – Logon failure

Everyone loves a brute-force attack, right? Repeated failed logins are an indication that someone, scripted or otherwise, is attempting to brute-force an account (or multiple accounts).

Event ID 4624 – Successful login

This one requires some fine-tuning, but if there are multiple (tens, hundreds, or possibly thousands) of login attempts for a user account and then a successful login, it’s probably a good idea to assume compromise.

Event ID 4720 – User account created

Often, attackers will create a new user account. This is done to either carry out the attack or resell to another attacker for later use (or both).

Event ID 4798 – A user’s local group membership was enumerated

Ever run ‘net user <username>’? That triggers this event. Successful attacks are all about enumeration and finding the next step forward to carry it out.

Event ID 4799 – A security-enabled group membership was enumerated

Running ‘net localgroup <group name>’ triggers this event. As in the previous event ID, enumeration is the name of the game and doing so leaves breadcrumbs that may lead you to an attack in progress.

Beyond that, you can use your RMM to detect newly installed software and/or devices on the network. The former typically requires some advanced reporting allowing you to create queries for software install dates, and the latter can be performed if your RMM has probing functionality. The few I’ve used have such functionality.

Also, within this function you will find tools like SIEM for log collection, intrusion detection systems (host and network) and EDR. It’s clear that all the tools that cover this function’s goals are to detect as much as you can about an environment so that you can respond with the best course of action—which brings us to our next function.

Respond (RS)

From the NIST CSF, “The Respond Function supports the ability to contain the impact of a potential cybersecurity incident. Examples of outcome Categories within this Function include: Response Planning; Communications; Analysis; Mitigation; and Improvements.” Simply put, the Respond function centers around the controls that aid in the response to cyber events.

The list below outlines Respond’s core categories:

- Response Planning (RS.RP): 1 subcategory

- Communications (RS.CO): 5 subcategories

- Analysis (RS.AN): 5 subcategories

- Mitigation (RS.MI): 3 subcategories

- Improvements (RS.IM): 2 subcategories

Believe it or not, a lot of what’s needed to cover this function are administrative controls, such as an incident response (IR) plan. Prior to having an IR plan, you must assemble a team of people that have defined roles and responsibilities, so that when an incident occurs, everyone knows how to respond.

To prepare, performing tabletop exercises can help with ensuring a poised response to an incident. It’s also recommended to have a procedure for security incident reporting. After an incident, you should have a post-incident meeting to determine what went well and where opportunities for improvement exist.

Analysis can be performed by responding to alerts from your other tools. If you’re currently using an EDR, this is likely one of the tools sending you alerts that should then be investigated by a member of your team. Same for other tools like a SIEM, or maybe you have a SOCaaS that responds to alerts they’ve written.

To address mitigation, you should have a tool that can give you a head start, like isolating a device that has an active cyber incident taking place, and then take whatever other actions are necessary to prevent the expansion of an event.

Recover (RC)

The Recover function focuses on recovering from a cyber incident. This one is pretty self-explanatory, but here’s how the NIST CSF defines it:

“Develop and implement appropriate activities to maintain plans for resilience and to restore any capabilities or services that were impaired due to a cybersecurity incident.”

The list below outlines the core categories within this Recover function:

- Recovery Planning (RC.RP): 1 subcategory

- Improvements (RC.IM): 2 subcategories

- Communications (RC.CO): 3 subcategories

First and foremost, a business continuity and disaster recovery plan must be in place. As part of that planning, ensure you’re discussing with your team or clients the devices and data that should be backed up and their prioritization for recovery. Remember, if you have failed to plan, you have planned to fail.

Outside of the administrative controls, your backup solution is by far the most important thing you have that covers some of this function. Ensure that backups are tested at some frequency and not assumed good because your vendor provides an image of a booted device. Essentially, you don’t know the attached storage is recoverable if you don’t test it.

How to Implement the NIST Cybersecurity Framework

I hate to hit you with the “every business’ needs are unique” excuse, but when it comes to thoroughly implementing the NIST CSF for your organization, it’s going to vary based on environment and needs.

However, you should understand that the NIST CSF is a list of activities and desired outcomes and NOT how or what to implement. To really dive in and know where and what to address, you will have to review Framework Implementation Tiers and Framework Profiles, and they will differ for each organization.

According to NIST, Framework Implementation Tiers “provide context on how an organization views cybersecurity risk and the processes in place to manage that risk.” The Framework Profile “represents the outcomes based on business needs that an organization has selected from the Framework Categories and Subcategories.” Let me help simplify all of that.

Framework tiers range from 1 to 4 and have increasing maturity from one to the next. Each tier has a description regarding Risk Management Process, Integrated Risk Management, and External Participation. The tiers are listed below with the first sentence of their definition for each section, but I recommend diving into the CSF documentation for all the fun details.

Tier 1: Partial

- Risk Management Process – Organizational cybersecurity risk management practices are not formalized, and risk is managed in an ad hoc and sometimes reactive manner.

- Integrated Risk Management Program – There is limited awareness of cybersecurity risk at the organizational level.

- External Participation – The organization does not understand its role in the larger ecosystem with respect to either its dependencies or dependents.

Tier 2: Risk Informed

- Risk Management Process – Risk management practices are approved by management but may not be established as organizational-wide policy.

- Integrated Risk Management Program – There is an awareness of cybersecurity risk at the organizational level, but an organization-wide approach to managing cybersecurity risk has not been established.

- External Participation – Generally, the organization understands its role in the larger ecosystem with respect to either its own dependencies or dependents, but not both.

Tier 3: Repeatable

- Risk Management Process – The organization’s risk management practices are formally approved and expressed as policy.

- Integrated Risk Management Program – There is an organization-wide approach to manage cybersecurity risk. Risk-informed policies, processes, and procedures are defined, implemented as intended, and reviewed.

- External Participation - The organization understands its role, dependencies, and dependents in the larger ecosystem and may contribute to the community’s broader understanding of risks.

Tier 4: Adaptive

- Risk Management Process – The organization adapts its cybersecurity practices based on previous and current cybersecurity activities, including lessons learned and predictive indicators.

- Integrated Risk Management Program – There is an organization-wide approach to managing cybersecurity risk that uses risk-informed policies, processes, and procedures to address potential cybersecurity events.

- External Participation - The organization understands its role, dependencies, and dependents in the larger ecosystem and contributes to the community’s broader understanding of risks.

If I were in a position responsible for implementing all of this, I would use the CIS Controls v8 in conjunction with the NIST CSF. Why CIS Controls? Because it currently maps to the functions of Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond and Recover. It’s also an informative reference for many of the NIST CSF subcategories, so it offers ample coverage across the NIST CSF. CIS Controls incorporates what they call Implementation Groups (IG) which guide to what extent safeguards (controls) are implemented.

Lastly, regardless of the path chosen, reducing cyber risk is a marathon and not a sprint. There’s a plethora of free guidance on how to achieve this, but it’s up to you to determine what is right for your organization based on real discussions about your cyber risk reduction. All the controls provide an opportunity to reduce your risk, but your acceptable level of risk must be determined before you know what to implement beyond the basics.